Mammoths Wiped Out By Multiple Killers

Woolly mammoths were apparently driven to extinction by a multitude of culprits, with climate change, human hunters and shifting habitats all playing a part in the long decline of these giants, researchers say.

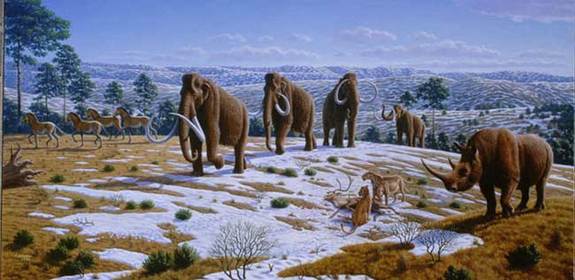

Woolly mammoths (Mammuthus primigenius) wandered the planet for about 250,000 years, ranging from Europe to Asia to North America covered in hair up to 20 inches (50 centimeters) long and possessing curved tusks up to 16 feet (4.9 meters) long. Nearly all of these giants vanished from Siberia by about 10,000 years ago, although dwarf mammoths survived on Wrangel Island in the Arctic Ocean until 3,700 years ago.

Scientists have often speculated over what might have driven the mammoths to extinction. For instance, for years researchers suspected that ancient human tribes hunted the mammoths and other ice age giants to oblivion. Others have suggested that a meteor strike might have drastically altered the climate in North America about 12,900 years ago, wiping out most of the large mammals there, the so-called "Younger Dryas impact hypothesis."

Now an analysis of thousands of fossils, artifacts and environmental sites spanning millennia suggest that no one killer is to blame for the demise of the woolly mammoths.

"These findings pretty much dispel the idea of any one factor, any one event, as dooming the mammoths," researcher Glen MacDonald, a geographer at the University of California, Los Angeles, told LiveScience.

Mammoth database

Scientists investigated the extinction of woolly mammoths living in Beringia, the last refuge of mammoths that nowadays lies mostly submerged under the icy waters of the Bering Strait. To get an idea of woolly mammoth abundance, past climate and other environmental factors, they analyzed samples from more than 1,300 woolly mammoths, nearly 450 pieces of wood, nearly 600 archaeological sites and more than 650 peatlands, compiling their ages and locations to see how these giants and their environments changed over time. They also probed mammoth genetic data found in fossils of the titans.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"There will be people talking about the incompleteness of the fossil record, and there'll always be uncertainties here, no question, but the size of our database is thousands of data points, so I think we can see the general patterns," MacDonald said.

Their results revealed woolly mammoths flourished in the open steppe of Beringia between 30,000 to 45,000 years ago, with its relatively abundant grass and willow trees. The area wasn't as warm then as today, but not as cold as the height of the ice age. "That seemed to be very favorable for mammoths, in terms of abundance," MacDonald said. Humans coexisted with mammoths back then, clearly not driving them to extinction at that time. [Gallery: The World's Biggest Beasts]

Later, during the iciest part of the ice age 20,000 to 25,000 years ago, the "Last Glacial Maximum," northern woolly mammoth populations declined, likely because the area became too barren to be hospitable. However, during that time, the giants became abundant in the warmer interior parts of Siberia.

"There was an old idea that cold glacial conditions like the Last Glacial Maximum were optimal for mammoths," MacDonald said. "That idea now doesn't really hold water."

Northern refuge

Northern mammoth populations grew after the Last Glacial Maximum, but then dipped again during the Younger Dryas period about 12,900 years ago. Although there is controversy as to what happened at that time, "there was certainly a very rapid and profound cooling of many regions then, followed by rapid warming," MacDonald said. "Did this cause the extinction of the mammoth? Absolutely not. They were still present in far northern sites at the end of the Younger Dryas. Right now it's not quite definitive how great an impact the Younger Dryas had."

The last mammoths seen on the continents were concentrated in the north. They apparently disappeared about 10,000 years ago as the climate warmed and peatlands, wet tundra and coniferous forests developed, environments to which mammoths were poorly suited. The long-lasting proximity between mammoths and humans suggested that our species was perhaps a factor in the beasts' decline, possibly killing off the final island populations of woolly mammoths that went extinct 3,700 years ago.

Overall, these findings suggest the mammoths experienced a long decline due to many factors.

"There was no one event that ended the mammoths," MacDonald said. "It was really the coalescence of climate changeand the habitat change that triggered [it], and also human predators on the landscape at the end."

These findings regarding mammoths could shed light on what species today might face in the future. [10 Species You Can Kiss Goodbye]

"Mammoths faced profound climate change and very profound changes in their habitat and landscape, and also faced pressure from humans," MacDonald said. "Now think about the 21st century, where we're seeing rapid climate change, massive changes in the landscape and certainly pressure from humans on the environment. Species today are facing the same sorts of challenges the mammoths did, but the rate of those changes today are much greater than what mammoths faced."

Future research can focus on other animals once plentiful across Beringia, such as horse and bison. The scientists detailed their findings online June 12 in the journal Nature Communications.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.