Massive Solar Flare in March Broke Sun Storm Record

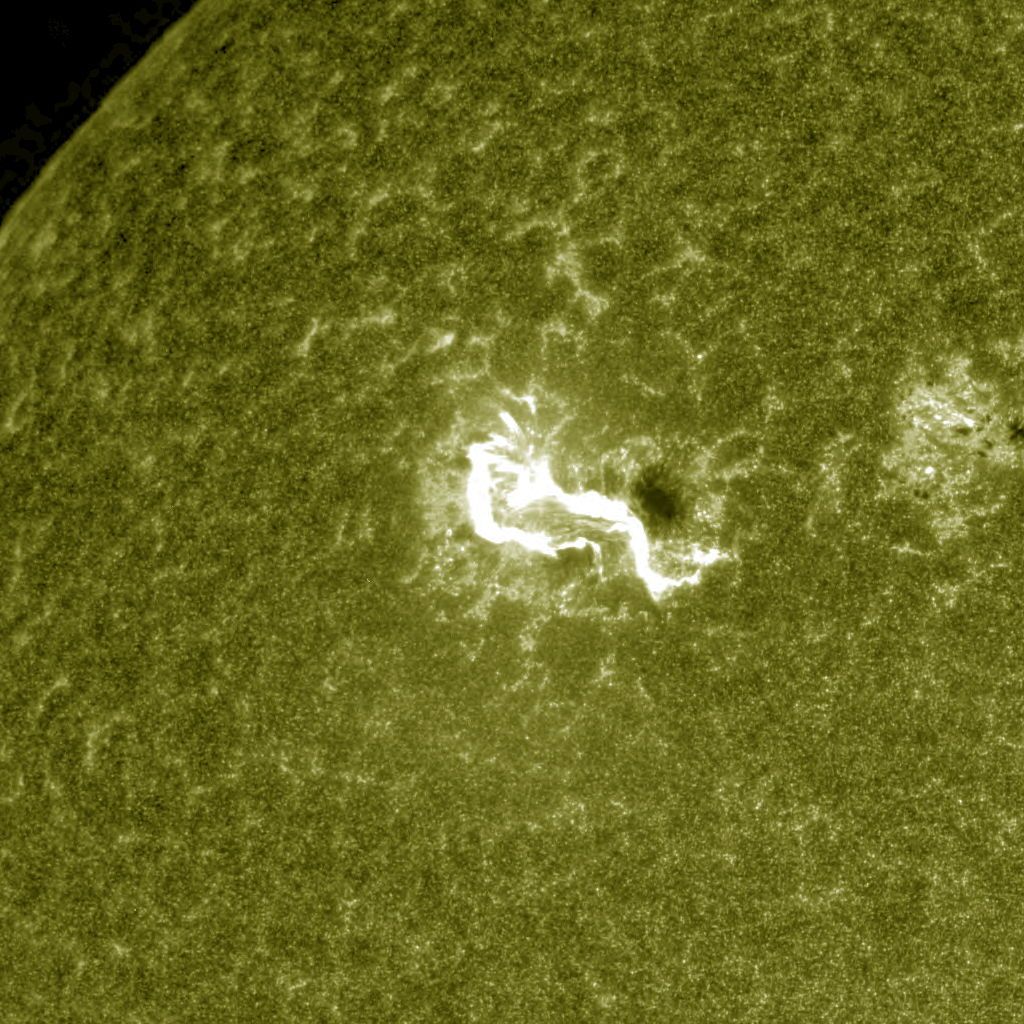

ANCHORAGE, Alaska — A massive flare that exploded from the solar surface in March unleashed the highest-energy light ever seen during a sun eruption, scientists say.

On March 7, the sun let loose a massive X5.4 solar flare during its biggest outburst in five years. NASA's Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope saw an unusually long-lasting pulse of gamma rays — a form of light with even greater energies than X-rays — produced by the flare.

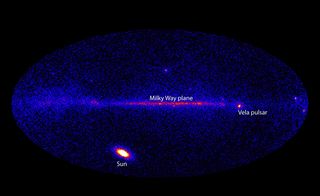

At the flare's peak, the gamma rays that were emitted from the sun were 2 billion times more energetic than visible light, making it a record-setting detection during or immediately after any previously seen solar flare, researchers said. In fact, as the flare erupted, the sun briefly became the brightest object in the gamma-ray sky.

"The sun is [usually] not a very bright source in gamma rays," said Nicola Omodei, an astrophysicist at Stanford University in California. "We don't detect the sun on a daily basis. On the other hand, on March 7, the sky looked completely different, as the sun became an intense, bright source of high-energy gamma rays." [The Sun's Wrath: Worst Solar Storms in History]

Omodei presented the findings Monday (June 11) here at the 220th meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

Long and intense eruption

In addition to the intensity of the gamma-ray emissions, astronomers were surprised by the outburst's length. Fermi's Large Area Telescope (LAT) observed high-energy gamma rays for approximately 20 hours, which is 2 1/2 times longer than any event ever recorded, Omodei said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Fermi's observations also enabled astronomers to pinpoint the source of the gamma rays on the sun's disk, making it the first time that such a feat has been accomplished for a gamma-ray source with energies beyond 100 million electron volts (MeV), researchers said.

"Thanks to the LAT's improved angular resolution, [we're] able to localize the region of the high-energy gamma ray emission," Omodei said. "The location of the high-energy gamma rays is consistent with the region of the X-ray flare."

Solar flares and other emissions from the sun produce gamma rays by accelerating charged particles, which then collide and interact with matter in the sun's atmosphere and visible surface.

Learning about solar flares

Fermi's LAT combs the sky for highly energetic gamma rays every three hours. This instrument, along with Fermi's Gamma-ray Burst Monitor (GBM), detected a strong but less powerful solar flare on June 12, 2010, scientists said.

"Seeing the rise and fall of this brief flare in both instruments allowed us to determine that some of these particles were accelerated to two-thirds of the speed of light in as little as three seconds," Michael Briggs, a member of the GBM team at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, said in a statement.

The sun's activity waxes and wanes on a roughly 11-year cycle. Currently, the sun is ramping up in its current Solar Cycle 24 toward an expected activity maximum in mid-2013.

"As the solar cycle progresses toward maximum, new Fermi observations of solar flares will help us in understanding how flares accelerate particles and where gamma rays are produced," Omodei said.

The highly sensitive LAT, with its wide field of view, makes Fermi a valuable tool for observing the sun, researchers said, and could revolutionize the field of solar physics.

"Merged with available theoretical models, Fermi observations will give us the ability to reconstruct the energies and types of particles that interact with the sun during flares, an understanding that will open up whole new avenues in solar research," Gerald Share, an astrophysicist at the University of Maryland in College Park, said in a statement.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.