Dinosaur Fleas! Photos of Paleo Pests

Ouch! Flea Bites

Like today's mammals and birds, including our furry four-legged friends, dinosaurs may have been plagued by fleabites. Researchers have discovered the fossilized remains of what they are now calling two species, one of which lived 165 million years ago, and the other 125 million years ago. They were about 10 times the size of today's fleas and sported long, tough mouthparts that were likely able to penetrate the tough skin of a dinosaur. The finding adds to other "dinosaur flea" discoveries, suggesting perhaps a giant flea collar may have been in order.

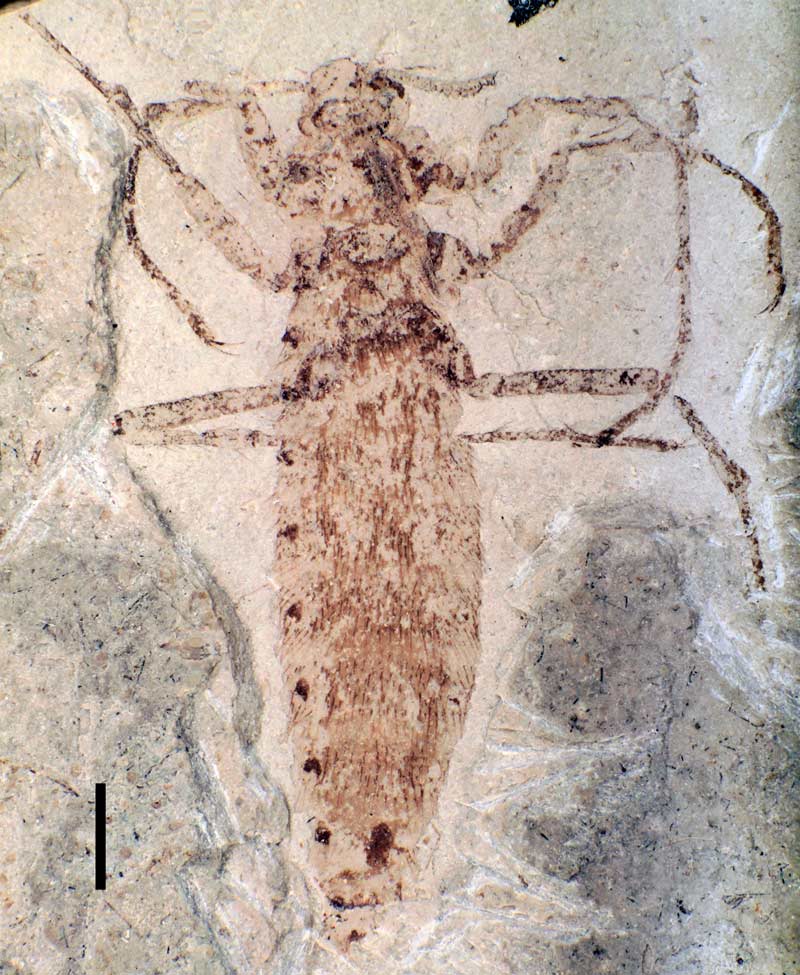

Insect Remains

Here, a compression fossil of the "dinosaur flea" called P. magnus, which rather than an impression fossil is actually the insect remains that have fossilized over time.

Serrated Stylets

The "dinosaur flea" called Pseudopulex jurassicus would have lived about 165 million years ago, using its lengthy and serrated mouthparts to suck the blood of hosts, including dinosaurs.

