'Getting Naked' Helps Water Fleas Ditch Pesky Parasites

A tarantula rests on its back in a nest of webbing, its legs periodically flexing. With excruciating slowness, the legs start to extend as a shiny bulge begins to erupt out of the spider's back. Eventually, the tarantula pushes away its old exoskeleton like a dirty pair of pants.

This molting process is one of the most dangerous moments in any arachnid's life, and the same goes for other exoskeleton-adorned creatures, such as crustaceans and insects. But now, research finds that this vulnerable period may actually protect molting animals from parasites.

"Molting shortly after exposure to parasites can actually help hosts get rid of attached parasites before they penetrate the host body," said study author David Duneau, a postdoctoral researcher at Cornell University who completed the research while at the University of Basel, Switzerland. "Therefore, the study suggests a new means for avoiding infection for hosts which molt throughout their lives, like is the case for crustaceans, arachnids, nematodes, amphibians and reptiles." [Skin Shedders: A Gallery of Creatures That Molt]

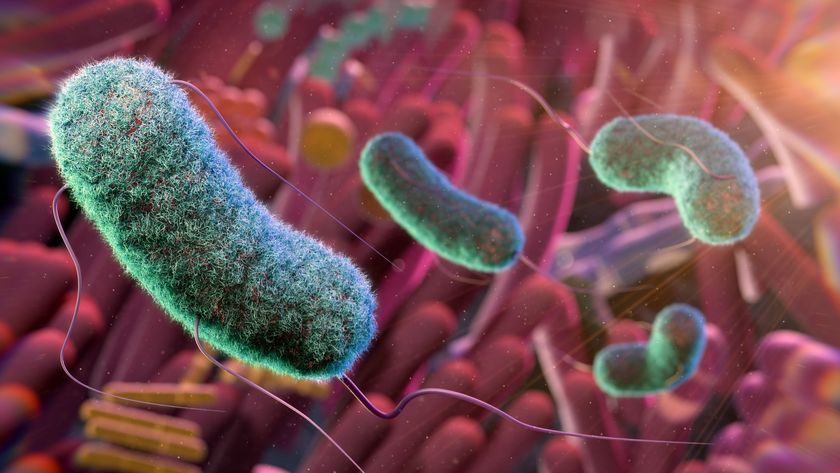

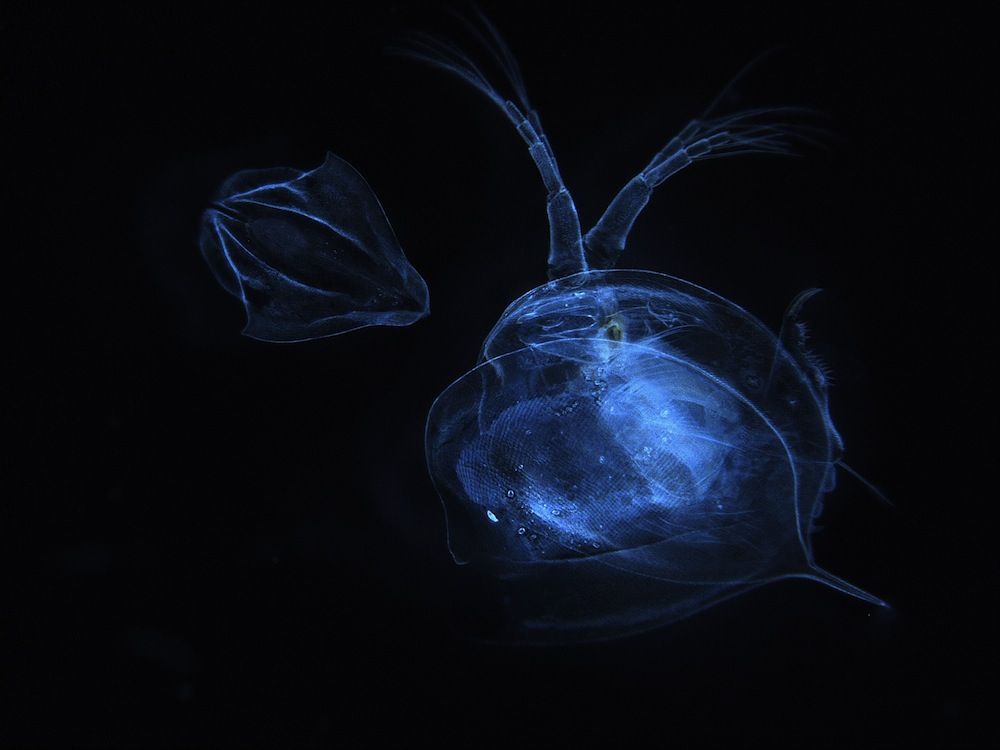

To test this idea, Duneau exposed tiny crustaceans called water fleas (Daphnia magna) to a bacterial parasite in the genus Pasteuria. He then monitored the water fleas for molting and infection rates.

The findings revealed that the water fleas were significantly less likely to be infected by the parasite if they molted within 12 hours of exposure. The findings have several implications, Duneau reported today (April 10) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B. First, parasites are probably under pressure to infect their host soon after attaching, lest they be shed with the molt.

Second, the water fleas didn't seem to be able to start a molt in response to parasites attaching to them; but molting is an energetically intensive process, and so other factors limit when and if they can molt, Duneau told LiveScience. If a host is in a situation where nutrition is limited or it otherwise cannot molt often, those environmental factors could increase the likelihood of a successful parasite infection. Parasites themselves can influence a host's development, Duneau said, potentially influencing molting.

The study might also explain why lizards and snakes are less susceptible to tick-transmitted Lyme disease than birds and mammals (including humans), Duneau said. The Borrelia bacteria that cause Lyme disease need 78 hours of tick-feeding time to travel to the host's body. When reptiles shed their skin entirely, they may disrupt this process, protecting the animal from infection.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.