Possible Newfound Alien Planet is Falling to Pieces

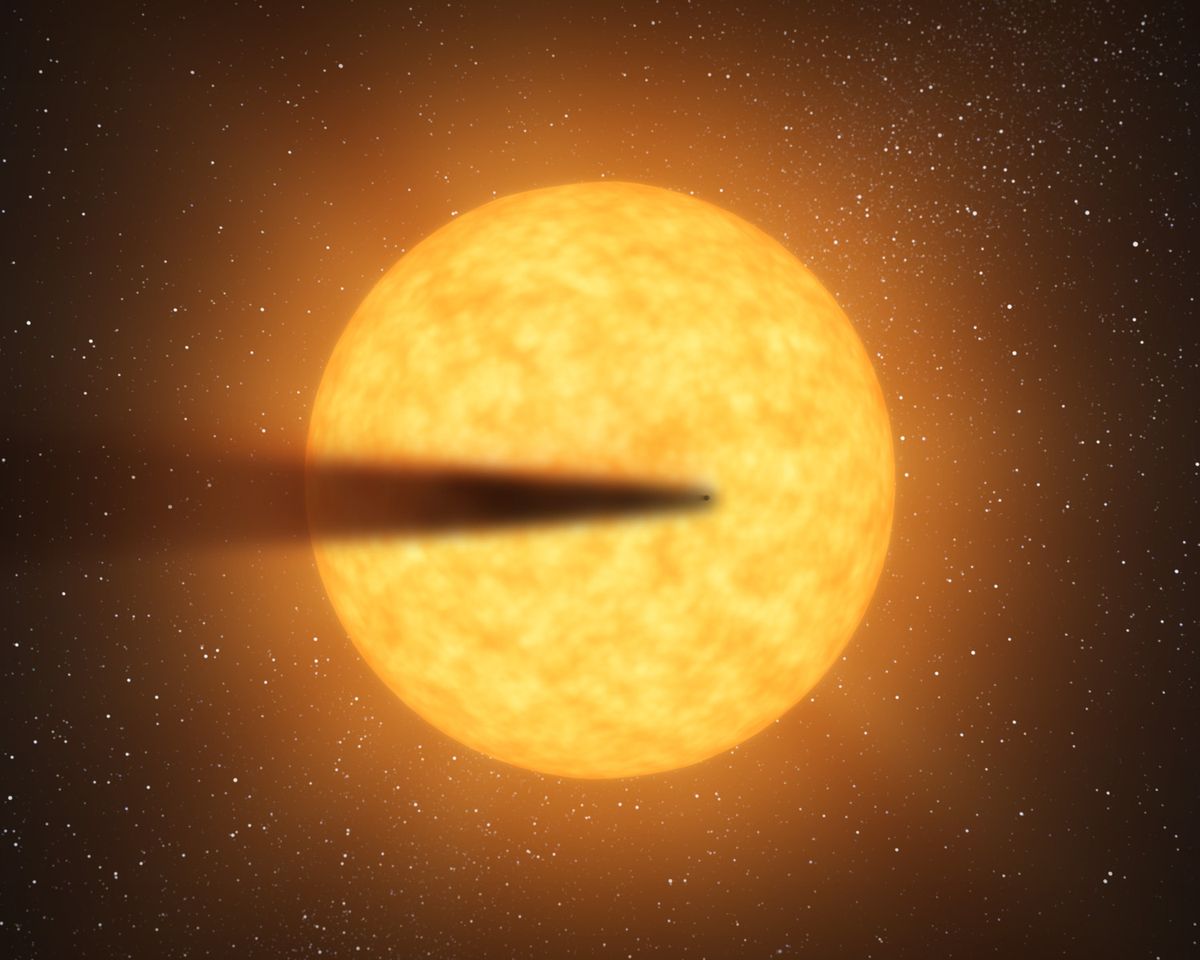

A potential alien planet that is so close to its parent star that it appears to be disintegrating from the scorching heat was recently found by a team of astronomers. The planetary candidate is only slightly larger than the planet Mercury, and researchers estimate that it is shedding so much material that it could completely disintegrate within 100 million years.

Astronomers at NASA and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) detected the tiny planet, which is located roughly 1,500 light-years away, using data from the planet-hunting Kepler mission. As the possible planet evaporates, researchers theorize that it is followed by a trail of dust and debris, similar to the tail of a comet.

The dusty planet circles its host star once every 15 hours, which indicates that the star, named KIC 12557548, likely heats the planet to blistering temperatures of about 3,600 degrees Fahrenheit (1,982 degrees Celsius). The researchers hypothesize that under these conditions, the planet's rocky material melts and evaporates, creating a trailing wind of gas and dust in space.

"We think this dust is made up of submicron-sized particles," study leader Saul Rappaport, a professor emeritus of physics at MIT, said in a statement. "It would be like looking through a Los Angeles smog."

Using data from NASA's Kepler mission, the researchers found the planet candidate after identifying an unusual light pattern coming from the KIC 12557548 star.

The space-based Kepler telescope stares at more than 150,000 stars in our Milky Way galaxy. The planet-hunting observatory records the brightness of each star at regular intervals. To find planets and planetary candidates, Kepler looks for dips in the stars' brightness, which could signal a planet crossing in front, or transiting. [Gallery: A World of Kepler Planets]

Rappaport and his colleagues noticed that light from KIC 12557548 dropped by different intensities every 15 hours. This suggested that something was blocking the star at regular intervals, but by varying degrees.The $600 million Kepler telescope launched in March 2009 and has discovered more than 2,300 potential alien planets to date. NASA recently announced that the mission will be extended through at least fiscal year 2016.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The bizarre nature of the light output from this star with its precisely periodic transitlike features and highly variable depths exemplifies how Kepler is expanding the frontiers of science in unprecedented ways," Jon Jenkins, Kepler co-investigator at the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence (SETI) Institute in Mountain View, Calif. "This discovery pulls back the curtain of how science works in the face of surprising data."

After mulling several possibilities, the researchers hypothesized that the dips in the star's light could be caused by an amorphous, shape-shifting body.

"I'm not sure how we came to this epiphany," Rappaport said. "But it had to be something that was fundamentally changing. It was not a solid body, but rather, dust coming off the planet." The parent star is smaller and cooler than the sun, but the potential has one of the shortest orbits ever detected, taking roughly 15 hours to make one circle around the star. At an orbital distance of only twice the width of the star, the surface temperature is estimated to be smoldering hot, exceeding 3,000 degrees Fahrenheit (1,648 degrees Celsius).

Ultimately, more observations will be needed to confirm that it is a bona fide planet, and to determine what processes are at work. But, the research also introduces new explanations for how planets can disappear.

"This might be another way in which planets are eventually doomed," said Dan Fabrycky, a member of the Kepler Observatory science team who was not involved in the research. "A lot of research has come to the conclusion that planets are not eternal objects, they can die extraordinary deaths, and this might be a case where the planet might evaporate entirely in the future."

The detailed findings of the study are published in the Astrophysical Journal.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.