Elephant Seals Seen Traveling Oceans for Food

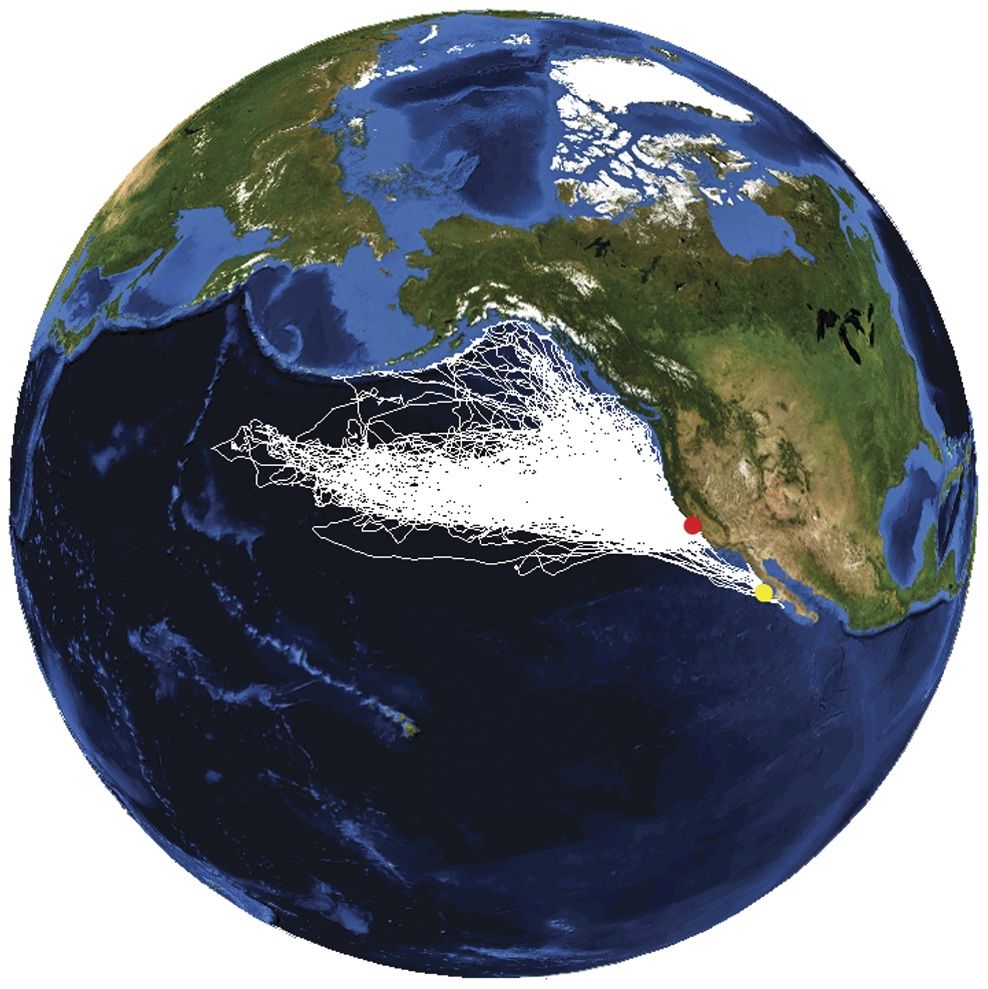

Elephant seals travel through the entire northeast Pacific Ocean on foraging trips in search of prey, newly released tracking data shows.

These findings highlight the adaptability of elephant seals, suggesting that they may be able to withstand environmental perturbations such as climate change because the population is not dependent on a single foraging strategy.

The study, published yesterday, May 15, in the journal PLoS ONE, is one of the largest datasets on the species, including nearly 300 animals, revealing their migrations and diving behavior in unprecedented detail.

The researchers found that individual seals pursue a variety of different foraging strategies, but most of them target one oceanographic feature in particular — a boundary zone between two large rotating ocean currents, or gyres.

Along this boundary, the cold nutrient-rich waters of the sub-polar gyre in the north mix with the warmer waters of the subtropical gyre, driving the growth of phytoplankton and supporting a robust food web. Presumably, this leads to a concentration of prey along the boundary.

"The highest density of seals is right over that area, so something interesting is definitely going on there," study researcher Patrick Robinson, of the University of California at Santa Cruz, said in a statement.

Smaller numbers of female elephant seals feed in coastal regions, pursuing bottom-dwelling prey along the continental shelf, or in other areas outside of the boundary zone such as around seamounts.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Among these is a large female that feeds near Vancouver Island and holds the record for deepest recorded dive by an elephant seal. Her dives recorded in the data in the paper include one dive to 5,765 feet (1,747 meters), well over a mile deep, and another reaching 5,788 feet (1,754 meters) into the depths of the ocean, Robinson said.

Foraging is especially important for female elephant seals, because the amount of food a female is able to find on foraging trips directly affects her breeding success and, if she gives birth, her pup's growth rate and chances of survival. "If foraging is not good, the pups are smaller at weaning because the females produce less milk," Robinson said.

The researchers also monitored the health of the seals and track birth rates over time. Before and after each migration, the researchers get weights and blood samples from the tagged seals, which always return to the same rookery.

Most of the animals in this study were tagged at the rookery on Año Nuevo Island in Northern California, where researchers have been studying elephant seals for decades. But some were tagged at Islas San Benito, 690 miles (1,150 kilometers) southeast.

"A lot of those animals travel much further to get to foraging areas in the north, so they might spend an extra week traveling, and we wanted to see how that affects them," Robinson said. "The animals from San Benito that do go up to feed at the boundary zone do fine, but we also found that many of them stayed closer to home, feeding along the continental shelf, and they were successful too."