NASA's Juno Mission to Probe Jupiter's Biggest Secrets

ANCHORAGE, Alaska — A NASA probe that is traveling through space on its way to Jupiter is expected to help astronomers unlock mysteries about the largest planet in our solar system when it arrives there in 2016.

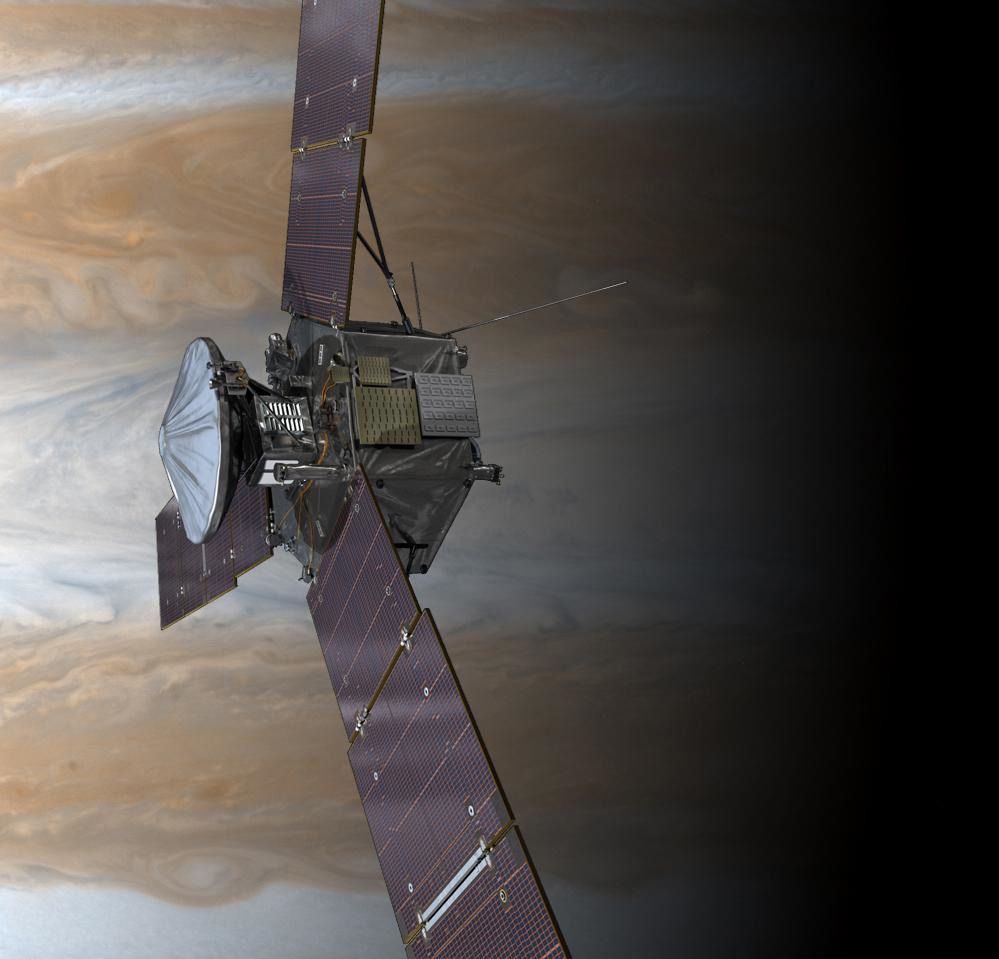

NASA's Juno mission was launched in August 2011 to study how Jupiter formed and evolved. After a five-year journey, the spacecraft is expected to arrive at the gas giant planet in August 2016.

