Ancient 'Loch Ness Monster' Suffered Arthritis

Ancient creatures resembling stout-necked Loch Ness Monsters apparently developed arthritis in their monster jaws, revealing that even such lethal killers could suffer from and eventually succumb to diseases of old age, researchers find.

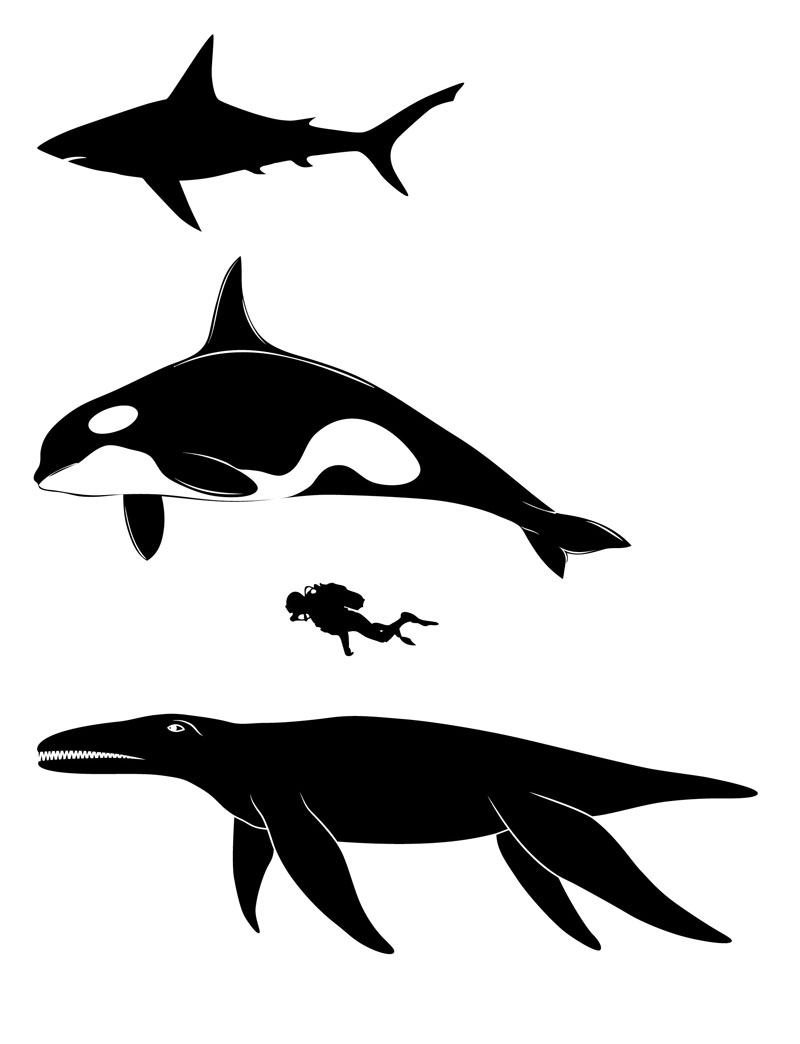

Scientists reached that conclusion while investigating the fossil of an extinct marine reptile known as a pliosaur. The carnivore was apparently an old female extending some 26 feet (8 meters). It had a 10-foot-long (3 meters), crocodilelike head, short neck, whalelike body and four powerful flippers to propel it through water to hunt down prey.

"This pliosaur, like many of its relatives, was truly huge," researcher Michael Benton, a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Bristol in England, told LiveScience. "To stand beside its skull and realize that it is 3 meters long, and massive and heavy as it is, that it once functioned with muscles and blood vessels and nerves, is amazing. You can lie down inside its mouth."

Normally, with huge jaws and teeth about 8 inches (20 centimeters) long, this pliosaur could have ripped most other animals apart. However, paleontologists found this specimen was apparently afflicted with an arthritis-like disease.

Old lady pliosaur

Benton and his colleagues analyzed an approximately 150-million-year-old specimen of Pliosaurus that had been unearthed in 1994 by fossil collector Simon Carpenter and held since then in the Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery in England.

The beast would have lived in what is now southern England, back when the area was covered in warm, shallow seas. "Imagine the Mediterranean or Florida," Benton said. Other fossils from the site include smaller marine reptiles such as marine crocodiles, turtles and plesiosaurs, other Loch Ness Monster-like creatures upon which the pliosaur likely fed, as well as fish and shellfish. [Loch Ness Madness: Our 10 Favorite Monsters]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The skeleton had a low ridge of bone running from front to back on top of its skull. Investigators regarded it as female because males were thought to have taller ridges. Its large size and fused skull bones suggested maturity. The investigators noticed the reptile had signs of a degenerative condition similar to human arthritis.

"The most exciting aspect of this research for me is the arthritic condition, which has never been seen before in these or similar Mesozoic reptiles," researcher Judyth Sassoon at the University of Bristol told LiveScience.

Crooked jaws

The degenerative condition had eroded the pliosaur's left jaw joint. This would have knocked its lower jaw askew.

"In the same way that aging humans develop arthritic hips, this old lady developed an arthritic jaw and survived with her disability for some time," Sassoon said. "But an unhealed fracture on the jaw indicates that at some time the jaw weakened and eventually broke.

"With a broken jaw, the pliosaur would not have been able to feed, and that final accident probably led to her demise."

Marks on the lower jawbone from the pliosaur's upper teeth suggest the predator lived with a crooked jaw for many years, long enough to damage its own bones.

"You can see these kinds of deformities in living animals, such as crocodiles or sperm whales, and these animals can survive for years as long as they are still able to feed. But it must be painful," Benton said. "Remember that the fictional whale Moby-Dick, from Herman Melville's novel, was supposed to have had a crooked jaw." [Album: World's Biggest Beasts]

Despite its condition, the animal was evidently still able to hunt and avoid being eaten by other pliosaurs, which were the top predators in their environment, the researchers noted.

"To see the jaws distorted out of place substantially enough that the front tips of the jaws overlapped, and the lower teeth made definite holes in the upper jaw, 5 centimeters (2 inches) off to the side, and that it lived with this agonizing pain for so long, evidently still managing to feed, is quite impressive," Benton wrote in an email. "This was an old, weather-beaten animal when it died."

Sassoon, Benton and Leslie Noè detailed their findings online May 15 in the journal Palaeontology.

Sassoon is currently investigating another pliosaur and hopes to better understand the creatures' diversity and habits and how they mechanically adapted to their huge size.

"I plan to carry on poking around in museum collections, looking for interesting specimens, until I am too old to lift a paintbrush and wipe the dust off a fossil," Sassoon said.