Most Black Holes Are Cosmic Snackers Instead of Binge Eaters

Frequent snacking is more common than binge eating for black holes, a new study suggests.

Scientists observed 30 galaxies with particularly active large central black holes, and found that most of these ate their fill through regular small meals rather than a single giant feast.

Black holes, the densest objects in the universe, often lie at the centers of galaxies, and they gorge on gas dust and stars that come too close. The most active central black holes are called quasars when material falling on them releases bright light that can be seen across the universe. Astronomers had thought that many quasars were powered by single events, such as mergers with other galaxies that drove huge streams of gas and dust into their centers.

While this is sometimes the case, it seems that more commonly, quasar black holes feed on your average batch of gas or small satellite galaxy. [Video: Black Hole Eats Asteroids for Breakfast]

"The brilliant quasars born of galaxy mergers get all the attention because they are so bright and their host galaxies are so messed up," Yale University astronomer Kevin Schawinski said in a statement. "But the typical bread-and-butter quasars are actually where most of the black-hole growth is happening. They are the norm, and they don't need the drama of a collision to shine."

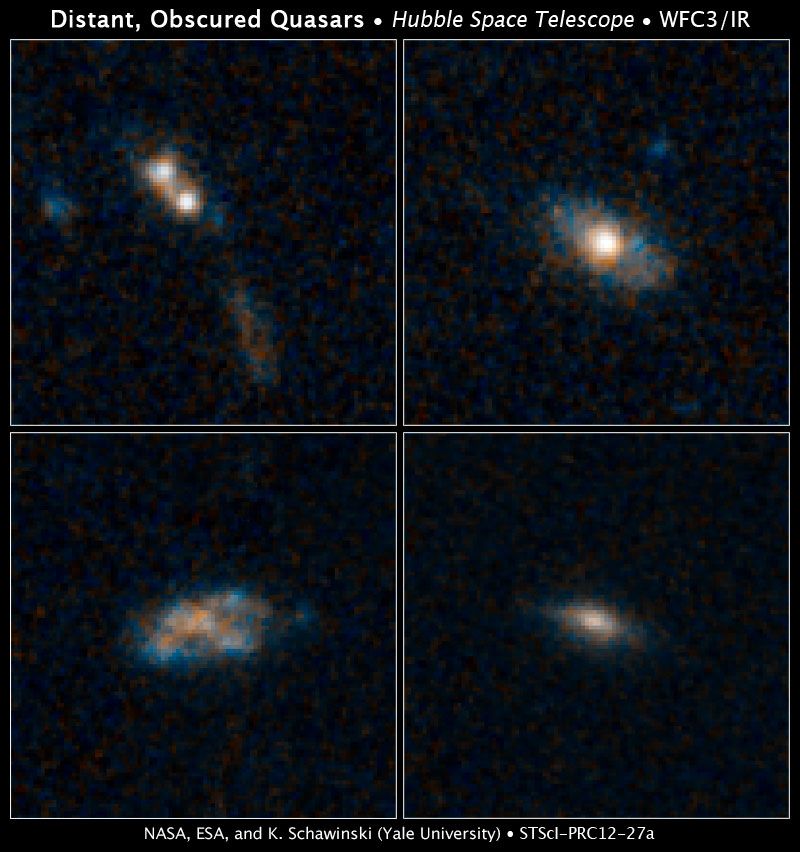

Schawinski and his colleagues observed the collection of quasars with NASA's Hubble Space Telescope and Spitzer Space Telescope, which both have the ability to look in infrared light, which pierces through the dust that often shrouds galaxies in optical light.

The researchers looked for galaxies that were exceptionally bright in infrared light, hinting that their central black holes were probably very active. They then studied these galaxies' shapes for signs that they had collided with other galaxies, which would have left their forms distorted and strange.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The astronomers found that 26 of the 30 galaxies observed bore no signs of having undergone mergers, with only one galaxy in the sample looking like it might have collided with a neighbor.

Still, even the sharp eyes of Hubble were not enough to zoom in to see what specific processes are feeding these run-of-the-mill quasars.

"I think it's a combination of processes, such as random stirring of gas, supernovae blasts, swallowing of small bodies, and streams of gas and stars feeding material into the nucleus," Schawinski said.

The researchers are hoping NASA's next major observatory project, the James Webb Space Telescope to launch in 2018, will do the trick.

"To get to the heart of what kinds of events are powering the quasars in these galaxies, we need the Webb telescope," Schawinski said. "Hubble and Spitzer have been the trailblazers for finding them."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook & Google+.