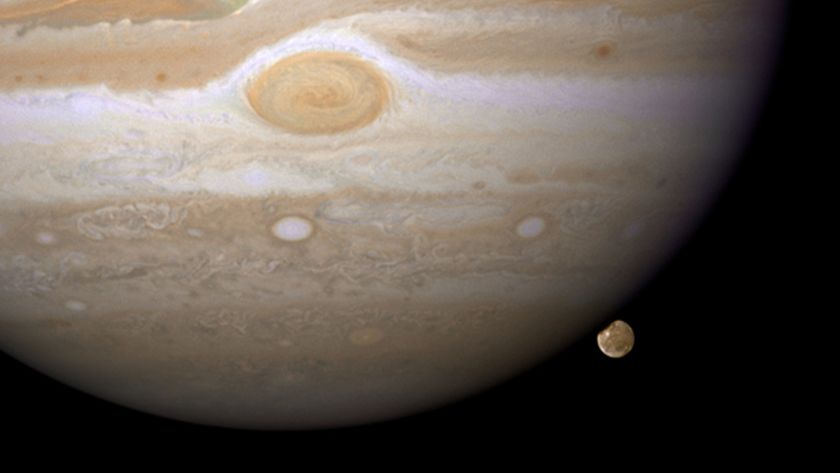

Jupiter has long intrigued astronomers, from the planet's distinct surface features and complex weather systems to its mysterious origin and evolution, said Fran Bagenal, a professor of astrophysical and planetary sciences at the University of Colorado in Boulder, and a co-investigator on the Juno mission.

"People have been looking at this exterior since the time of Galileo," she said. "[But] we know very little of what's inside. We're sending Juno out there to Jupiter to try to understand the origin and evolution of Jupiter, [to] try to explain how much water there is, what it's like inside, what the atmosphere is like."

Bagenal discussed the exciting results the Juno mission is expected to yield in a session on June 11 here at the 220th meeting of the American Astronomical Society.

Once the solar-powered Juno spacecraft is captured into orbit around Jupiter, the probe will map the planet's magnetic and gravitational fields to learn more about the interior structure of Jupiter. [Photos: NASA's Juno Mission to Jupiter]

In particular, Juno will investigate the composition of the planet's core, which could help researchers piece together how Jupiter and the rest of the solar system formed. Currently, scientists are unsure whether Jupiter has a solid core of heavy elements, or if it is made entirely of gas.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As Juno flies around Jupiter, the spacecraft's own motion will allow scientists to measure the planet's interior gravity, and these observations "will be able to tell us about the distribution of mass inside and the dynamics of material moving around on the interior," Bagenal said.

Juno will also scan Jupiter's atmosphere to determine its composition and to try to reveal how much water is locked up in the planet.

"Water absorbs microwaves," Bagenal said. "What we're going to do is look at the microwaves coming out at six different spectral bands. As we go over the belts and zones, we'll see how much is absorbed, and we intend to map out the amount of water in the planet."

In addition to being the largest planet in the solar system, Jupiter also has the most powerful magnetic field. As Juno orbits the planet, the spacecraft will examine the charged particles in Jupiter's magnetosphere.

As the probe passes over Jupiter's poles, it will also collect measurements of Jupiter's spectacular and bright auroras.

"We've never flown through these regions, and Juno will go through and explore these regions in detail," Bagenal said. "We'll be able to test our ideas of how auroras are produced on Earth in a very different system, the Jovian system."

But it won't be easy.

When it arrives at Jupiter, Juno will settle into a highly elliptical orbit to avoid the planet's high radiation belts near the equator. The spacecraft's instruments are encased in titanium to protect them from this intense radiation, but there are still hazards, Bagenal said.

"We hope to have 33 orbits around Jupiter," she said. "But eventually, the spacecraft will go through the radiation belts, and we suspect it will die."

After spending roughly a year at Jupiter, the spacecraft will eventually be de-orbited sometime in October 2017, NASA officials have said.

But while Jupiter's radiation is a constant threat, Bagenal is confident the spacecraft will perform well.

"Hopefully it'll survive," Bagenal said. "We've done our best. At this point, there's no fixing it."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.