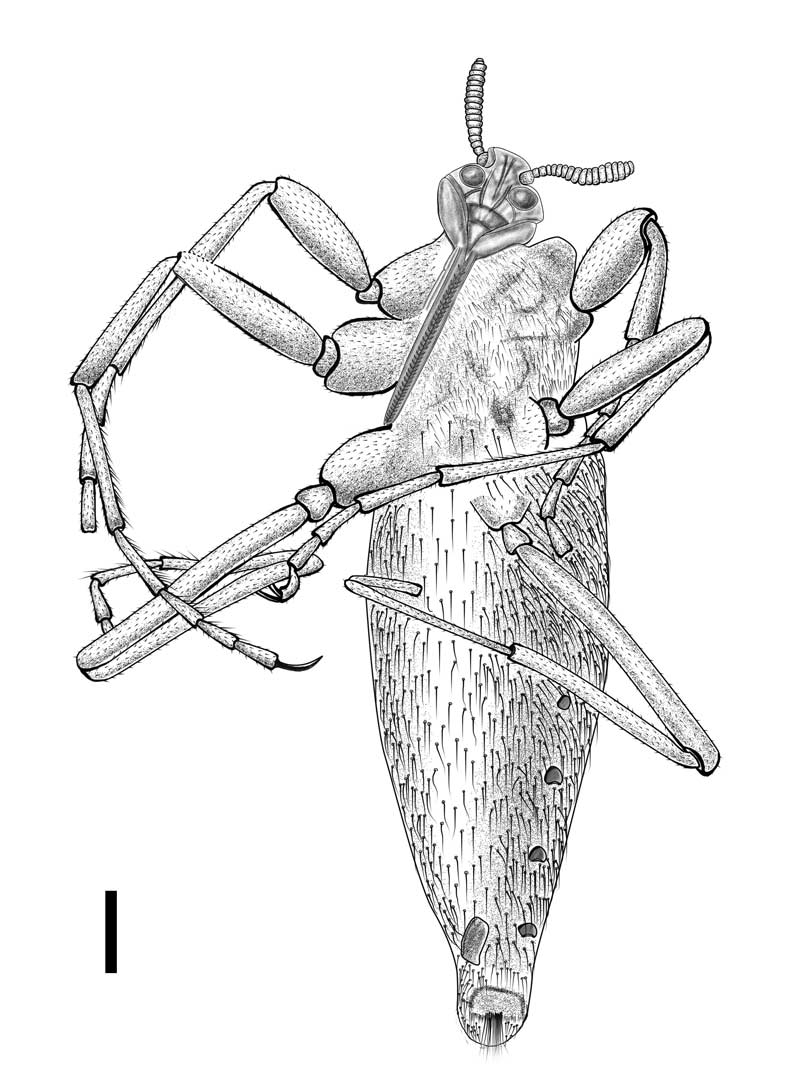

Don't Mess With Me!

The monster of the two newly identified "dinosaur fleas," called P. magnus, lived about 125 million years ago. Its body, shown here in a line drawing, extended 0.9 inches (22.8 mm), and it sported serrated mouthparts reaching nearly 0.20 inches (5.2 mm) in length.

