HPV Vaccine for Teens: Doctors Voice Their Concerns

The vaccine to prevent cervical cancer, the fourth most deadly cancer for women worldwide, has faced difficulty in gaining acceptance in the United States, and a new survey may indicate why.

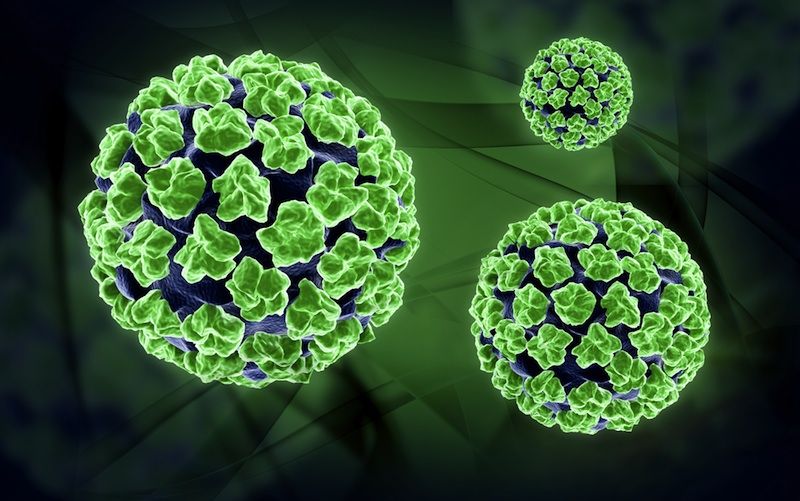

The vaccine in question, marketed as Gardasil and Cervarix, prevents infection of HPV, the human papillomavirus, a sexually transmitted virus that is the primary cause of cervical cancer and a major cause of anal, vaginal and penile cancers. The HPV vaccine, approved by the FDA in 2006, is recommended for girls ages 9 and older, before they become sexually active.

In a survey of more than 1,000 U.S. physicians, some doctors reported they are opposed to the vaccine on moral grounds or have concerns about its cost, safety or efficacy. Although those in opposition represent a minority, many provided insightful written explanations as to why they are reluctant to recommend the vaccine to patients. [5 Dangerous Vaccination Myths]

A survey analysis, conducted by the Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, Fla., is detailed online in the Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. The researchers, led by Susan Vadaparampil, say that because a doctor's recommendation is a driving force behind a parent allowing a child to receive this largely non-mandatory vaccine, understanding doctors' concerns is crucial to improving vaccination rates.

A common virus

Most sexually active men and women will acquire at least one strain of HPV in their lives, and half of sexually active young adults under age 25 are infected, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Only certain strains of HPV cause cancer, however, and most cervical infections can be detected by a pap smear and treated before becoming cancerous. Nevertheless, each year more than 12,000 women develop cervical cancer. Worldwide there are about a half million cases annually and 250,000 related deaths, according to the World Health Organization.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The HPV vaccine isn't the first vaccine associated with a sexually transmitted disease. The hepatitis B virus is spread primarily through unprotected sex. The "HepB" vaccine is given to infants and lasts upwards of 25 years. HepB lacks controversy, though, because children can acquire the liver-damaging hepatitis B non-sexually through infected members in their household. [Quiz: Test Your STD Smarts]

The HPV vaccine, on the other hand, is chiefly about sex and has all the buzzwords to make it controversial: teenage girls, cervix, vagina and penis.

Moral objections

The doctors' survey indicated that some physicians — particularly family physicians, as opposed to gynecologists and pediatricians — echoed complaints voiced by some parents: that the vaccine given to preteens or young teenagers promotes promiscuity, lulls girls into a false sense of security, and discourages them from seeking regular gynecological screening.

There is no evidence to support these concerns, the researchers said. In fact, general vaccine usage dictates otherwise: No one knowingly steps on dirty nails, emboldened by the power of a tetanus shot. Also, studies reveal that teenagers are more aware of other common and immediate hazards of unprotected sex: HIV, gonorrhea and teen pregnancy. Thus teenagers would not have unprotected sex based solely on protection offered against something that prevents cancer decades down the line.

However, Vadaparampil said the concept that girls would neglect future screening deserves further investigation, because this would have serious consequences.

Most doctors concerned about the vaccine cost — more than $100 for each of the three required shots, although usually free for the uninsured — were not against the HPV vaccine, but rather wanted to reduce the financial burden imposed on parents. As for safety and efficacy, many doctors said that these concerns would likely diminish over time.

Clock ticking

Fewer than 45 percent of girls in the target group between ages 13 and 18 have received one or more of the three shots, according to the CDC. That's less than half of the vaccination rates for most childhood vaccines. The average age of sexual debut for U.S. girls is 17.4.

The percentage of girls who complete the HPV vaccine series is dropping, according to a paper published last month in the journal Cancer. This surprised the researchers, from the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston, who thought they'd uncovered a rise in vaccine rates.

In essence, the older the girl, the less likely she will seek her follow-up shots. Girls most likely to get three complete shots, spaced out over the course of a year, were ages 9 to 12. But even for this group, the rate is falling: In 2006, 57 percent of preteens who got the first shot got the next two; in 2009, only 21 percent did the same, the study showed.

The two studies combined suggest the need to have girls vaccinated as early as possible — young enough to maintain a three-shot schedule, and young enough to view the vaccine with innocence for what it is, a cancer preventative, not a magical condom.

Christopher Wanjek is the author of the books "Bad Medicine" and "Food At Work." His column, Bad Medicine, appears regularly on LiveScience.

Christopher Wanjek is a Live Science contributor and a health and science writer. He is the author of three science books: Spacefarers (2020), Food at Work (2005) and Bad Medicine (2003). His "Food at Work" book and project, concerning workers' health, safety and productivity, was commissioned by the U.N.'s International Labor Organization. For Live Science, Christopher covers public health, nutrition and biology, and he has written extensively for The Washington Post and Sky & Telescope among others, as well as for the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, where he was a senior writer. Christopher holds a Master of Health degree from Harvard School of Public Health and a degree in journalism from Temple University.