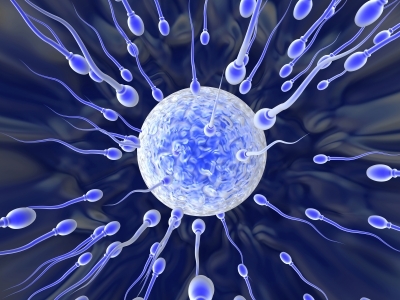

Sperm Act Like Bumbling Drunks on Way to Egg

Making a baby seems to rely on bumbling, crawling sperm, new research suggests, putting the kibosh on the popular notion that sperm are strong swimmers, whipping their tails back and forth to navigate though the uterus toward their ultimate goal of infiltrating the egg.

By studying sperm in tiny channels, researchers have discovered their travels can be arduous; instead of swimming merrily through the uterus, sperm cells tend to follow the walls of the reproductive tract, crawling along and inching around corners, frequently colliding with each other and with the walls.

"I couldn't resist a laugh the first time I saw sperm cells persistently swerving on tight turns and crashing head-on into the opposite wall of a micro-channel," study researcher Petr Denissenko, of the University of Warwick, in the United Kingdom, said in a statement. [5 Myths About the Male Body]

Hugging walls

As sperm navigate the female reproductive tract, they must negotiate complex, convoluted channels of tissue, which the researchers call "potentially tortuous geometry."

To see how they do this, the researchers put the sperm through an obstacle course in the lab, which involved sperm cells maneuvering micro-channels, 100 micrometers wide, or about the width of a human hair or the thickness of a coat of paint. The channels had either 90-degree corners, or wavy, circle-shaped corners. The sperm tend to have trouble dealing with these sharp turns, the researchers said.

"When the channel turns sharply, cells leave the corner, continuing ahead until hitting the opposite wall of the channel," the authors write in the paper, published today (May 7) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Where and when the sperm careen away from the corner depends on the viscosity of the liquid they are moving through.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

They also found that sperm from different donors reacted slightly differently to the tests done in viscous fluids, probably because their head shape and tail stroke patterns are different.

Best of the bunch

This research could eventually help treat infertility, the researchers said. "Through research like this we are learning how the good sperm navigate by sending them through mini-mazes," study researcher Jackson Kirkman-Brown, of the University of Birmingham in the United Kingdom, said in a statement.

Combining their findings with previous research suggesting the shape of the sperm head can impact swimming ability, Kirkman-Brown said, "we believe new methods of selecting sperm, perhaps for quality or even in certain non-human species for sex, may become possible."

They are working to figure out the characteristics that make sperm good navigators, what might separate those that succeed in fertilizing the egg from those that don't.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter, on Google+ or on Facebook. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.