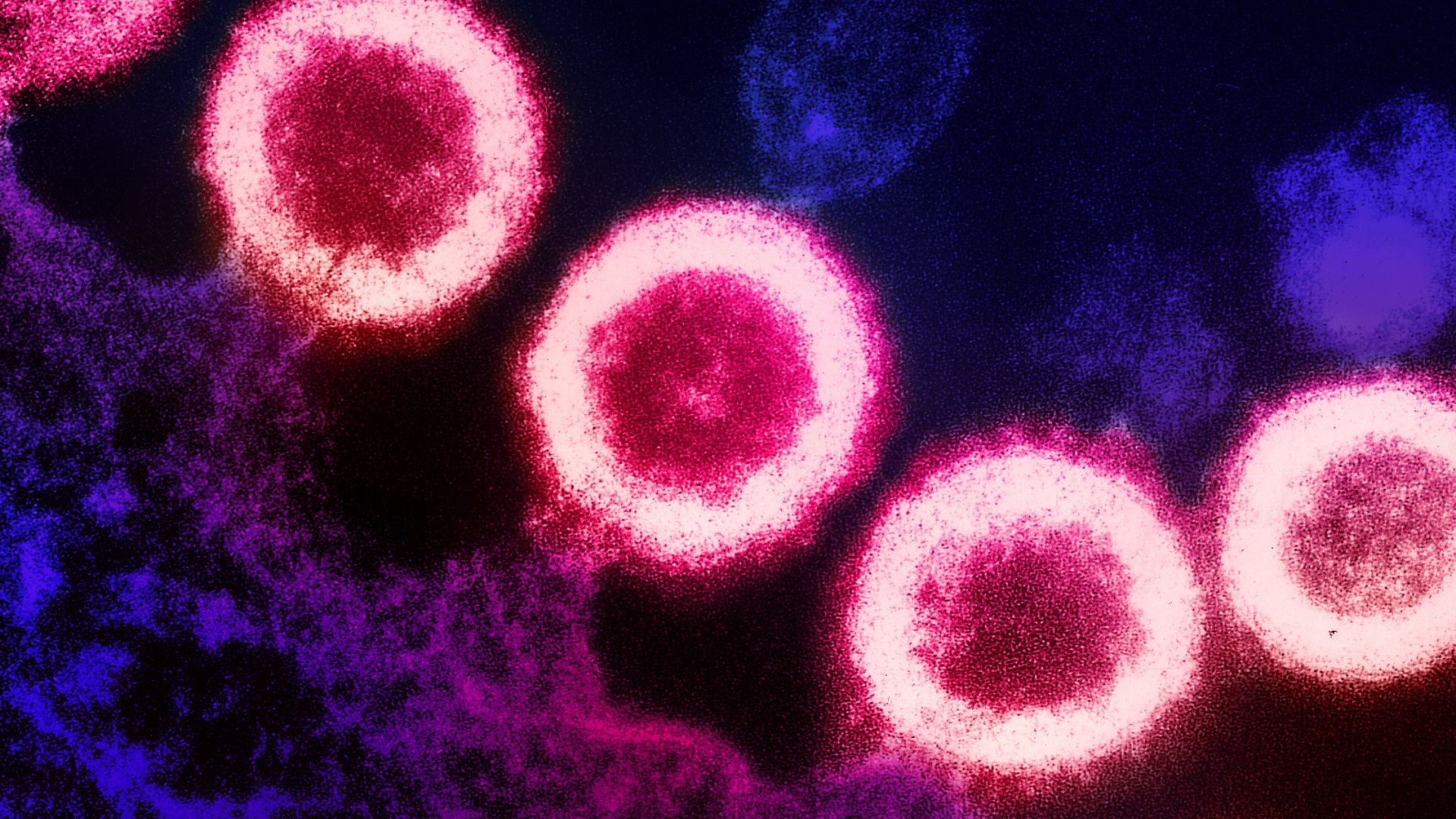

1st woman given stem cell transplant to cure HIV is still virus-free 5 years later

A woman who received a stem cell transplant to treat her HIV is still virus-free more than five years after the procedure and 30 months after she stopped taking HIV medication.

A woman known as the "New York patient" received a stem cell transplant to cure her HIV, and now, she's been virus-free and off her HIV medication for about 30 months, researchers report.

"We're calling this a possible cure rather than a definitive cure — basically waiting on a longer period of follow up," Dr. Yvonne Bryson, director of the Los Angeles-Brazil AIDS Consortium at the University of California, Los Angeles and one of the doctors who oversaw the case, said during a news conference held Wednesday (March 15).

Only a handful of people have been cured of HIV, so at this point, there's no official distinction between being cured and being in long-term remission, said Dr. Deborah Persaud, the interim director of pediatric infectious diseases at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, who also oversaw the case. Although the New York patient's prognosis is very good, "I think we're reluctant to say at this point whether she's cured," Persaud said at the news conference.

Bryson and her colleagues released early data on the New York patient in February 2022 and published more details of the case on Thursday (March 16) in the journal Cell. The new report covers the majority of the patient's case, up to the point when she had stopped taking antiretroviral therapy (ART) — the standard treatment for HIV — for about 18 months.

Related: UK man becomes second person cured of HIV after 30 months virus-free

The patient received a stem cell transplant in August 2017 and stopped taking ART a little over three years later. Now, she's been off the medication for roughly 2.5 years, and "right now, she's still doing very well, enjoying her life," Dr. Jingmei Hsu, director of the Cellular Therapy Laboratory at NYU Langone Health and one of the transplant team leaders, said at the news conference.

Earlier HIV cure cases — including definitive cures in men treated in London, Berlin and Düsseldorf, and one case of long-term remission in a man treated in Los Angeles — had received stem cell transplants taken from bone marrow as a dual treatment for both cancer and HIV. (The first patient cured of HIV, a man from Berlin, died in 2020 after a cancer relapse.)

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

All these transplants used bone marrow stem cells from adult donors who carried two copies of a rare genetic mutation: CCR5 delta 32. This mutation alters the doorway that HIV typically uses to enter white blood cells and thus blocks the virus from entering. After transplantation, the donor stem cells essentially take over the patient's immune system, replacing their old, HIV-vulnerable cells with new, HIV-resistant ones. To clear the way for the new immune cells, doctors wipe out the original immune cell population using chemotherapy or radiation therapy.

Like previous cases, the New York patient had both cancer and HIV and underwent chemotherapy prior to her transplant. However, she received stem cells taken from umbilical cord blood that contained the HIV-resistance genes. The umbilical cord blood was donated by an unrelated baby's parents at the time of delivery and later screened for the CCR5 delta 32 mutation.

To supplement those umbilical cord stem cells, as they were relatively few in number, the patient also received stem cells that had been donated by a relative, which helped bridge the gap as her HIV-resistant cells began to come in.

Because umbilical cord blood is easier to access than adult bone marrow, and more easily "matched" between donors and recipients, such procedures could become more common in the future. However, stem cell transplants wouldn't be appropriate for patients who are HIV-positive but don't have a second serious disease, like cancer, because it involves wiping out the immune system, Bryson said.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.