Queen of Sheba's Gift? Genetic Find Ties Ethiopia to Other Lands

The Queen of Sheba's genetic legacy may live on in Ethiopia, according to new research that finds evidence of long-ago genetic mixing between Ethiopian populations and Syrian and Israeli people.

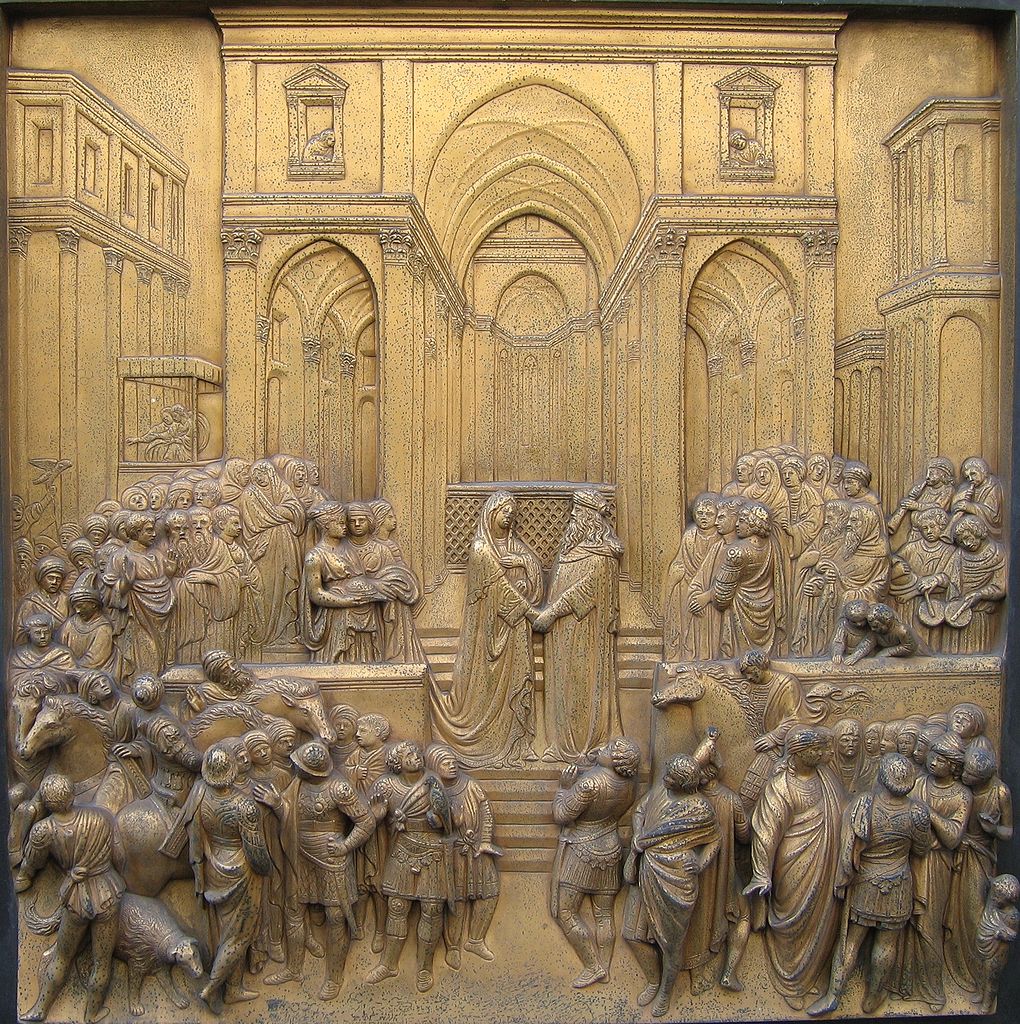

The Queen of Sheba, known in Ethiopia as Makeda, is mentioned in both the Bible and the Quran. The Bible discusses diplomatic relations between this monarch and King Solomon of Israel, but Ethiopian tradition holds that their relationship went deeper: Makeda's son, Menelik I, the first emperor of Ethiopia, is said to be Solomon's offspring.

Whether this tale is true or not, new evidence reveals close links between Ethiopia and groups outside of Africa. Some Ethiopians have 40-50 percent of their genomes that match more closely with populations outside of Africa than those within, while the rest of the genomes more closely match African populations, said study researcher Toomas Kivisild of the University of Cambridge. [History's Most Overlooked Mysteries]

"We calculated genetic distances and found that these non-African regions of the genome are closest to the populations in Egypt, Israel and Syria," Kivislid said in a statement.

From its perch on the Horn of Africa, Ethiopia is the site of early hominin discoveries such as "Lucy," a fossilized Australopithecus afarensis and an early human ancestor. Ethiopia is also a gateway between Africa and Asia, according to Kivislid and his colleagues. But few genetic studies have delved specifically into the Ethiopian genome.

Both agriculture and linguistics show a link between Ethiopia and lands outside of Africa. For example, archaeologists have uncovered wheat and barley farming in Ethiopia, agriculture that first arose in the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East. Linguistically, Ethio-Semitic, a language spoken both in Ethiopia and nearby Eritrea, has been traced to a Middle Eastern origin.

To better understand the genetic ties between Ethiopia and the rest of the world, Kivislid and his colleagues analyzed the genomes of 188 Ethiopian men from 10 diverse populations. The men came from different regions and spoke different languages.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The results revealed that the Ethiopian genome is less ancient than those of some South African populations, and that Ethiopian genes are quite diverse. Language hinted at genetics, the researchers found: Speakers of Semetic and Cushitic tongues were shown to have genomes about half comprised of genes from non-African origins. Other groups were characterized by mixes of eastern and western African genes.

Tracing the genomic changes, the researchers found that the non-African and African genes first mingled about 3,000 years ago rather than during more recent times, the researchers reported today (June 21) in the American Journal of Human Genetics. [Most Tragic Love Stories in History]

That timeline confirms what linguistic studies have suggested about links between the Middle East and Ethiopia during this time period, the researchers wrote. It also matches records and tales of the reign of the Queen of Sheba from about 1005 to 955 B.C., when trade routes were established and a royal son, perhaps, was born. Relations between the Horn of Africa and the Middle East would continue for centuries.

"These long-lasting links between the two regions are reflected in influences still apparent in the modern Ethiopian cultural, and, as we show here, genetic landscapes," the researchers wrote.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.