Cyborg Fuel Cell Powered by Brain Fluids

Cockroaches, snails and clams have already become living batteries as experimental cyborgs. A new MIT fuel cell could extend that futuristic idea to humans by drawing its power from the fluid surrounding the human brain.

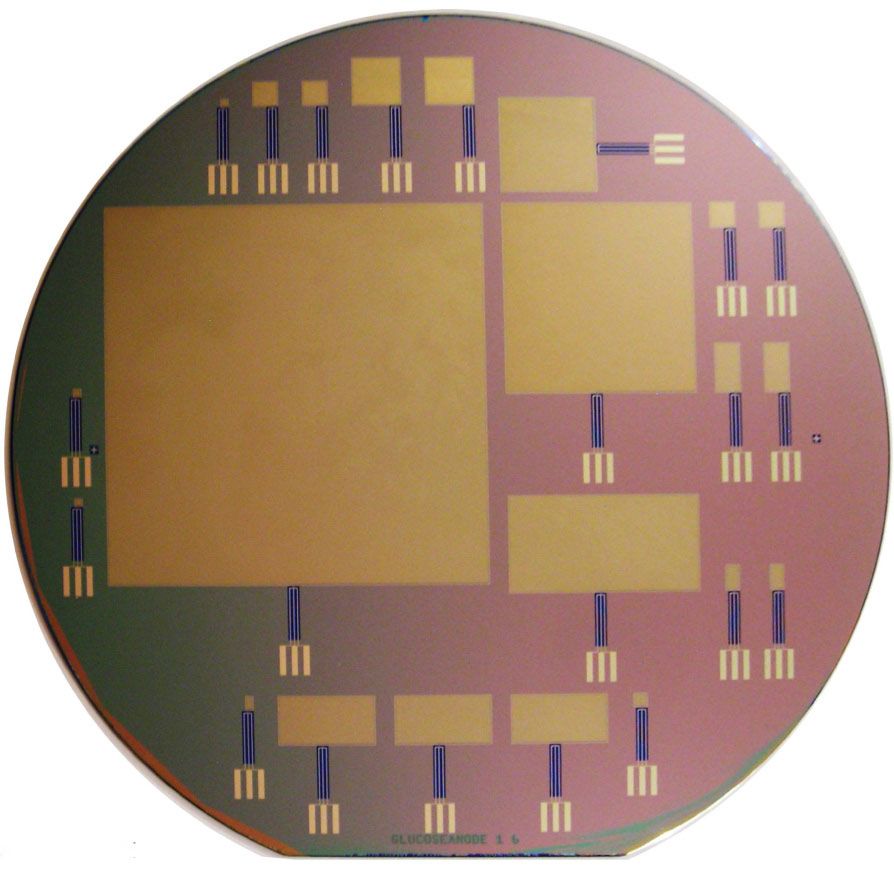

The fuel cell can already make enough power for low-power brain implants — devices that could eventually help paralyzed patients move their legs and arms again. MIT researchers made the fuel cell out of silicon and platinum so that it can last for years with a low risk of provoking the body's immune response.

"The glucose fuel cell, when combined with such ultra-low-power electronics, can enable brain implants or other implants to be completely self-powered," said Rahul Sarpeshkar, an associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science at MIT.

MIT's fuel cell mimics the role of the human body's enzymes by breaking down glucose sugar into energy. The glucose in the brain's cerebrospinal fluid represents a continuous fuel supply for the fuel cell — even if the fuel cell currently generates just hundreds of microwatts (one microwatt is equal to one millionth of a watt).

Scientists had already shown they could power a heart pacemaker with glucose fuel cells in the 1970s, but they gave up on the idea because such fuel cells used biological enzymes that eventually wore out. MIT's fuel cell avoids that problem by relying on nonbiological materials. [Cyborg Snail Turned into Living Battery]

"It's a proof of concept that they can generate enough power to meet the requirements," said Karim Oweiss, an associate professor of electrical engineering, computer science and neuroscience at Michigan State University.

A next step for MIT involves showing how well the fuel cell works in living animals, Oweiss said. Other researchers have already shown how small creatures such as cyborg clams and cyborg snails can refuel implanted fuel cells with their own bodies.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Sarpeshkar's MIT lab previously worked on implantable devices that bridge the gap between brain and machine — recording and decoding nerve signals, stimulating nerves, or communicating wirelessly with brain implants. But medical implants capable of harvesting energy from a person's own bodily fluids remain years away.

"It will be a few more years into the future before you see people with spinal-cord injuries receive such implantable systems in the context of standard medical care, but those are the sorts of devices you could envision powering from a glucose-based fuel cell," said Benjamin Rapoport, a former graduate student in the Sarpeshkar lab and the first author on the new MIT study.

The study is detailed in the June 12 online edition of the journal PLoS One.

This story was provided by InnovationNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.