5 Alien Parasites and Their Real-World Counterparts

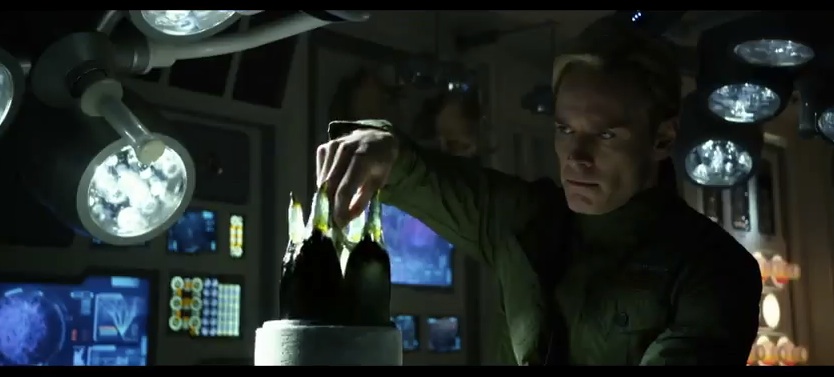

Paranoid about parasites? Best avoid the upcoming film "Prometheus," a quasi-prequel to the 1979 horror film "Alien" that hits American theaters June 8.

The "Alien" franchise is responsible for giving the world one of the ugliest alien parasites ever, the bloody "chestburster" that soon grows into a deadly hunter. But director Ridley Scott isn't the only moviemaker to look to parasites for inspiration when creating terrifying space monsters. Here's a look at the parallels between real-world parasites and Hollywood aliens.

1. Mind Control to Major Tom

Film directors love their mind-controlling parasites. Stargate SG-1 provides a particularly icky example: the Goa'uld Symbiote, a snake-like creature that penetrates its host's neck and wraps itself around the spine, taking over control.

Goa'uld are evil, arrogant creatures with a plan for galactic domination. Real-life parasites don't share those goals (as far as we know…) but many are capable of mind control. One creepy example, Ophiocordyceps unilateralis, is a fungus that attacks ants. Once it invades an ant, the fungus compels the poor insect to scramble down to low leaves, finally biting a vein on the underside of a perfectly placed leaf. Having done its job, the "zombie" ant then dies. To make matters worse, its body becomes a greenhouse for the fungus, forming a protective shell where the organism can grow until it bursts a spore-bearing stalk through the unfortunate insect's head. [Gallery: Zombie Ants]

2. Suggestive Symbiosis

Ants aren't the only ones susceptible to mind-control invasions — though for mammals, the mind control is slightly more subtle. Take Toxoplasma gondii, a parasitic protozoa that wants nothing more than to complete the sexual phase of its life cycle inside of a cat. T. gondii can conduct the asexual phase of its life cycle in other mammals (humans included), but it's a genius at getting back into a cat if need be. For example, a T. gondii-infected mouse loses its fear of cats, greatly increasing the likelihood that it will be eaten by a hungry feline and that the parasite can continue its life cycle unabated.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Humans can fall victim to T. gondii, too, and some researchers suspect that the parasite might have links to human mental health, including schizophrenia and brain cancer. According to some scientists, a high enough level of parasite infection in a society could change the culture as a whole.

Back in the realm of fiction, "Star Trek" writers invented a parasite with some striking T. gondii parallels. The burrowing Ceti eel slithers into its human host's ear and lodges in the cerebral cortex, rendering its host susceptible to suggestion. In the long run, infection by a Ceti eel can lead to madness — or death. [Invasion of the Alien Space Parasites (Infographic)]

3. Alien Inspiration

The chest-bursting alien in Ridley Scott's "Alien" was inspired by a real-life monster: parasitoid wasps. This group of wasps, which encompasses multiple species, lay their eggs in caterpillars, beetles, insects and other bugs. When the eggs hatch, they crunch their way out of their living incubator just like Scott's alien. One wasp species, Dinocampus coccinellae, targets ladybugs, which then sit on the wasp larvae like zombie nannies. The partially paralyzed, but still living, ladybug hosts usually die during this process. But about 25 percent survive, a 2011 study found. That's a better rate than the cast of "Alien."

4. Sexual Infection

The 1975 movie "They Came from Within" (originally titled "Shivers") features a parasite created by a mad scientist that turns human hosts into violent, sex-crazed fiends. Appropriately enough, the parasite can be transmitted via sexual activity.

Though it won't turn anyone into a sex zombie, a parasite called Trichnomonas vaginalis can be transmitted via intercourse. In fact, it's the cause of a very common sexually transmitted disease called trichomoniasis. Only 30 percent of the estimated 3.7 million Americans infected by this protozoa ever develop symptoms, which include itching, burning and genital inflammation. Luckily, a simple dose of oral antibiotics provides a cure.

5. Willing Infection

Star Trek's Trill Symbionts were worm-like creatures that lived in humanoid hosts from the planet Trill. These humanoid hosts willingly took on their parasitic pals. In fact, joining with a parasite was a competitive venture, with potential hosts having to pass certain tests and be approved by a special commission.

Believe it or not, some real-life people intentionally infect themselves with parasites, too. According to the still-controversial hygiene hypothesis, an increasingly sterile environment has led to a rise in autoimmune disorders and allergies, including debilitating disorders like celiac disease. Some brave pioneers have turned to helminthic therapy, swallowing parasitic worms in an attempt to get the immune system back on track.

The treatment is not yet approved in the United States, but researchers are working to understand whether it really works — and how. One case study of a man with ulcerative colitis, a type of inflammatory bowel disease, suggested that the worms stimulate gut mucus production, easing symptoms. If helminthic therapy proves helpful, perhaps the next generation of science fiction films will cast parasites as not villains, but sidekicks.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.