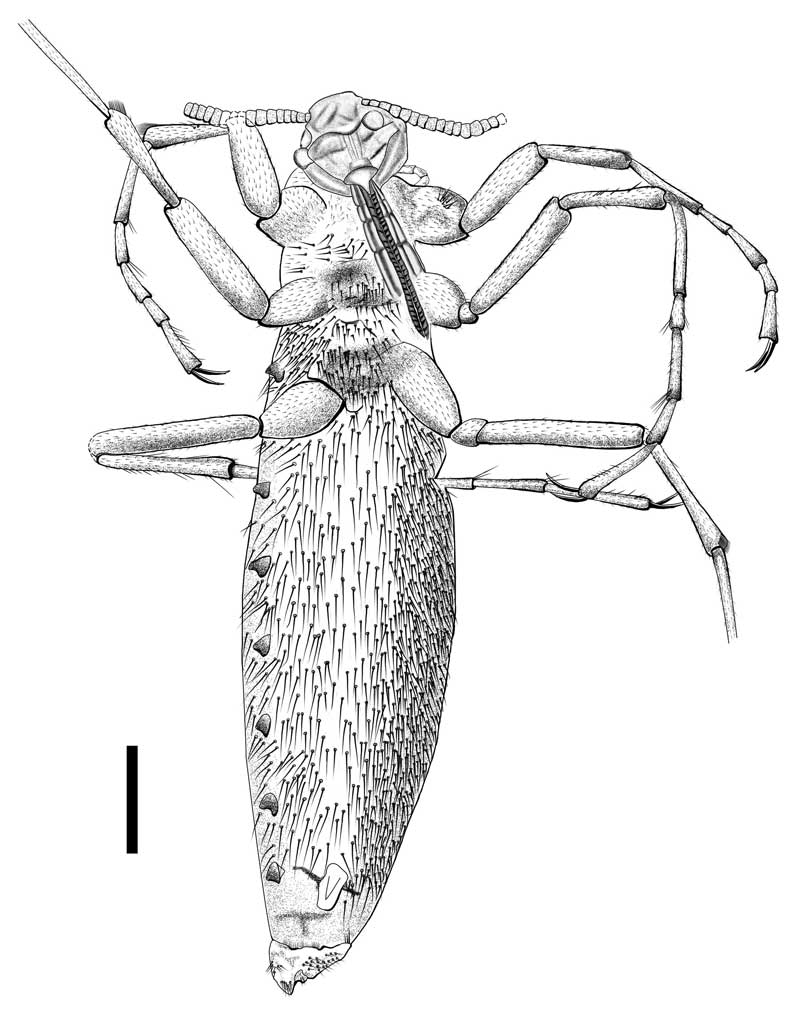

Dinosaur Blood

The flealike insect called P. jurassicus, shown here in this line drawing, may have fed on the blood of feathered dinosaurs such as Pedopenna daohugouensis and Epidexipteryx hui.

