Nobel Prize in Medicine goes to discoverers of hepatitis C

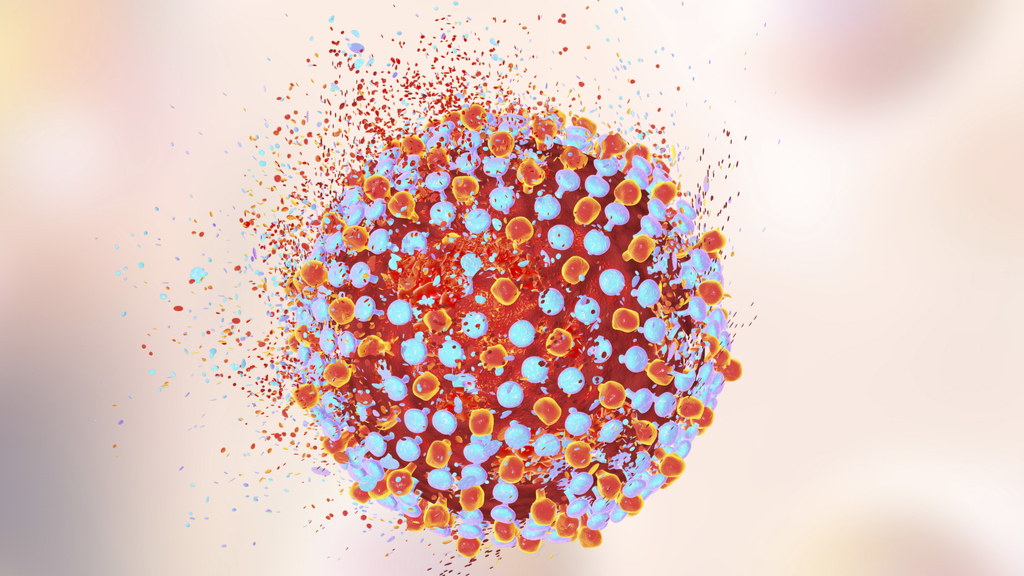

Three scientists won the 2020 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for their discovery of hepatitis C, a blood-borne virus that can cause chronic inflammation of the liver, leading to severe scarring and cancer.

The researchers Harvey Alter, Michael Houghton and Charles Rice "made seminal discoveries that led to the identification of a novel virus, hepatitis C virus," the Nobel Committee wrote in a statement. Two other forms of viral hepatitis — hepatitis A and B — had already been discovered at the time, but most cases of chronic hepatitis remained unexplained, they noted.

"The discovery of hepatitis C virus revealed the cause of the remaining cases of chronic hepatitis and made possible blood tests and new medicines that have saved millions of lives," the committee wrote. The scientists' award-winning work took place between the 1970s and 1990s, and enabled doctors to screen patients' blood for the virus and cure many of the disease, Science Magazine reported.

Related: 7 revolutionary Nobel Prizes in medicine

The word "hepatitis" derives from the Greek words for "liver" and "inflammation," and in addition to hepatitis viruses, the condition can arise from alcohol and drug use, bacterial infections, parasites and autoimmune disorders where the immune system attacks the liver, Live Science previously reported. Hepatitis A and E typically cause short-term illness and are transmitted through food or water contaminated with fecal matter. Hepatitis B and C, on the other hand, can lead to chronic infections and are transmitted through blood and other bodily fluids.

Physician and geneticist Baruch Blumberg won the 1976 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine for first identifying hepatitis B, a discovery that led to both diagnostic tests for the virus and a successful vaccine, the committee wrote. However, even after this discovery, many cases of chronic hepatitis continued to crop up in patients who received blood transfusions, hinting that a second blood-borne virus might also cause the disease.

Alter found that the illness, which he called "non-A, non-B" hepatitis, could be transmitted from humans to chimpanzees through blood and had the characteristics of a virus. Houghton later led work to clone the virus and named it hepatitis C. Rice examined the virus's genetic material, known as RNA, and performed genetic engineering experiments to learn how the pathogen causes hepatitis in chimps and humans. These experiments revealed that some forms of the virus do not cause disease, but an "active" form with specific genetic characteristics does.

Collectively, the three scientists' discoveries led to the development of highly sensitive blood tests and antiviral drugs for hepatitis C; the new treatments can cure about 95% of hepatitis C patients, Science Magazine reported. "For the first time in history, the disease can now be cured, raising hopes of eradicating hepatitis C virus from the world population," the Nobel Committee wrote.

That said, about 71 million people still live with chronic hepatitis C infections, worldwide, and the World Health Organization estimates that 400,000 people died of the disease in 2016, according to Science Magazine.

A big problem is "getting drugs to people and places where they desperately need them," John McLauchlan, a professor of viral hepatitis at the University of Glasgow, told The Associated Press, noting that the disease primarily affects poor populations and people who use drugs.

Originally published on Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and was previously a news editor and staff writer at the site. She holds a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other outlets. Based in NYC, she also remains heavily involved in dance and performs in local choreographers' work.