Our Ancestors' Squishy Skulls Led to Bulging Brains

A new analysis of an old human ancestor fossil indicates that human brains started growing 2.5 million years ago, about the time humans started walking upright.

An unfused seam on the fossil's head indicates the skull was still pliable for several years after birth, giving the brain time to grow. An imprint of the brain on the inside of the skull also gave researchers a good view of the developing human brain.

"These findings are significant because they provide a highly plausible explanation as to why the hominin brain might grow larger and more complex," study researcher Dean Falk, of Florida State University, said in a statement. When humans started walking upright, it put pressure on infant skulls to stay flexible, allowing them to continue to grow for several years, the researchers suggest.

Small bones

Belonging to a 3- to 4-year-old Australopithecus africanus, nicknamed "Taung Child," the fossil skull was discovered in 1924 and dates back to about 2.5 million years ago. The specimen was initially discovered in a lime mine in South Africa, and was the first specimen of this species of hominin.

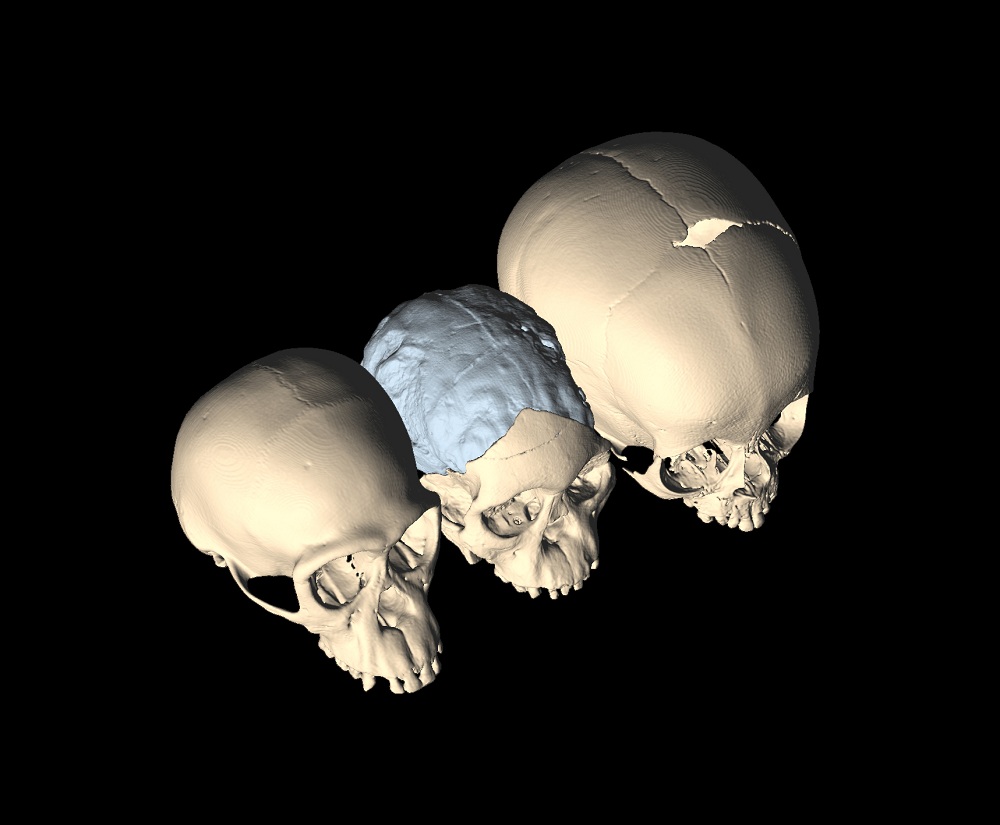

The researchers used three-dimensional scans to analyze the skull, which includes most of the face, jaw and teeth, as well as a natural internal cast of the braincase; they also compared their results with other hominid skulls, including those of chimpanzees and bonobos.

Such scans allowed the researchers to determine that the joints between the child's skull plates (called the metopic suture) hadn't fully fused, a uniquely human trait.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Walking upright

These brain joints close quickly after birth in monkeys and other apes, the researchers said, but in humans, this fusion happens much later. This flexibility in the skull may have existed to help with the birthing, since passing an infant with a large head though the birth canal can be tricky, especially after the hips were reconfigured for bipedalism.

The flexibility until later in life would have also let the prefrontal cortex, a brain area crucial for advanced cognitive capabilities, expand and grow over time. The researchers could see from the imprint of the brain on the inside of the skull that these brain areas had started expanding and changing.

This flexible feature "probably occurred in conjunction with refining the ability to walk on two legs," Falk said. "The ability to walk upright caused an obstetric dilemma. Childbirth became more difficult because the shape of the birth canal became constricted while the size of the brain increased. The persistent metopic suture contributes to an evolutionary solution to this dilemma."

The study was published today (May 7) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter, on Google+ or on Facebook. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.