Why Some People Blame Themselves for Everything

People prone to depression may struggle to organize information about guilt and blame in the brain, new neuroimaging research suggests.

Crushing guilt is a common symptom of depression, an observation that dates back to Sigmund Freud. Now, a new study finds a communication breakdown between two guilt-associated brain regions in people who have had depression. This so-called "decoupling" of the regions may be why depressed people take small faux pas as evidence that they are complete failures.

"If brain areas don't communicate well, that would explain why you have the tendency to blame yourself for everything and not be able to tie that into specifics," study researcher Roland Zahn, a neruoscientist at the University of Manchester in the United Kingdom, told LiveScience.

The seat of guilt

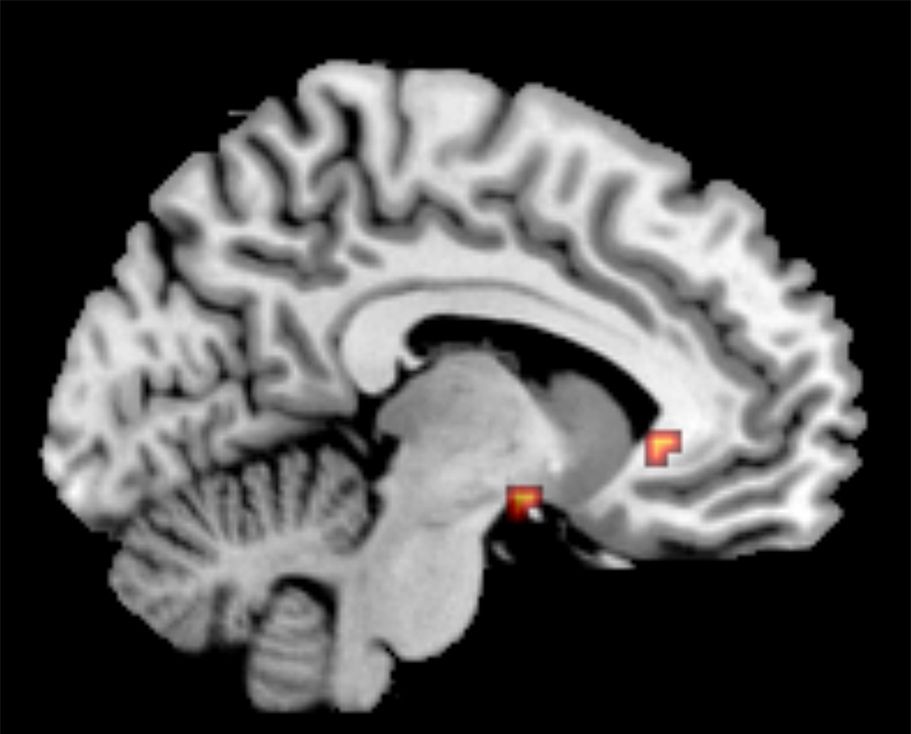

Zahn and his colleagues focused their research on the subgenual cingulated cortex and its adjacent septal region, a region deep in the brain that has been linked to feelings of guilt. Previous studies have found abnormalities in this region, dubbed the SCSR, in people with depression.

The SCSR is known to communicate with another brain region, the anterior temporal lobe, which is situated under the side of the skull. The anterior temporal lobe is active during thoughts about morals, including guilt and indignation.

The researchers suspected that perhaps the communication channels between the SCSR and the anterior temporal lobe help people feel guilt adaptively rather than maladaptively: "I messed up and shouldn't do that again," versus "I fail at everything, why do I even try?" [5 Ways to Foster Self-Compassion in Your Child]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers recruit 25 participants who had a history of major depression but who had been symptom-free for at least a year. The participants underwent functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), a type of brain scan that reveals blood flow to active areas of the brain. As their brains were scanned, the participants read sentences designed to illicit guilt or indignation. Each sentence featured the participant's name as well as the name of their best friend. For example, "Tom" might read a sentence like, "Tom acts greedily toward Fred," to elicit guilt. The sentence "Fred acts greedily toward Tom" would trigger indignation.

The researchers compared the brains of these once-depressed volunteers with the brains of 22 healthy, never-depressed controls, matched to the depressed volunteers on age, education and gender.

Guilt versus indignation

The resulting scans showed that while the SCSR and the anterior temporal lobe activate together in both guilt and indignation in healthy brains, the brains of the once-depressed individuals functioned quite differently. During feelings of indignation, the SCSR-anterior temporal lobe linkage worked fine. But during feelings of guilt, the regions failed to sync up so neatly.

Participants who were most prone to blame themselves for everything showed the greatest communication gaps between these regions, Zahn and his colleagues reported Monday (June 4) in the journal Archives of General Psychiatry. Importantly, once-depressed participants didn't notice feeling any differently when they read the guilt and indignation sentences, suggesting that this breakdown in communication is not felt consciously.

The researchers can't yet say if pre-existing brain problems cause the communication breakdown, or if the depression itself causes this troubling pattern. Fortunately, Zahn said, the coupling of the SCSR and the anterior temporal lobe is known to be influenced by learning.

"It's likely to be the sign of something that happened because of learned experiences, plus, of course, biology," Zahn said.

That means there is hope that people prone to depression could learn to overcome their guilty tendencies. Zahn and his colleagues are now collaborating with Jorge Moll, a scientist at the D'Or Institute for Research and Education in Rio de Janeiro, to try to train people's brains. The researchers are developing a program that will allow people to watch their brain activities in real time. If it works, patients will see their brain activation change as they try to alter their emotions. That feedback is important, given that once-depressed participants don't consciously realize that they're turning social molehills into mountains of self-blame.

"It's something in the brain activation that you don't have conscious access to," Zahn said.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.