Materials Mysteriously Emit Electric Signal Before Failing

Electrical signals given off by white flour could shed light on warning signs emitted by common materials before they fail in the face of earthquakes, bridge collapses and engine breakdowns, researchers say.

At the same time, these findings deepen the mystery of why shifting powders might generate electricity in the first place, investigators added.

Scientists have long known that sudden failures of crystals, glasses and other materials can produce tiny electrical sparks. Centuries of anecdotal evidence also suggest that electrical disturbances sometimes precede major earthquakes. However, the underlying mechanisms of all these signals remain highly uncertain.

To learn more about these electrical signals, researchers investigated so-called "cohesive powders" — materials composed of tiny grains stuck together. These powders are notoriously unpredictable, as the bonds between grains can loosen with catastrophic effects, such as enlarging hairline fractures in ceramic machine parts or weakening rocks that keep faults in the earth from shifting and causing earthquakes.

[Cyborg Snail Turned Into Living Battery]

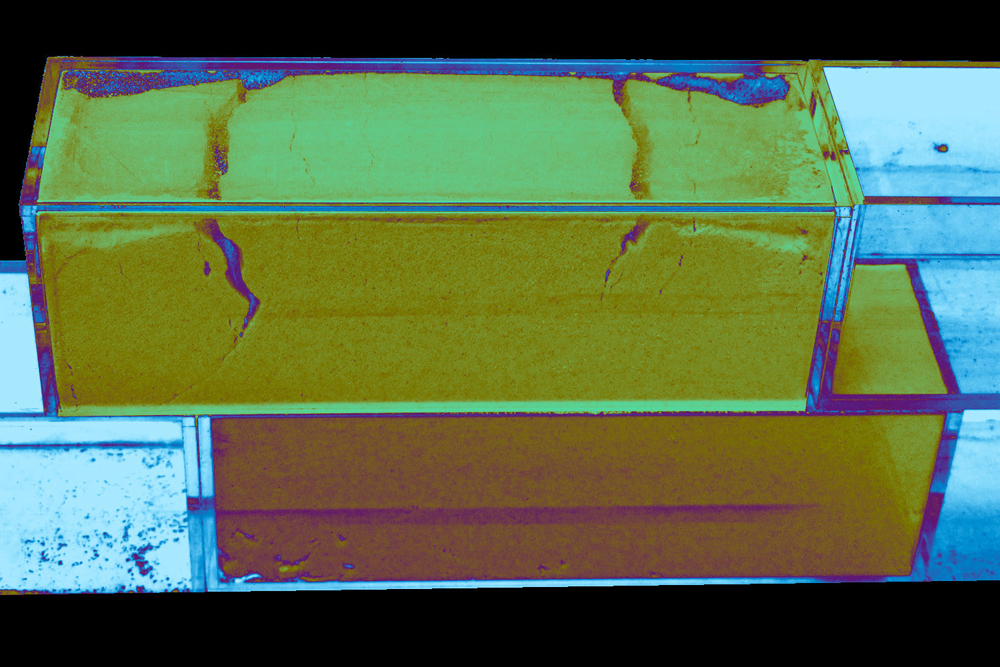

Experiments involving avalanches of powders such as white flour within rolling cylinders and tipping boxes revealed unexpected changes in voltage a few seconds before the collapse. The scientists also found that voltage spikes occurred when crack-like defects opened and closed in powder beds.

"It is really extremely surprising to me that hundreds of volts are produced by disturbing common kitchen flour," said researcher Troy Shinbrot, a physicist at Rutgers University in Piscataway, N.J. "It is also surprising both that this has never been reported before and that its cause is entirely mysterious. If we hadn't measured this in several different ways and failed to rule out any spurious effect that we could come up with, I would remain highly dubious of the effect."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers suggest that analyzing voltage spikes in real-life situations might reveal signs of large-scale breakdowns well before they occur.

"Ceramics are made entirely of powders, so a natural question is whether defect formation in ceramics may be detectable, and so whether advance warning of impending failure can be achieved," Shinbrot said.

What causes these voltage changes remains unknown. The materials tested are not piezoelectric — that is, they do not convert mechanical energy into electrical charge. They also do not appear to be experiencing chemical changes that might lead to measurable voltages.

"The root cause of the effects that we report remain mysterious," Shinbrot told InnovationNewsDaily. "Perhaps these effects are due to some trivial effect that we have overlooked, but after searching with multiple researchers in several experiments using different materials for over two years, we failed to find the cause. Experiments to uncover what is going on at a microscopic level leading to luminous or voltage effects would be very exciting."

As to whether these findings might explain electrical and light phenomena linked with earthquakes, Shinbrot cautioned that quakes are much more complex than simple powders. Nevertheless, there is a long history of lab-scale experiments of rocks and grains shedding light on earthquakes, landslides, rock bursts and other geological activity. Hopefully, understanding what happens with powders "may tell us about what is going on under the ground," he said.

The scientists detailed their findings online June 11 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

This story was provided by InnovationNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience.