Why Do We Have Personal Space?

Thou shall not transgress thy neighbor's personal space. It's among the most sacrosanct rules of social behavior. But how do these invisible bubbles of space surrounding each of us come to exist in the first place, and why does it feel so icky when they overlap?

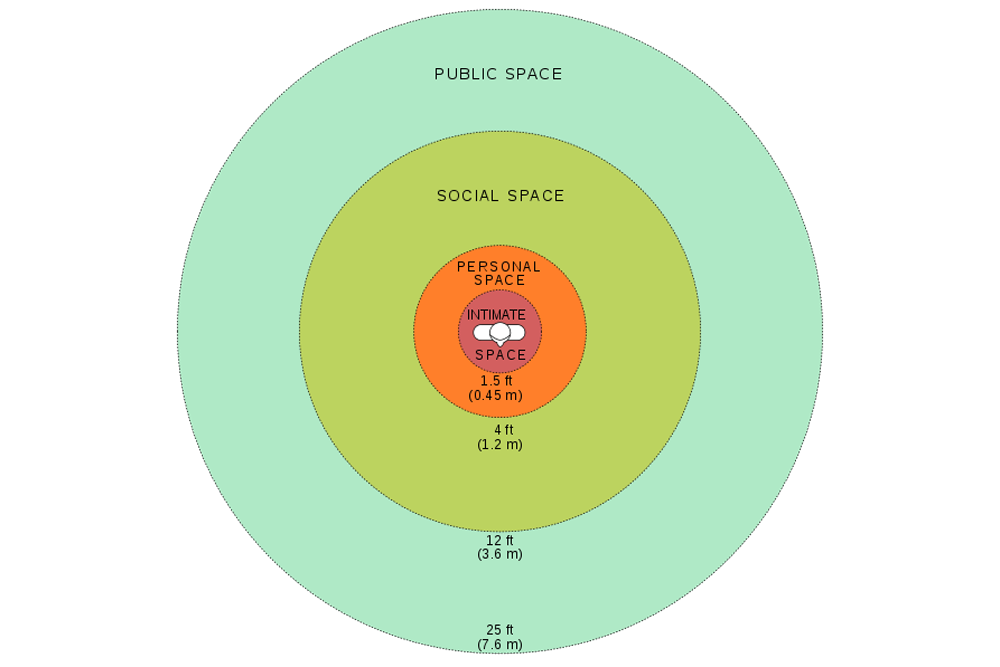

First, how big are these bubbles? According to the American anthropologist Edward Hall, whose 1960s research on the topic still stands today, you're actually enveloped by bubbles of four different sizes, each of which applies to a different set of potential interlopers.

The smallest zone, called "intimate space," extends outward from our bodies 18 inches in every direction, and only family, pets and one's closest friends may enter. A mere acquaintance hanging out in our intimate space gives us the heebie-jeebies. Next in size is the bubble Hall called "personal space," extending from 1.5 feet to 4 feet away. Friends and acquaintances can comfortably occupy this zone, especially during informal conversations, but strangers are strictly forbidden. Extending from 4 to 12 feet away from us is social space, in which people feel comfortable conducting routine social interactions with new acquaintances or total strangers. Beyond that is public space, open to all.

Those are the average sizes of Americans' personal bubbles, anyway. According to Ralph Adolphs, professor of psychology and neuroscience at the California Institute of Technology, "It is important to keep in mind that personal space of course varies depending on culture and context, and that there are significant individual differences — so these numbers should just be taken to reflect the average." [Infographic: A Day in the Life of the Average American]

As we all know, cultural or individual differences in personal bubble diameters are all too often the cause of discomfort. (Take one step back, foreigners.)

But how do these personal bubbles arise? According to Adolphs, we begin to develop our individual sense of personal space around age 3 or 4, and the sizes of our bubbles cement themselves by adolescence. In research published in the journal Nature in 2009, Adolphs and his colleagues determined that the bubbles are constructed and monitored by the amygdala, the brain region involved in fear.

"The amygdala is activated when you invade people's personal space," he told Life's Little Mysteries. "This probably reflects the strong emotional response when somebody gets too close to us. We confirmed this in a rare patient with lesions to this brain structure: she felt entirely comfortable no matter how close somebody got to her, and had no apparent personal space."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Futhermore, he said, abnormal development of the amygdala may also explain why people with autism have difficulties maintaining a normal social distance to other people.

There are times when personal space intrusions are simply unavoidable, such as in a crowded subway car. How do we cope? The psychologist Robert Sommer suggested we do it by temporarily dehumanizing those around us, avoiding eye contact and pretending they're inanimate until the moment comes when we spot an escape route. After all, it's not uncomfortable to stand inches from a wall.

This story was provided by Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover. Follow Life's Little Mysteries on Twitter @llmysteries, then join us on Facebook & Google+.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.