'Flying Saucers' Around Saturn Explained

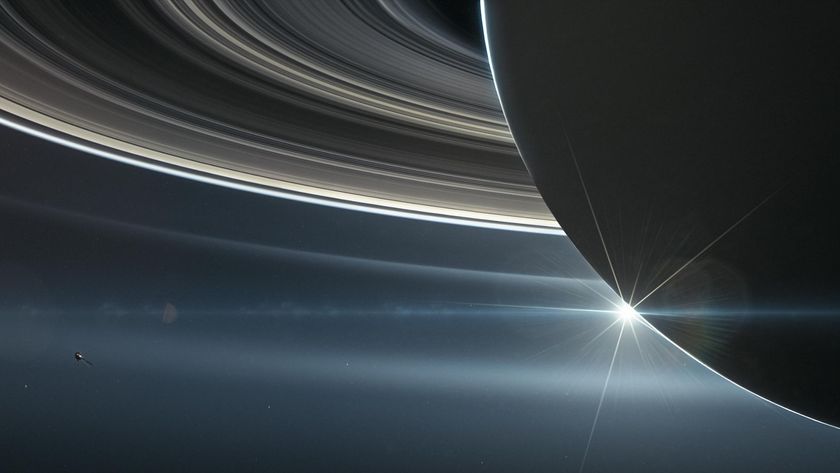

The formation of strange flying-saucer-shaped moons embedded in Saturn's rings have baffled scientists. New findings suggest they're born largely from clumps of icy particles in the rings themselves, an insight that could shed light on how Earth and other planets coalesced from the disk of matter that once surrounded our newborn sun.

Saturn's rings orbit the planet in a flat disk that corresponds to the planet's equator. Likewise, Earth and the other planets orbit the sun in a fairly flat plane that relates to the sun's equator. The planets, at least the rocky ones, are thought to have formed when bits of material orbiting the newborn sun stuck together, forming larger and larger objects that collided and coalesced.

Observations by NASA's Cassini spacecraft revealed the Saturnian moons Atlas and Pan, each roughly 12 miles (20 kilometers) from pole to pole, have massive ridges bulging from their equators some 3.7 to 6.5 miles (6 to 10.5 kilometers) high, giving them the flying-saucer appearance.

In principle, fast rates of spin might have stretched Atlas and Pan out into such unusual shapes, just as tossing a disk of pizza dough flattens it out. But neither moon whirls very quickly, each taking about 14 hours to complete a rotation. Earth, far bigger, rotates in 24 hours, of course.

Carolyn Porco, a planetary scientist at the Space Science Institute in Boulder, Colo., and her colleagues suspected these peculiar moons could be formed mostly from Saturn's rings, rather than just from fragments produced in collisions of larger moons, as some have suggested. The location of the ridges lined up precisely with the rings of icy particles in which they were embedded, findings which are detailed in the Dec. 6 issue of the journal Science.

After analyzing the shapes and densities of the moons from data captured by Cassini, Porco's team now finds Pan and Atlas appear to be mostly light, porous, icy bodies, just like the particles making up the rings. Computer simulations suggest one-half to two-thirds of these bizarre moons are made of ring material, piled up on massive, dense fragments of bigger moons that disintegrated billions of years ago after catastrophic collisions with one another.

These findings could shed light on the behavior of "accretion disks"—disks that build up as matter falls toward a gravitational pull.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Accretion disks are found everywhere in the universe—around black holes, around stars, around Jupiter," said astrophysicist Sebastien Charnoz at University of Paris Diderot in France. He is the lead author of a related new study—also described in the Dec. 6 issue of Science—that shows how the Saturnian ice-clump moons elongated and bulged out into the flying-saucer shapes.

Understanding how the icy particles piled up to make these shapes could shed light on how matter in the protoplanetary disk that accreted around our newborn sun could have clumped together to make planets, Charnoz added.