Whale's Big Gulp Aided by Newfound Organ

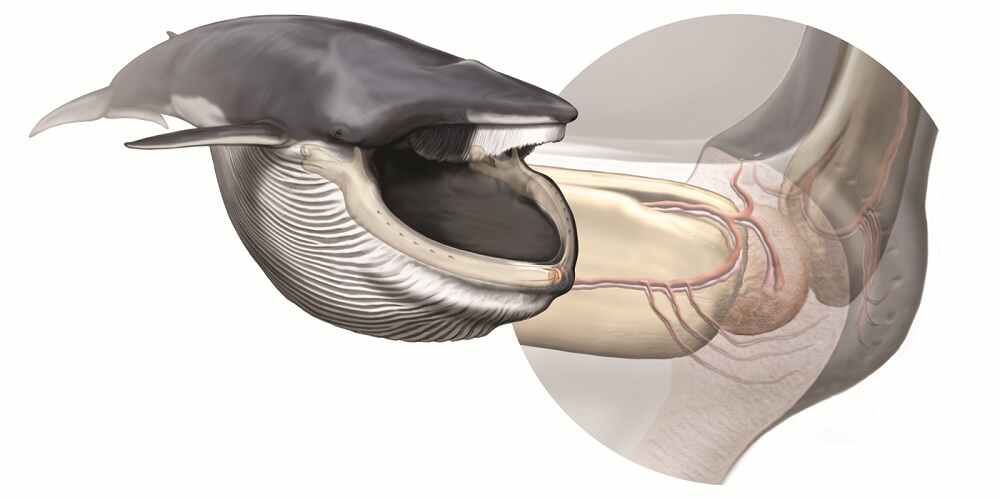

Whales that feed by taking big gulps of the ocean have a special sensory organ in the middle of their jaws that helps them regulate their unique feeding methods, researchers find. The once-hidden organ prevents injury as the whales gulp whale-size mouthfuls of water.

"We think this sensory organ sends information to the brain in order to coordinate the complex mechanism of lunge-feeding, which involves rotating the jaws, inverting the tongue and expanding the throat pleats and blubber layer," study researcher Nick Pyenson, of the Smithsonian Institution, said in a statement.

The researchers studied rorqual whales, the largest group of baleen whales. They include nine species like the blue whale, which can weigh up to 165 tons (150 metric tonnes). The smallest rorqual whale is the northern minke whale, which weighs in at nearly 10 tons (9 metric tonnes).

The results are detailed in tomorrow's (May 24) issue of the journal Nature.

Big bites

To feed, a rorqual whale will lunge at a spot in the water, open its mouth hugely wide, stretching a large patch of soft tissue between its jaws, and engulfing a school of fish or tiny shrimp-like krill and water about the size of the whale itself in one bite. The process takes about six seconds.

The water then gets filtered back into the ocean through baleen at the front of the whale's mouth, which slowly returns to normal size while retaining the food caught.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To facilitate this type of feeding the whales have two large connected jawbones very loosely attached to the rest of their skull. The researchers studied the connection between these two bones in fin and minke whales, both young and old specimens, which were caught commercially in Iceland.

Special sensor

The researchers discovered a special new organ in the cartilage joint between these two elastic jawbones. The organ is about the size of a grapefruit, and is full of nerves and blood vessels, which seem to feed into structures in the mouth that detect changes in pressure, called mechanoreceptors.

These mechanoreceptors seem to respond to the rotation of the whale's jaws while the mouth is opening, something that puts pressure on the joint between the jawbones; the receptors also sense the expansion of the soft tissue inside the mouth.

The changes the organ senses are sent back to the brain, to help coordinate feeding, the researchers suspect. The information could be used to regulate how fast the mouth opens and how much the throat pouch expands to maximize the volume of water captured, all without overdoing the amount of stress put on the jaw and mouth.

"In terms of evolution, the innovation of this sensory organ has a fundamental role in one of the most extreme feeding methods of aquatic creatures," study researcher Bob Shadwick, of the University of British Columbia, said in a statement.

Shadwick added that lunge-feeding adaptations appear to have evolved before today's whales ballooned in size. As such, he said, "it's likely that this sensory organ — and its role in coordinating successful lunging — is responsible for rorquals claiming the largest-animals-on-Earth status."

You can follow LiveScience staff writer Jennifer Welsh on Twitter, on Google+ or on Facebook. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter and on Facebook.

Jennifer Welsh is a Connecticut-based science writer and editor and a regular contributor to Live Science. She also has several years of bench work in cancer research and anti-viral drug discovery under her belt. She has previously written for Science News, VerywellHealth, The Scientist, Discover Magazine, WIRED Science, and Business Insider.