Are 4 Big Earthquakes in 2 Days Connected?

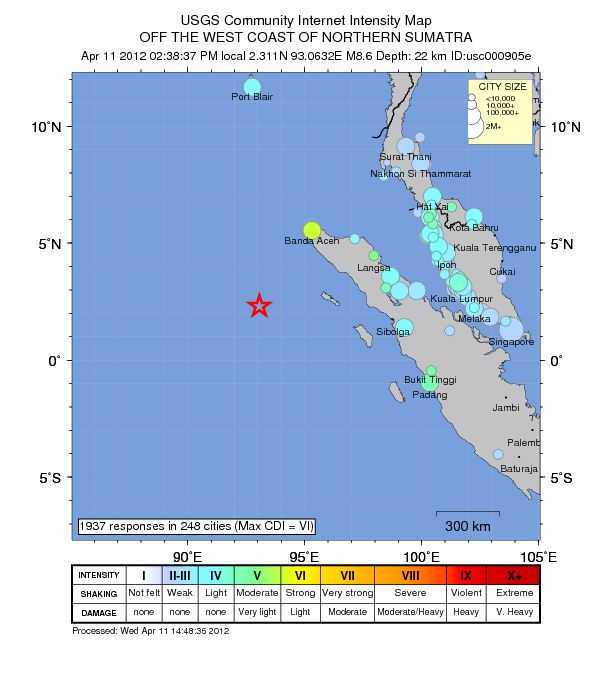

The 8.6-magnitude earthquake that hit off the coast of Sumatra, Indonesia, yesterday (April 11) was followed by several decent-size shakes along the west coast of North America, but researchers can't say for certain whether all the temblors were related.

It's possible, geophysicists say, that quakes off the coast of Oregon, Michoacan, Mexico, and in the Gulf of California ranging from magnitudes 5.9 to 6.9 had something to do with the large earthquake that struck near Indonesia. But the west coast quakes were fairly standard for their location.

"The Earth is in constant motion," said Aaron Velasco, a geophysicist at the University of Texas, El Paso. "I wouldn't necessarily say it's unusual, but we will definitely be looking at these earthquakes to see if there's any link between them."

It's undeniable that earthquakes can trigger other quakes at close range over a short period of time, phenomena known as aftershocks. At a distance, though, the picture is murkier. Quakes can trigger other quakes in two ways, said John Vidale, a seismologist at the University of Washington. First, they can put stress on nearby faults, deforming the crust and making another rupture more likely. That mechanism is limited to regions close to the original quake.

But earthquakes also send surface waves over long distances. The shaking from yesterday's Sumatra quake, for example, was picked up by seismic monitoring stations in the United States. The shaking may not deform the crust, but researchers leave open the possibility that it could still jump-start small quakes. [See a movie of the Sumatra quake shaking the U.S. Midwest]

"My guess is that the shaking was strong enough to actually trigger a little bit of activity," Vidale told LiveScience. But if the west coast activity of the last few days was related to the Sumatra quake, it wasn't out of the ordinary, he added.

"The activity it triggered isn't that much more than was already there," Vidale said. "It doesn't add much to the overall danger."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Proving that two earthquakes are linked over long distances or more than a couple of hours of time is "one of the toughest challenges we face," Velasco told LiveScience. With the earthquake records that are available, it hasn't yet been possible to find any firm patterns, he said.

"We don't have enough data to say yes, and we don't have enough data to say no," he said.

Prognosticating quakes is difficult, because humans don't live on the geologic time scale, said G. Randy Keller, a geophysicist at the University of Oklahoma.

"We only have recorded earthquakes for about 100 years, scientifically," Keller told LiveScience. What that means, he said, is that "if you get somebody who tells you he's got it all figured out, don't believe him."

What researchers do know is that the Sumatra quake was interesting on its own. The quake was a strike-slip quake, meaning the fault moved horizontally, not vertically like the enormous 2004 earthquake that triggered the devastating Indian Ocean tsunami. [Waves of Destruction: History's Biggest Tsunamis]

"This particular earthquake is the biggest strike-slip earthquake that we've seen anywhere, and people are trying to figure out how much motion was on the fault," Vidale said. Either the fault went deeper or was under more strain than seismologists had realized, he said.

"It's too soon to say exactly what we'll learn," Vidale said. "So far, we're just surprised."

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.