Mysterious Bones May Belong to John the Baptist

A small handful of bones found in an ancient church in Bulgaria may belong to John the Baptist, the biblical figure said to have baptized Jesus.

There's no way to be sure, of course, as there are no confirmed pieces of John the Baptist to compare to the fragments of bone. But the sarcophagus holding the bones was found near a second box bearing the name of St. John and his feast date (also called a holy day) of June 24. Now, new radiocarbon dating of the collagen in one of the bones pegs its age to the early first century, consistent with the New Testament and Jewish histories of John the Baptist's life.

"We got some dates that are very interesting indeed," study researcher Thomas Higham of the University of Oxford told LiveScience. "They suggest that the human bone is all from the same person, it's from a male, and it has a very high likelihood of an origin in the Near East," or Middle East where John the Baptist would have lived.

Mysterious bone box

The bones were found in 2010 by Bulgarian archaeologists Kazimir Popkonstantinov and Rossina Kostova while excavating an old church site on the island of Sveti Ivan, which translates to St. John. The church was constructed in two periods in the fifth and sixth centuries.

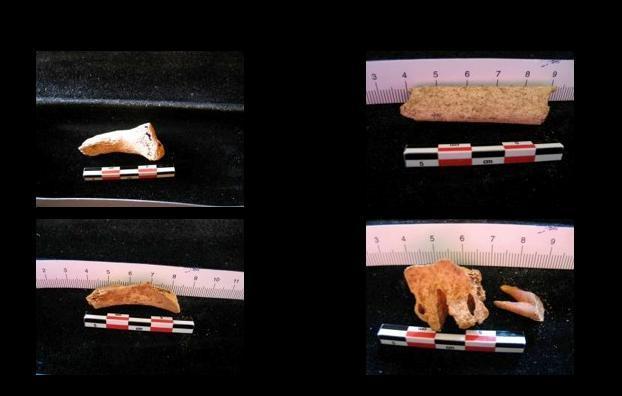

Beneath the altar, the archaeologists found a small marble sarcophagus, about 6 inches (15 centimeters) long. Inside were six human bones and three animal bones. The next day, the researchers found a second box just 20 inches (50 cm) away. This one was made of volcanic rock called tuff. On it, an inscription read, "Dear Lord, please help your servant Thomas" along with St. John the Baptist's name and official church feast day.

A grotesque gift

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The findings paint a story of a man named Thomas charged with bringing relics, or body parts, of St. John to the island to consecrate a new church there. It was common in the fourth and fifth centuries for wealthy patrons to pay for new churches and to gift saintly relics to the monks who staffed them, Higham told LiveScience. [8 Alleged Relics of Jesus]

"We can imagine that the construction of this church was predicated on the basis of this very important gift, perhaps from the patron to the monastery," Higham said.

The human bones in the box included a knucklebone, a tooth, part of a cranium, a rib and an ulna, or arm bone. The researchers could only date the knucklebone, because radiocarbon dating relies on organic material, and only that bone had enough collagen for a good analysis. The researchers were able to reconstruct DNA sequences from three of the bones, however, showing them to be from the same person, likely a Middle Eastern man.

"Our worry was that the remains might have been contaminated with modern DNA," study researcher Hannes Schroeder, formerly of Oxford, said in a statement. "However, the DNA we found in the samples showed damage patterns that are characteristic of ancient DNA, which gave us confidence in the results. Further, it seems somewhat unlikely that all three samples would yield the same sequence considering that they had probably been handled by different people."

Schroeder added that "both of these facts suggest that the DNA we sequenced was actually authentic."

Strangely, the three animal bones (one from a sheep, one from a cow, and one from a horse), were all about 400 years older than the human bones in the reliquary. Those three bones all seem to come from the same time and location, Higham said. They may have been placed there as a way to desecrate the human bones, he said. Or someone may have just been trying to make the bone box look a little more impressive.

"It is very curious," Higham said. [8 Grisly Archaeological Discoveries ]

Elusive identification

Historical research by Oxford professor Georges Kazan suggests that relics supposedly from John the Baptist were on the move out of Jerusalem by the fourth century. Many of these artifacts were shuttled through the ancient city of Constantinople and may well have been gifted to the Sveti Ivan monastery from there.

None of this proves that the bones belonged to a historical figure named John the Baptist, but researchers haven't been able to rule out the possibility, Higham said. Their study has not yet been published in a peer-reviewed journal, but a program detailing the research will be aired on the United Kingdom National Geographic Channel on Sunday (June 17). National Geographic funded the research.

Even if the monks of Sveti Ivan believed the bones to be St. John's, they may not have been. Fake relics were and still are common. For example, at least 30 nails have been venerated as the ones used to keep Jesus Christ on the cross (biblical scholars debate whether three or four nails would have been used). Likewise, French theologian John Calvin once noted that if all of the supposed fragments of Jesus' cross were gathered together, they'd fill a shipload. Even Joan of Arc has been the subject of forgery. A 2007 study found that alleged pieces of her body kept in a French church actually belonged to an Egyptian mummy. [9 Famous Art Forgers]

The Sveti Ivan box is not the only reliquary said to hold the remains of John the Baptist, Higham said. If the researchers are able to test other bones said to be the saint's, they could build a circumstantial case for their authenticity. Nevertheless, a positive identification will likely remain out of reach.

"Definitely proving it, I think, is going to remain ever-elusive," Higham said.

Editor's Note: This article was updated on June 15 to correct the nationality of Kazimir Popkonstantinov and Rossina Kostova. They are Bulgarian, not Romanian.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.