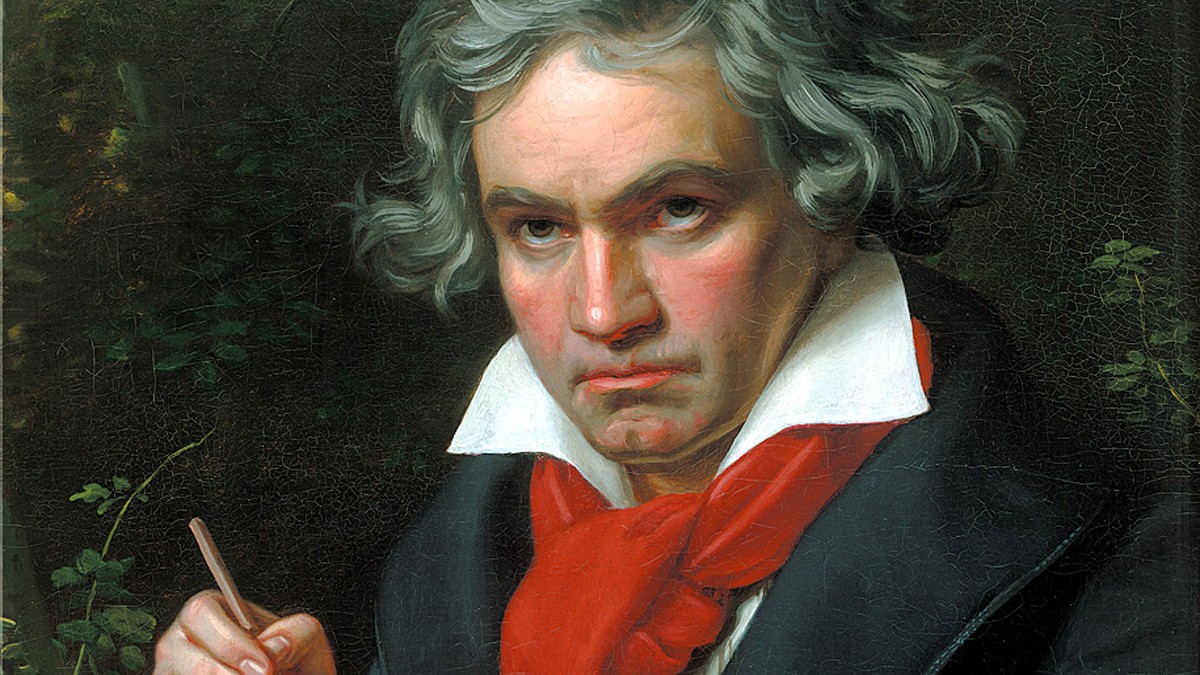

Beethoven's DNA sheds light on the mystery of his death

Five locks taken from Ludwig van Beethoven's head have revealed that he may likely have died from liver disease, not lead poisoning as was previously thought.

The world renowned composer Ludwig van Beethoven was infected with hepatitis B when he died, according to the first ever DNA analysis of the deaf musician's remains.

The genetic analysis, conducted on five locks of Beethoven's hair taken as mementos from his head during the last seven years of his life, also revealed that he had a high risk of liver disease. This genetic risk along with the hepatitis B infection, which likely also damaged his liver, may have played a role in his death. The discovery contradicts the widely-believed suggestion that the composer died from lead poisoning, but does not shed light on how he came to lose his hearing.

Born in 1770, Beethoven began to lose his ability to hear in his mid-to-late-20s, becoming completely deaf by his late-40s. He also suffered from increasingly severe gastrointestinal problems throughout his life, experiencing at least two attacks of jaundice, a symptom of liver disease.

Related: Scientists may have cracked the mystery of da Vinci's DNA

In 1802, as his ailments grew in severity, Beethoven asked his doctor friend Johann Adam Schmidt to uncover and publicize the strange disease he was suffering from, but Schmidt died 18 years before Beethoven. After Beethoven's death in 1827, a post-mortem revealed that he had severe liver scarring, also known as cirrhosis. Now, the new research, published Wednesday (March 22) in the journal Current Biology, has found the genetic and viral basis for his illness, fulfilling the composer's request at long last.

"We cannot say definitely what killed Beethoven, but we can now at least confirm the presence of significant heritable risk and an infection with hepatitis B virus," study co-author Johannes Krause, a professor of genetics at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology, said in a statement. "We can also eliminate several other less plausible genetic causes."

To crack the great composer's genetic code, the researchers first set about figuring out if the eight locks of his hair they had obtained from collections in the U.S. and Europe were authentic. After using DNA analysis to determine the age of the locks; comparing the DNA taken from each; and assessing the results alongside the paperwork for each one, the researchers concluded that five of the locks came from Beethoven. Among the three discounted locks was the hair previously studied to suggest that he died of lead poisoning; but the lock is now believed to have come from an Ashkenazi Jewish woman.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Further DNA analysis of the locks revealed the composer's high risk of liver disease, possibly caused by a genetic disorder called hereditary hemochromatosis. The risk factor did not exceed one that would go unnoticed by most people, but the researcher's believe Beethoven's well-documented love of alcohol, alongside his infection with hepatitis B — a virus which can damage the liver — could have caused him to develop liver disease.

"Taken in view of the known medical history, it is highly likely that it was some combination of these three factors, including his alcohol consumption, acting in concert, but future research will have to clarify the extent to which each factor was involved," study lead author Tristan Begg, a geneticist and doctoral candidate of Biological Anthropology at the University of Cambridge in the U.K., said in the statement.

The study also revealed a strange mystery in Beethoven's family history. Comparisons made with the composer's living relatives showed that, though some shared a paternal ancestor, their DNA did not match the Y-chromosome found in Beethoven's authenticated hair. The researchers say this is likely the result of an extramarital affair somewhere in Beethoven's ancestral line that begat offspring.

"We hope that by making Beethoven's genome publicly available for researchers, and perhaps adding further authenticated locks to the initial chronological series, remaining questions about his health and genealogy can someday be answered," Begg said.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based staff writer at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, among other topics like tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.