Wonder Woman: 10 Interesting Facts About the Female Body

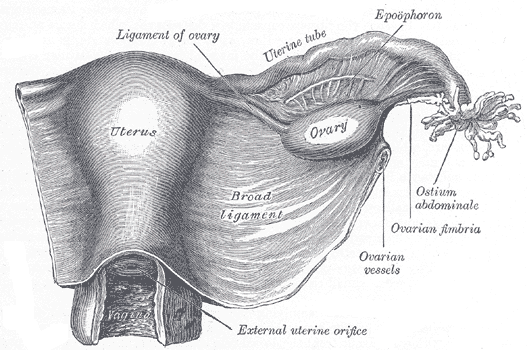

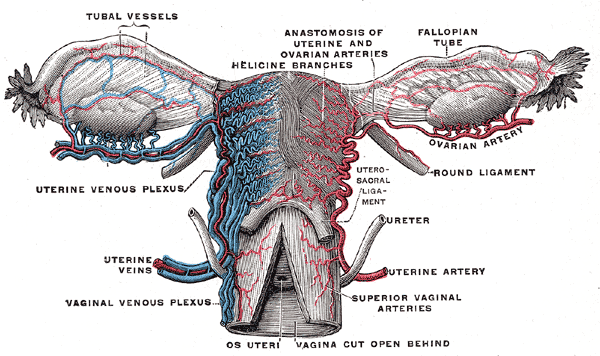

Mysteries of the female reproductive system

Scientists have made serious progress in understanding the female reproductive system since the days when ancient Greek physicians believed the womb could get antsy and wander around the body at will, causing all sorts of trouble. But women's reproductive tracts still hold an aura of mystery. Here are some wild facts about the uterus, vagina, G-spot and more — plus some mysteries that even scientists can't explain.

Da Vinci had it wrong

Leonardo da Vinci was a meticulous observer of human anatomy, illustrating images from dissected bodies that are still accurate today. But he fell short of perfection when sketching the female reproductive tract. According to Warwick University clinical anatomist Peter Abrahams, da Vinci's sketches of human uteruses look more like those of other animals. It may be that the difficulty of getting female corpses for study left da Vinci with no choice but to fill in the gaps in his knowledge with animal dissections, Abrahams told LiveScience.

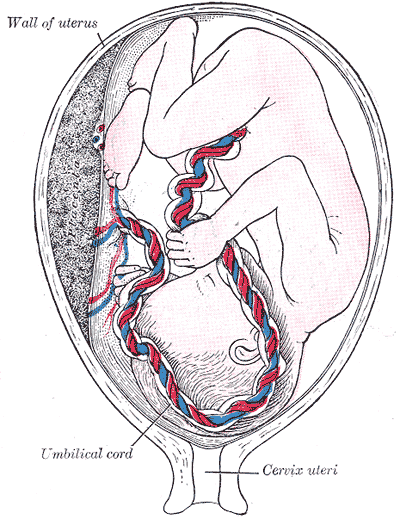

The uterus is ultra-elastic

When not in use, a healthy uterus is a small organ, measuring about 3 inches (7.5 centimeters) long and 2 inches (5 cm) wide. During pregnancy, that changes — fast. By about 20 weeks into pregnancy, the expanding uterus reaches all the way to the navel. The outer edge of the uterus reaches the lower edge of the rib cage by about 36 weeks.

It's acidic down there

The pH of the vagina is quite acidic, averaging around 4.5 on the pH scale (7 is neutral). That's about as acidic as beer or tomatoes. Busy microbe communities in the vagina maintain this acidity. For example, lactobacillus, a group of lactic acid-producing bacteria, dominates the ecosystem in many women's vaginas. These beneficial bacteria and their acidic output likely keep nasty bugs from moving in and colonizing the place.

The hymen: overhyped

Long heralded as an indicator of virginity, the hymen is really just a small piece of tissue ringing the vaginal opening. It can break or tear upon first sexual intercourse (or other penetration), or it can stretch; in other words, the presence or absence of a hymen says nothing about whether a woman has had sex.

In rare cases (about 1 in 2,000 births), a girl is born with an imperforate hymen, meaning there is no hole in the tissue to allow menses or discharge to pass through. This condition requires a minor incision to correct the problem.

The G-spot exists - or does it?

The G-spot, an area in the vagina said to be extra-sensitive to erotic stimulation, is a place of great contention. Many women certainly report "G-spot orgasms," studies have shown, but anatomical knowledge of the area remains thin. Most recently, a Florida surgeon named Adam Ostrzenski claimed to have found a rope of erectile tissue in the cadaver of an 83-year-old woman that could be anatomical proof of the G-spot. But other researchers say the structure could be anything, from an internal branch of the clitoris to a misidentified gland. And there's no history of whether the woman experienced vaginal orgasms, so claims about the structure's function are tough to make. For now, the question of whether the G-spot is a myth, an internal extension of the clitoris or its own unique bit of tissue remains a mystery.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Sometimes, things double

In a very rare condition called uterus didelphys, some women are born with not one, but two uteruses. This happens as the reproductive system is forming in the fetus; the uterus starts out as two tubes that join together to form one organ. When the tubes fail to fuse, each turns into its own uterus. Sometimes the vagina is duplicated, too, creating a forked path to each uterus. In many cases, the condition is symptom-free, though unusual menstrual bleeding or fertility troubles can be hints that something isn't right.

Pinpointing pregnancy isn't so simple

You can't be a little bit pregnant … but most women are considered pregnant before they've even conceived. Doctors typically measure pregnancy starting from the first day of the last menstrual period, because most of the time, women aren't sure exactly what day they conceived, but they can remember their last period. It's also not possible to detect the moment of fertilization, and pregnancy can't be confirmed until the developing embryo implants on the uterine wall (that's why at-home pregnancy tests aren't very accurate until at least a week after a missed period). [8 Odd Changes That Happen During Pregnancy]

Period protection has come a long way

Today, women can keep menstrual blood at bay with pads, tampons, menstrual cups or even hormones that shut down the period all together. Women of the past had to be more creative. Here, a short list of pre-pad methods to staunch menstrual blood, courtesy of the book "Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation" (St. Martin's Press 2009):

Softened papyrus (ancient Egypt)

Lint wrapped around wood (ancient Greece)

Paper (ancient Japan)

"bird's eye," absorbent cotton (1800s-1900s America)

Cellulose bandages (France, early 1900s)

Talking about your period could build bonds

Many cultures have menstruation rituals that declare a woman on her period as "unclean" or require her to avoid certain activities. Women in these cultures feel more shame about their periods, a March 2012 study found, but they also feel a greater sense of bonding with other women over this shared experience. Bringing periods "out of the closest" might help banish some of the mystery surrounding the female reproductive cycle, study researcher Tomi-Ann Roberts, a psychologist at Colorado College in Colorado Springs, told LiveScience.

Walt Disney Can Educate You

Which production company first used the word "vagina" on film? That would be Walt Disney Productions. In 1946, Disney produced an animated film called "The Story of Menstruation" for school health classes, sponsored by the company now known as Kimberly-Clark, makers of Kotex products. The film explains menstruation and gives helpful tips for happy periods, including how to "avoid constipation" and "stop feeling sorry for yourself."

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus