Rare Photo: Auroras on Uranus Spotted by Hubble Telescope

Astronomers have caught the first views of auroras on the planet Uranus from a telescope near Earth, revealing tantalizing views of the tilted giant planet's hard-to-catch light shows.

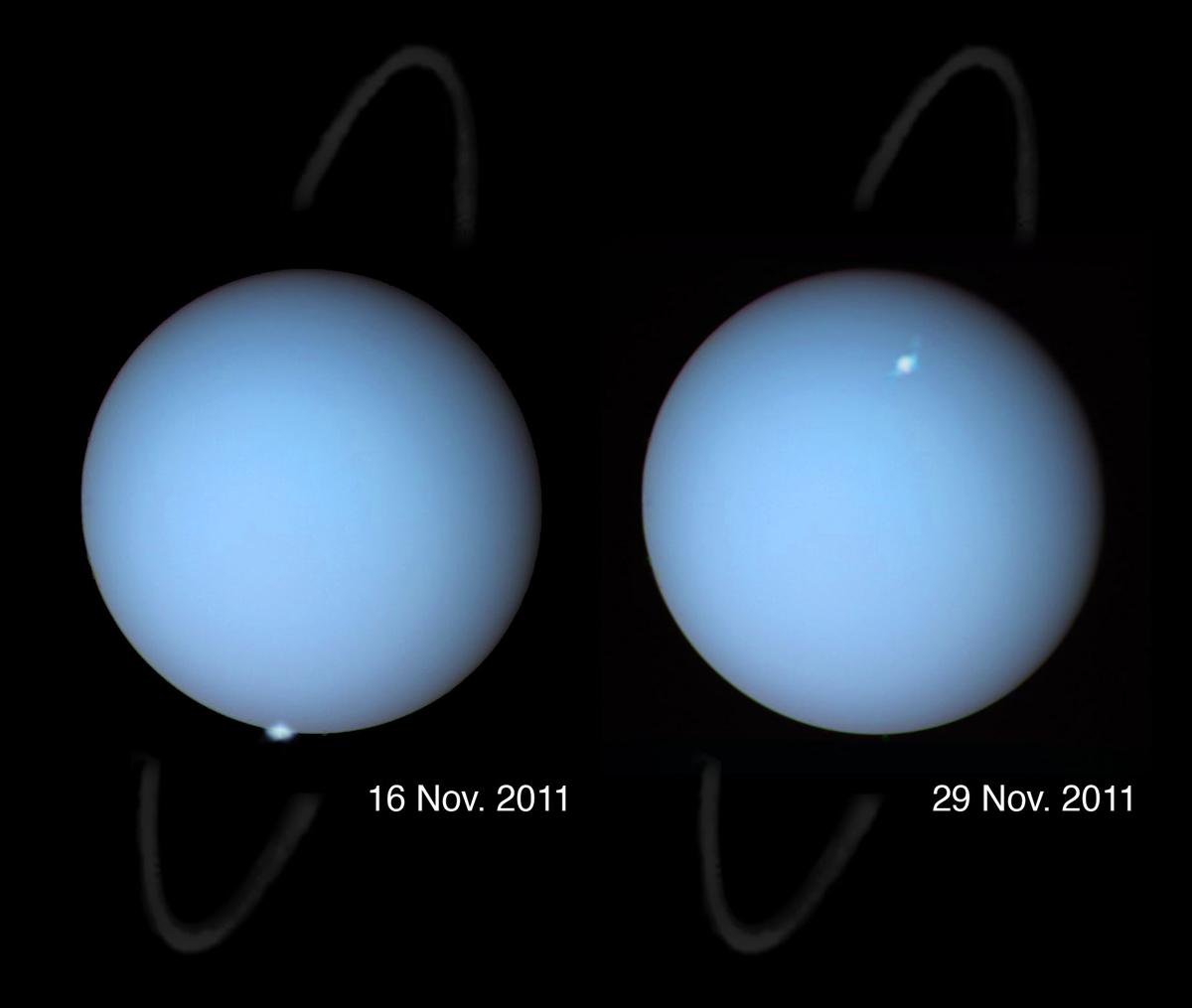

The Uranus aurora photos were captured by the Hubble Space Telescope, marking the first time the icy blue planet's light show has been seen by an observatory near Earth. Until now, the only views of auroras on Uranus were from the NASA Voyager probe that zipped by the planet in 1986.

Snapping the new photos was no easy feat: Hubble recorded auroras on the day side of Uranus only twice, both times in 2011, while the planet was 2.5 billion miles (4 billion kilometers) from Earth. The observation time had to be carefully timed with a passing solar storm to maximize Hubble's chance of seeing auroras on the planet, researchers said.

Auroras are created by the interplay between the magnetic field of a planet and charged particles from the sun's solar wind. The magnetosphere funnels the particles down to the planet's upper atmosphere, where interactions between the atmosphere and solar particles cause a visible glow. On Earth, auroras occur at the north and south magnetic poles, so the light displays are known as the northern or southern lights.

Uranus auroras in action

The last glimpse of Uranus auroras came from NASA's Voyager 2 spacecraft when it flew by the planet more than 25 years ago.

That Voyager 2 flyby showed that Uranus was a "strange beast," said planetary scientist Fran Bagenal of the University of Colorado in Boulder, Colo., in a statement. "We've been really keen to get a better view. This was a very clever way of looking at that." [Photos: Uranus, the Tilted Planet]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To snap the views, astronomers tracked a series of major solar eruptions in mid-September 2011 and calculated the time it would take them to reach Uranus. The charged particles from the solar storm passed Jupiter in about two weeks, but it wasn't until mid-November that they arrived at Uranus, researchers said. By then, the scientists had reserved time on the Hubble Space Telescope to gaze at Uranus and hope for auroras.

"This planet was only investigated in detail once, during the Voyager flyby, dating from 1986," said the study leader Laurent Lamy, with the Observatoire de Paris in Meudon, France, in a statement. "Since then, we've had no opportunities to get new observations of this very unusual magnetosphere."

Earth's northern lights can last for hours and dazzle skywatchers with colorful displays, but the Uranus auroras lasted only a few minutes. Even then, the events were just faint glowing dots above the planet's atmosphere. Hubble spotted the light shows at locations that corresponded to the northern magnetic pole of Uranus, researchers said, which would make them the Uranian northern lights.

Light show on a tilted planet

While auroras have been seen on other planets in our solar system, such as Jupiter and Saturn, Uranus is unique because of its extreme tilt, which scientists think was created by a collision with another planet-size object.

Uranus rotates on an axis tilted so far over that the world is essentially spinning on its side. The magnetic field of Uranus is also tilted at a 60-degree angle from the rotational axis. For comparison, Earth's magnetic axis is only tilted about 11 degrees from its rotational axis.

Because of Uranus's odd tilt, the auroras seen by Hubble in 2011 are different than those seen by Voyager 2 in 1986, researchers said.

In 1986, Uranus was at the solstice point in its orbit, with its axis pointed at the sun. The auroras seen on the planet by Voyager 2 at the time lasted longer and occurred primarily on the planet's night side — which the Hubble Space Telescope cannot see from its vantage point in Earth orbit.

Hubble's 2011 view of Uranus's auroras, meanwhile, occurred during the planet's equinox, when the planet's rotational axis is perpendicular to the sun; an orientation that allows each of the planet's magnetic poles to face the sun once each day.

"This configuration is unique in the solar system," Lamy said.

The research will be detailed in a study appearing in the April 14 edition of the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.