How Music 'Awakens' Alzheimer's Patients

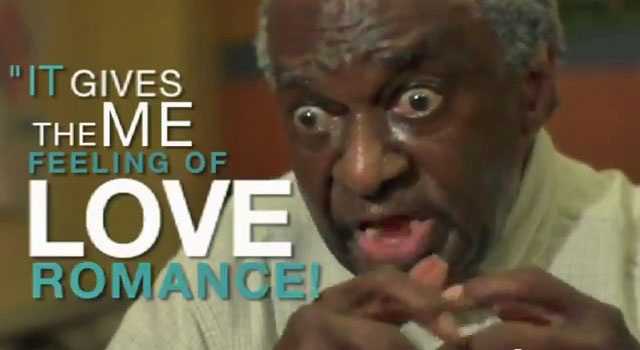

In a now-famous YouTube video, Henry, an elderly man with dementia, is transformed by the power of music. Initially slumped in a chair and unable to recognize his own daughter, Henry seems to be miraculously brought out of his stupor by a few minutes of music from his youth: He gushes about his favorite jazz singer, sings a few verses in a rich baritone and waxes poetic about how music makes him feel.

The poignant footage demonstrates a well-known but under-studied effect: Experts say music really can "awaken" Alzheimer's and dementia patients. Neurologists at the Boston University Alzheimer's Disease Center are leading the field in uncovering why music seems to affect memory and, more important, how music therapy can be used to improve the lives of those whose memories are fading.

Andrew Budson, associate director for research at the center, said there are currently two theories to explain the transformative effect of music on Henry and other dementia sufferers. First, music has emotional content, and so hearing it can trigger emotional memories — "some of the more powerful memories that we have," Budson told Life's Little Mysteries. These types of memories have the best chance of rising to the top in Alzheimer's patients.

Secondly, when people learn music, we store the knowledge as "procedural memory," the kind associated with routines and repetitive activities (also known as muscle memory). Dementia primarily destroys the parts of the brain responsible for episodic memory — the type that corresponds to specific events in our lives — but leaves those associated with procedural memory largely intact. Because we don't shed this memory as we grow old, we retain our appreciation for music.

Music's ability to tap into procedural memory and pull on our emotional heartstrings may mean it can do more than simply allow dementia sufferers to access pristine memories from the past. In 2010, the researchers discovered that Alzheimer's patients had a much easier time recalling song lyrics after the words had been sung to them than they could after the words had been spoken. "It suggested that music might enhance new memory formation in patients," said Nicholas Simmons-Stern, also at Boston University and lead author of the study.

Since then, the researchers have been investigating whether patients can learn vital information, such as when to take their medication, through song. According to Simmons-Stern, as-yet unpublished results lend hope to the idea, suggesting music will be a powerful tool for the treatment and care of dementia patients in the future. However, to have the intended effect, the music must ring true: "The lyrics need to fit the music in a way that's natural and enhancing, and the process of fitting is extremely important," he said. Repetition of the lyrics is also crucial.

Despite this progress, the scientists still aren't sure whether music aids in patients' ability to form new memories by harnessing procedural memory, strengthening new knowledge by tying it emotions, or doing some combination of the two. It may not be surprising that they are only now getting a handle on music's influence on the minds of elderly people; they have barely studied its effects on the rest of us. "I think that music as a scientific area of study has not been thought to be legitimate or mainstream until very recently," Budson said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Even in the firm hands of science, music is slippery: Like love, it is such a complex neural stimulus that scientists struggle to determine the interplay between lyrics and tune, sound and meaning. Simmons-Stern said what they know is this: "Every patient, and pretty much anyone, could benefit from having more music in their lives."

Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover. Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries and join us on Facebook.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.