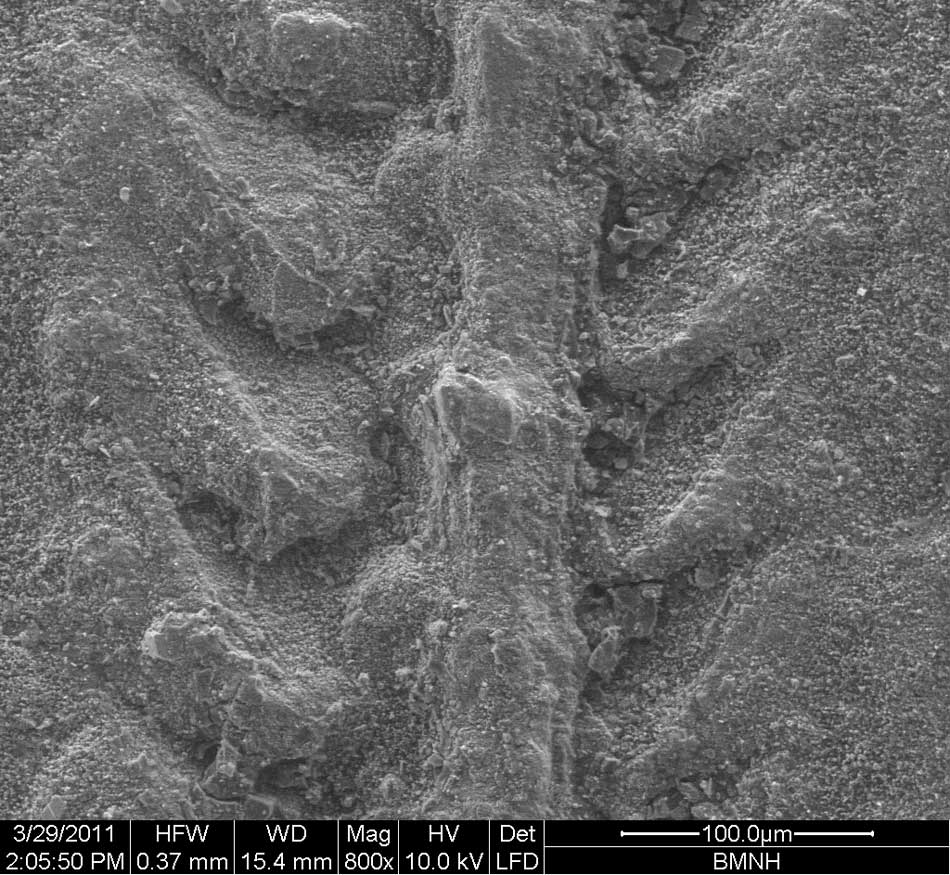

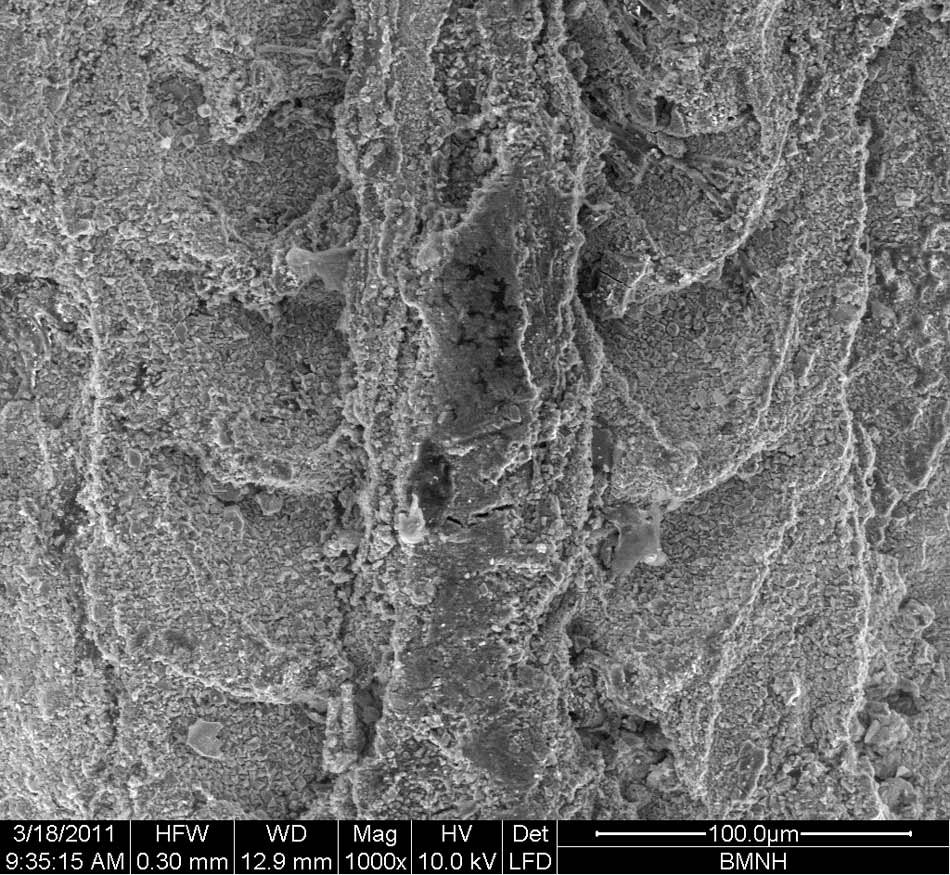

Menacing Mouthparts

The flealike insects sported saw-blade teeth along their lengthy mouthparts, part of which are shown here from one of the fossils P. magnus.

Mouthy Insect

Shown here, part of the mouthparts of the "dinosaur flea" called P. jurassicus.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

More Dino Fleas

The flealike insects, P. magnus and P. jurassicus, resemble the fossils of two other fleas reported in the journal Nature in 2012. Shown here, a male flea fossil from the early Cretaceous period.

Jurassic Fleas

A female (left) and male (right) flea from the middle Jurassic in China.

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.