Giant Dinosaur Skeleton Found in Museum Drawers

A curator has rediscovered a nearly complete giant Barosaurus skeleton hidden for years in museum drawers.

The skeleton was pieced together from an array of giant bones now known to belong to an 80-foot-long (24 meters) dinosaur whose footsteps shook the Earth some 150 million years ago.

The Barosaurus skeleton discovery was made this year, not during a field dig but in the halls of the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada as Associate Curator of vertebrate paleontology David Evans dug through collections of isolated bones once assumed to belong to as many different dinosaurs.

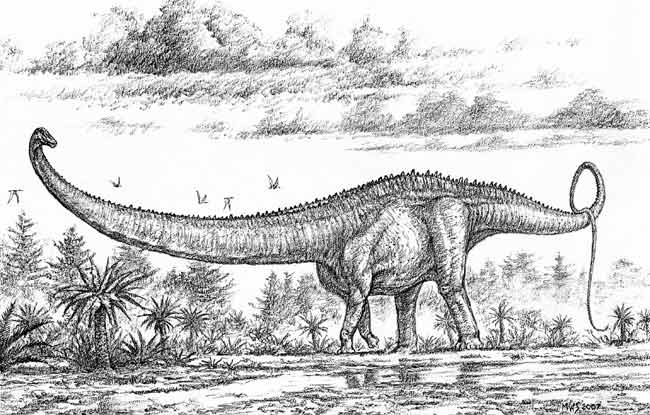

The Jurassic Period dinosaur weighed about 33,000 pounds (15,000 kilograms) and belongs to the four-legged, plant-eating group of dinosaurs known as sauropods, some of which sport long necks and tails, like this new specimen. The largest sauropods reached nearly 100 feet (30 meters) in length and tipped the scales at more than 50 tons (50,000 kilograms).

Evans was tasked with finding a sauropod dinosaur to display in a forthcoming exhibition at the museum. After months of researching dead ends, Evans hit the treasure-hunt jackpot. He spotted a reference in an article by famed sauropod expert Jack McIntosh suggesting that a Barosaurus skeleton was stored at the ROM.

The ROM’s databases turned up squat. Evans finally connected disparate dinosaur dots, realizing that what were thought to be isolated bones scattered throughout the collections room actually belonged to a single dinosaur—a Barosaurus.

"We were searching for an iconic sauropod skeleton, and we had one under our noses the whole time," said Evans, who is also an assistant professor in the Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology at the University of Toronto in Canada. "When all the parts were pulled together, we realized just how much of the animal the ROM actually had—the better part of a skeleton of a rare, giant dinosaur."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Barosaurus skeleton includes four massive neck vertebrae, a complete set of back vertebrae, the pelvis, 14 tail vertebrae, both upper arm bones, both thigh bones (each more than 55 inches (140 centimeters) in length), a lower leg and various other fragments.

The skeleton is currently being mounted. When complete, the 3-D resurrection will form the centerpiece of the ROM’s new James and Louise Temerty Galleries of the Age of Dinosaurs, opening the weekend of Dec. 15 and 16.

The skeleton will be the only "real" Barosaurus mounted in a life pose in the world, Evans said. The American Museum of Natural History in New York displays a mounted skeleton made of casts of real bones, because the real fossil bones are too heavy to display in this way, it says.

The newly discovered skeleton is from the Morrison Formation in the western United States and was collected in the early part of the 20th century from what is now Dinosaur National Monument, Utah. The ROM acquired the skeleton in 1962 through a trade organized by former ROM Curator Gordon Edmund with the intention of installing it in a 1970 dinosaur gallery renovation.

The Museum traded, among other things, two duck-billed dinosaur skeletons for what was then thought to be a Diplodocus, an identification that was later corrected by McIntosh. Due to a lack of space the Barosaurus did not make it into the 1970 gallery. After Edmund retired in 1990, the specimen's story was forgotten, and all its pieces were separated on different shelves and in different drawers in the ROM’s collection rooms through various moves as a result of construction done in the early 1980s.

The Museum now has nicknamed the specimen "Gordo" in honor of Edmund.

- A Brief History of Dinosaurs

- Image Gallery: Dinosaur Fossils

- Vote: Dinosaurs that Learned to Fly

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.