Hidden Alien Planet Revealed by Its Own Gravity

Detective astronomers have discovered at least one unseen alien planet, and possibly another, around a distant star by observing the odd behavior of a planet already known to orbit the same star.

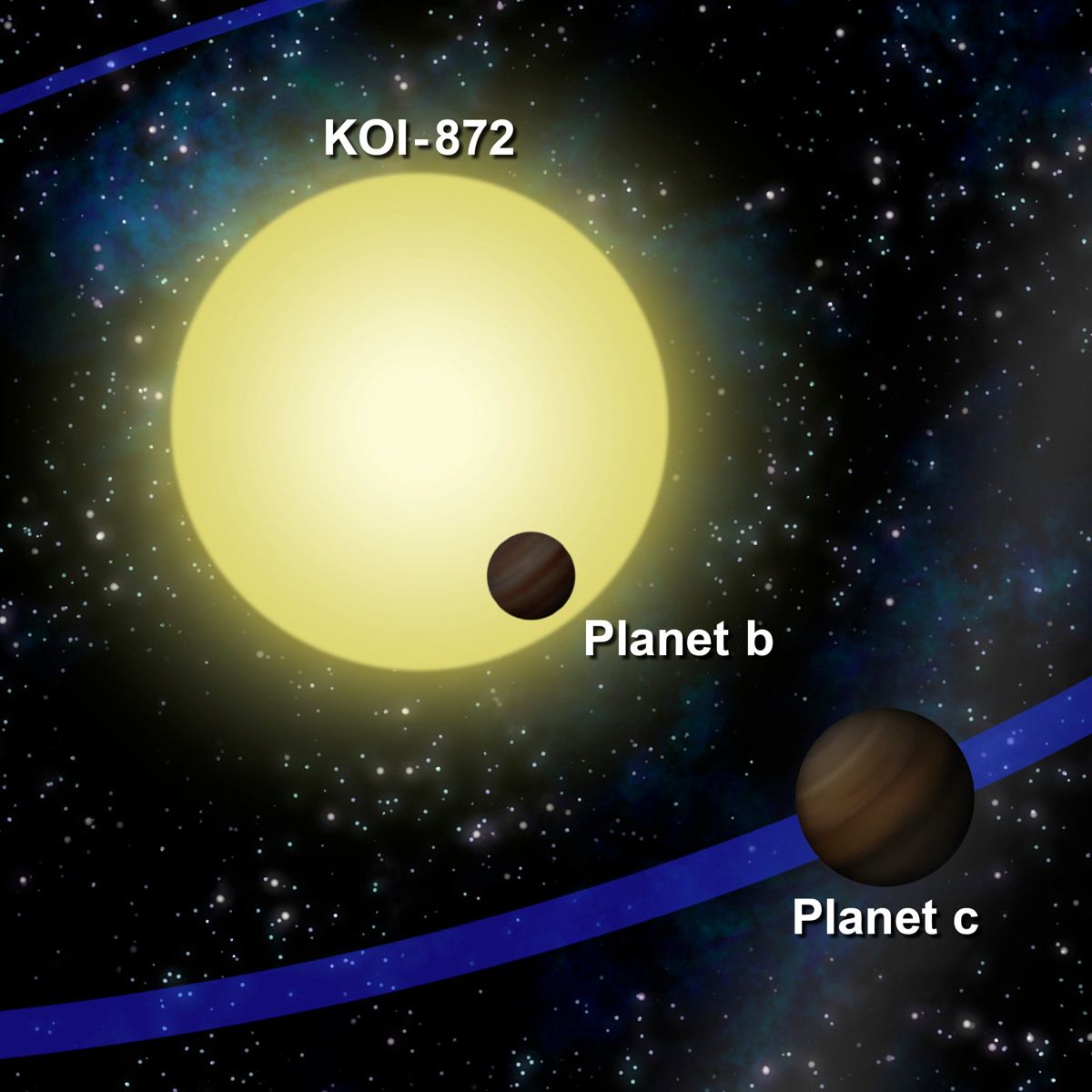

The newfound planet has about the mass of Saturn and orbits its host star once every 57 days. It was revealed by its gravitational effects on the previously known planet around the parent star KOI-872. The find is an apparent validation of what scientists call the transit timing variation method of finding extrasolar planets.

The idea of looking for oddities in a main planet's transit of its star to search for other planets was suggested in 2005, but "this is the first occasion where there is great confidence that the method works," said astronomer David Nesvorný of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo., who led the new study.

In fact, when the researchers looked in more detail at the system, they found signs of yet another planet, one only a bit larger than our own world. This "super-Earth" is likely circling very close to the star with an orbital period of 6.8 days.

Here's how the alien planet detective story played out:

The first look at data from NASA's planet-hunting telescope Kepler had identified only one planet around the star KOI-872. But a closer inspection by scientists outside the Kepler team revealed telltale signs of an extra planet.

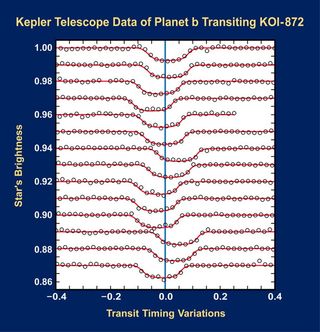

As part of its systematic search for alien planets, Kepler looks for stars whose brightness dims periodically — a signal that something, presumably a planet, is passing in front of it and blocking its light. The Kepler team identified a light dip in KOI-872 (KOI stands for "Kepler Object of Interest") and attributed it to a planet that orbited the star every 34 days. However, that timing appeared to vary by a few hours.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The planet should show transits equally spaced, which is not the case," Nesvorný said. "Sometimes the transit is two hours late, sometimes two hours early."

Using a computer model, Nesvorný and his colleagues concluded that the most likely explanation for the timing variations was the presence of another planet in the system, the Saturn-mass world. Their calculations suggested a likelihood greater than 99 percent that this mystery planet exists. [Gallery: A World of Kepler Planets]

Nesvorný and his team are now combing through the wealth of Kepler data for signs of exomoons — moons orbiting alien planets. So far none has been found.

"It mainly depends on if you can have really large moons, because if the moon is small, it wouldn't change transits too much," Nesvorný said. "At some point the first exomoon will be discovered. My guess is it will happen within a few years from now."

After the Kepler team runs its main analysis of data, it releases the data publicly to any scientists who want to study it.

"This is an enormous amount of data, so there's no way the Kepler team would have time to look at everything," Nesvorný said. "I think there are many more additional gems waiting to be discovered in the data set, either by the Kepler team or by scientists not related to Kepler."

The new discovery is detailed in a paper published in the May 11 issue of the journal Science.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com assistant managing editor Clara Moskowitz on Twitter @ClaraMoskowitz. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.