Jellyfish Hunt Hurts Pacific Leatherback Turtles

When it comes to leatherback turtles, the world's largest species of sea turtle, there's a conundrum: The species itself is critically endangered, but at least one leatherback population is stable — on the rise, even — while others plummet.

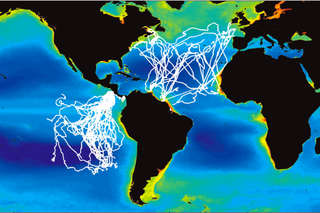

Now, researchers may have discovered why some of these turtles are doing better than others. Studying two leatherback turtle populations, one that is declining and one that seems to be increasing, the researchers say the answer might be simple: food.

"We saw very big differences in their traveling speeds from their nesting beaches to their foraging grounds," said Helen Bailey, an ecologist at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science who led the study. "We take that to mean one population is stopping to forage on a nice dense patch of prey, while the other group keeps moving because it's constantly in search of food."

These differences in swimming and eating habits may hold important clues for helping leatherback turtles around the world recover and thrive, Bailey told OurAmazingPlanet.

Dine in or drive-through?

Atlantic leatherback turtles seem to be doing OK, but the Pacific population could be extinct in the near future, Bailey said.

Leatherback turtles everywhere are often victims of bycatch, the unintentional netting and killing of turtles while fishing for other animals, but leatherbacks in the Pacific Ocean face another problem. Climate patterns like the El Niño-Southern Oscillation cause huge variations in temperature and productivity in the Pacific Ocean, making it hard for some animals to find reliable food supplies. These challenges, combined with leatherbacks' advanced breeding age (around 15 years for females), mean that the Pacific leatherback turtle population has taken a serious hit over the last two decades.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To figure out the difference between these two groups, Bailey looked at how the turtles swim. Using data from leatherbacks that had been tagged and tracked by satellite, she found that Atlantic leatherbacks have two modes of travel: fast (12-28 miles per day, or 20-45 kilometers per day) and slow (less than 9 miles per day, or 15 km per day). Pacific leatherbacks, on the other hand, have only one: a cruising speed of about 13 miles per day (21 km per day). [In Images: Tagging & Tracking Sea Turtles]

Atlantic leatherbacks seem to run from one smorgasbord to another, stopping at a dense patch of jellyfish (their main food source) to eat until it's gone. Pacific leatherbacks never find dense patches of jellyfish, so they swim at the same rather fast speed the whole time, Bailey said.

"They're constantly searching for food," Bailey said. "If you have to keep moving, you're not gaining quite as much energy because even if you manage to eat along the way, you're still expending some energy by traveling."

In other words, the main difference between the two populations is that Atlantic turtles can dine in and chow down, while Pacific leatherbacks have to settle for the drive-through window and eating on the run.

Adults are important

Bailey's findings, detailed in the May issue of the journal PLoS ONE, point to new leatherback turtle conservation strategies.

"It's really highlighted very strongly the importance of protecting adult leatherbacks," Bailey said in an interview.

Because leatherback turtles have long life spans (about 30 years), they've adapted to survive jellyfish shortages by waiting to build nests and lay eggs after they've found a stable food supply. So far, most efforts have focused on protecting leatherbacks' nesting beaches. That's still important, Bailey said, but it may be even more important to protect adult turtles that are old enough to reproduce.

"They really have not adapted in any way to being harvested," Bailey said. "So when adults are killed by, for example, getting caught in fishing nets, then that does have a huge impact on the population and its ability to increase."

This story was provided by OurAmazingPlanet, a sister site to LiveScience.