Artificial Platelets Mimic Nature to Stop Bleeding

Wounded soldiers or surgery patients could soon get new help to stop the bleeding. A lab has successfully created tiny, disk-shaped cells that mimic the human body's natural platelets, which allow blood to clot.

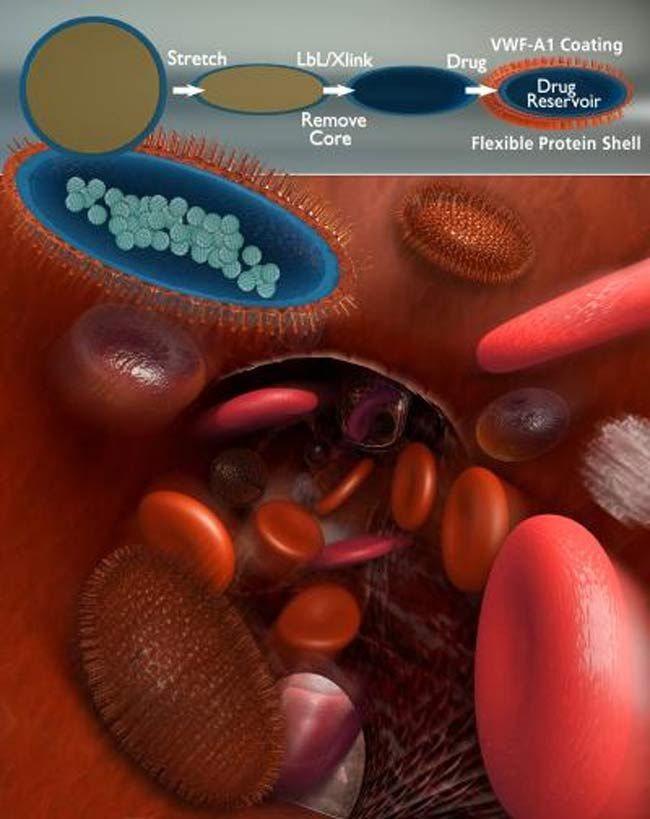

Such lab-made platelets could do much more than just form blood clots on wounds. They could act as messengers to deliver imaging markers for examining damaged blood vessels, or possibly carry clot-dissolving drugs to their targets in a person's bloodstream.

"The synthetic platelets can have profound implications in wound-healing problems for trauma and wounds arising in both battlefield situations and during surgery," said Frank Doyle, director of the Institute of Collaborative Biotechnologies at the University of California at Santa Barbara.

Platelets have an average size of just 2 to 4 micrometers, about 50 times smaller than the width of a human hair strand. (A micrometer is one millionth of a meter.) Over the past 100 years many labs have tried mimicking the form and function of platelets, but no method copied the actual physical features of natural platelets until now.

"In order to mimic the size, shape, and surface functionality of natural platelets synthetically, polymeric particles are particularly attractive," said Nishit Doshi, a chemical engineer at UC Santa Barbara. "However, polymeric particles are orders of magnitude more rigid than platelets."

The inflexibility problem required a clever solution. Researchers first used a polymeric core as the foundation for layers of proteins and other components making up the synthetic platelet. Then, once the platelet-shaped particle formed, researchers dissolved the rigid core to give the platelet flexibility.

Synthetic platelets may prove especially useful on battlefields because the supply of natural platelets has a short shelf life. They also could help patients who suffer from higher risks of bleeding because of low platelet counts. But the lab-made platelets first must undergo more testing and eventually reach clinical trials in human patients.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The findings from the study appeared May 29 in the online edition of the journal Advanced Materials.

This story was provided by InnovationNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.