Why a DIY Pioneer Dislikes 3D Printing

NEW YORK — The DIY enthusiasts involved in today's "maker movement" love experimenting with 3D printers to turn digital designs into real-life objects made of plastic, metal, even chocolate. But one of the leading do-it-yourself pioneers has come forth to explain why he really dislikes the 3D printing craze and sees it as just a steppingstone to something greater.

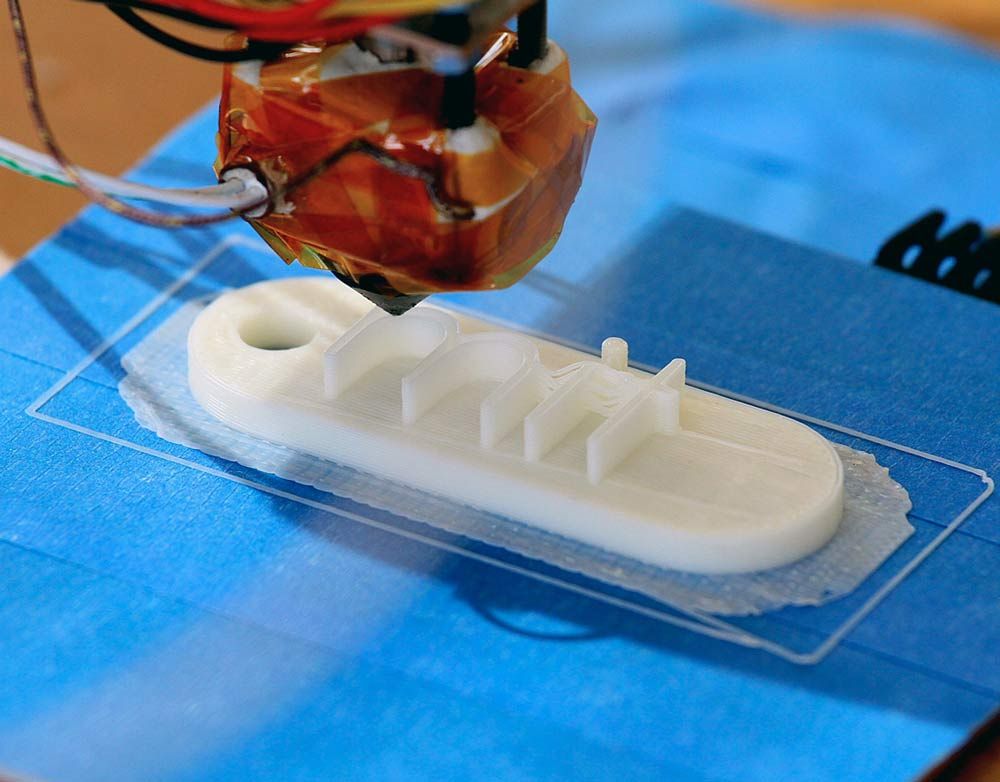

Modern 3D printers use lasers or squirt hot materials to build objects layer by layer from a computer design. They represent the latest in a long line of computer-controlled tools dating back to the 1950s — a more refined way of "metal bashing metal, squirt squirt," said Neil Gershenfeld, director of MIT's Center for Bits and Atoms.

"The real revolution in digital fabrication isn't a computer connected to a machine — that's decades old," Gershenfeld said. Instead, the revolution would be "putting the information into the material itself."

The road to "Star Trek"

Computer-controlled machines marked the first stage of "a road map to a "Star Trek" replicator where you make molecular assemblers that can make anything," Gershenfeld explained at the World Science Festival's "Innovation Square" event June 2 in Brooklyn.

The second stage, he said, involved machines making machines. The third stage has computer codes serving as a blueprint for real-world materials made from building-block components.

But Gershenfeld wants to reach the fourth and final stage: programming materials to make them intelligent. Imagine smart plastic or metal parts with the capabilities of DNA.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The last stage is we're actually making materials that themselves are programmable so that the materials can change shape in the same way biology does it, but we're doing it with materials that biology can't do," Gershenfeld said.

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology physicist has done much toward making that DIY future a reality. He founded the global Fab Lab network with field labs in locations such as Afghanistan and the Arctic Circle. He also owns "just about every known 3D printer" as head of MIT's Center for Bits and Atoms (a spinoff of the university's popular Media Lab). [US Ready to Bet $60 Million on 3D Printing]

What's wrong with DIY

Gershenfeld had more on his mind than the limitations of 3D printing — he also took the opportunity to critique the do-it-yourself movement. "I love the maker movement," Gershenfeld told the World Science Festival audience. "What I want to do is talk about what's wrong with it."

DIY enthusiasts could do better in learning from the past without rediscovering bad ways to solve problems, Gershenfeld said. He wants people to look beyond basic tools such as the popular Arduino microcontrollers that serve as tiny computers — he pointed out that the Arduinos use an Atmel AVR processor that exists separately in many cheaper varieties.

But the popularity of imperfect tools such as 3D printers or Arduinos can still do well for the DIY movement if they spur enthusiasm among more people. "I'm a big fan of bad standards at the right time," Gershenfeld said.

Making a better reality

So can the world combine the maker movement's enthusiasm with a smarter blueprint for getting things done? Gershenfeld's Fab Lab network has come up with a Fab Academy program to teach students around the world in work groups with mentors. Rather than just DIY, it's do-it-together.

Similar approaches already exist in universities including MIT, but Gershenfeld hopes to scale the learning opportunity up beyond just a few thousand MIT students. That is where long-distance learning through online education can combine with real-world teams of students and mentors.

"What's wrong with DIY is if you do it by yourself, it's easy to do dumb things," Gershenfeld said. "If you learn with other people, you can do it better. A place like MIT is organized but it doesn't scale. We want to scale to a few billion people on the planet and harness the enthusiasm of the maker movement, but don't want to reinvent dumb things."

This story was provided by InnovationNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow InnovationNewsDaily Senior Writer Jeremy Hsu on Twitter @ScienceHsu. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.