Small, rocky planets can coalesce around a wide variety of stars, suggesting that Earth-like alien worlds may have formed early and often throughout our Milky Way galaxy's history, a new study reveals.

Astronomers had previously noticed that huge, Jupiter-like exoplanets tend to be found around stars with high concentrations of so-called "metals" — elements heavier than hydrogen and helium. But smaller, terrestrial alien planets show no such loyalty to metal-rich stars, the new study found.

"Small planets could be widespread in our galaxy, because they do not require a high content of heavy elements to form," said study lead author Lars Buchhave, of the University of Copenhagen in Denmark.

A diversity of stars

Buchhave and his colleagues analyzed data from NASA's planet-hunting Kepler space telescope, which has been continuously observing more than 150,000 stars since its launch in March 2009.

Kepler watches those stars for tiny brightness dips, some of which are caused by alien planets that cross the stars' faces from the telescope's perspective. To date, Kepler has flagged more than 2,300 exoplanet candidates. While just a small fraction have been confirmed, Kepler scientists estimate that at least 80 percent will end up being the real deal. [Gallery: A World of Kepler Planets]

In the new study, the researchers looked at Kepler observations of 226 planet candidates circling 152 different stars. More than three-quarters of these potential planets are smaller than Neptune — i.e., their diameters are less than four times that of Earth — and some of them are as diminutive as our own planet, researchers said.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The astronomers studied the stars' spectra and found that small, rocky worlds circle stars with a much broader range of metal content than do giant planets.

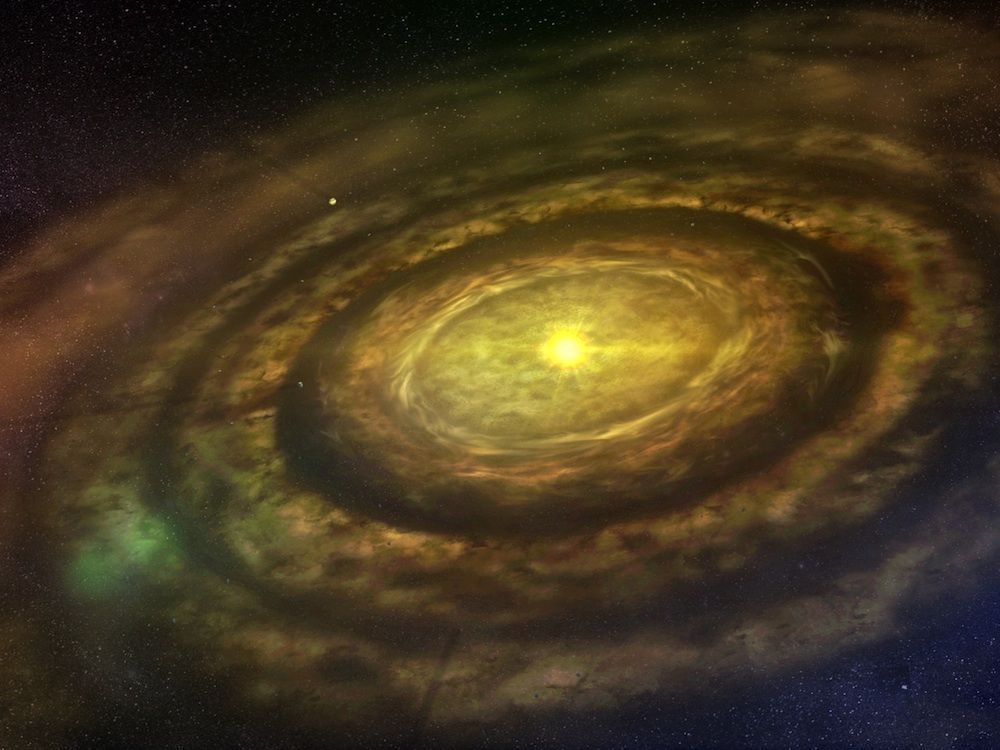

"Naively, one might think that the more material you have in the [protoplanetary] disk, the more likely you are to form (small) planets," Buchhave told SPACE.com via email. "What we see, though, is that small planets form around stars with a wide range in heavy element content, while the close-in Jupiter-type planets seem to predominantly form around stars with a higher metal content."

In fact, small, terrestrial planets can form around stars nearly four times more metal-poor than our own sun, researchers said. The results suggest that Earth-size worlds may be common throughout the Milky Way, perhaps providing many places for life to gain a foothold.

"Since small planets could be widespread in our galaxy, the chances of life developing could be higher, simply because there could be more terrestrial-sized planets where life could evolve," Buchhave said.

The team's results are published today (June 13) in the journal Nature.

Early planets, early life?

Metals weren't present at the universe's birth. Rather, they're created inside stellar cores, implying that gas giants had a hard time forming until multiple generations of stars had been born, died and spread their innards throughout the cosmos in massive supernova explosions.

But the fact that rocky planets can take shape around metal-poor stars means the first roughly Earth-like worlds may have formed long, long ago.

"This work suggests that terrestrial worlds could form at almost any time in our galaxy’s history," co-author David Latham, of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, said in a statement. "You don’t need many earlier generations of stars."

Our solar system has been around for 4.6 billion years, and the earliest signs of life on Earth date from about 3.8 billion years ago. But the new study suggests that we may be relative latecomers as far as Milky Way biology goes.

"Knowing that the formation of rocky planets can occur in environments of lower metallicity than those of gas giants implies that there could be some places in the universe where rocky planets and life got an earlier start than did Earthlings," Debra Fischer, an astronomer at Yale University, wrote in a commentary accompanying the study in the same issue of Nature.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.