Stonehenge a Monument to Unity, New Theory Suggests

The mysterious structure of Stonehenge may have been built as a symbol of peace and unity, according to a new theory by British researchers.

During the monument's construction around 3000 B.C. to 2500 B.C., Britain's Neolithic people were becoming increasingly unified, said study leader Mike Parker Pearson of the University of Sheffield.

"There was a growing islandwide culture — the same styles of houses, pottery and other material forms were used from Orkney to the south coast," Parker Pearson said in a statement, referring to the Orkney Islands of northern Scotland. "This was very different to the regionalism of previous centuries."

By definition, Stonehenge would have required cooperation, Parker Pearson added.

"Stonehenge itself was a massive undertaking, requiring the labor of thousands to move stones from as far away as west Wales, shaping them and erecting them. Just the work itself, requiring everything literally to pull together, would have been an act of unification," he said. [Photos: A Walk Through Stonehenge]

The new theory, detailed in a new book by Parker Pearson, "Stonehenge: Exploring the Greatest Stone Age Mystery" (Simon & Schuster, 2012), is one of many hypotheses about the mysterious monument. Theories range from completely far-fetched (space aliens or the wizard Merlin built it!) to far more evidence-based (the monument may have been an astronomical calendar, a burial site, or both).

The Culture of Stonehenge

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Along with fellow researchers on the Stonehenge riverside Project, Parker Pearson worked to put Stonehenge in context, studying not just the monument but also the culture that created it.

What they found was evidence of a civilization transitioning from regionalism to a more integrated culture. Nevertheless, Britain's Stone Age people were isolated from the rest of Europe and didn't interact with anyone across the English Channel, Parker Pearson said.

"Stonehenge appears to have been the last gasp of this Stone Age culture, which was isolated from Europe and from the new technologies of metal tools and the wheel," Parker Pearson said.

Stonehenge's site may have been chosen because it was already significant to Stone-Age Britons, the researchers suggest. The natural land undulations at the site seem to form a line between the place where the sun rises on the summer solstice and where it sets in midwinter, they found. Neolithic people may have seen this as more than a coincidence, Parker Pearson said.

"This might explain why there are eight monuments in the Stonehenge area with solstitial alignments, a number unmatched anywhere else," he said. "Perhaps they saw this place as the center of the world."

Stonehenge is arguably one of the most famous megalithic monuments in the world. It's also one of the most mysterious, with its prehistoric concentric rings garnering plenty of speculation as to why and how they were constructed.

Megalithic Mysteries: Test Your Stonehenge Smarts

Theories and mystery

These days, Stonehenge is nothing if not the center of speculation and mystery. The monument has inspired its fair share of myths, including that the wizard Merlin transported the stones from Ireland and that UFOs use the circle as a landing site.

Archaeologists have built some theories on firmer ground. Stonehenge's astronomical alignments suggest that it may have been a place for sun worship, or an ancient calendar. A nearby ancient settlement, Durrington Walls, shows evidence of more pork consumption during the midwinter, suggesting that perhaps ancient people made pilgrimages to Stonehenge for the winter solstice, Parker Pearson and his colleagues have found.

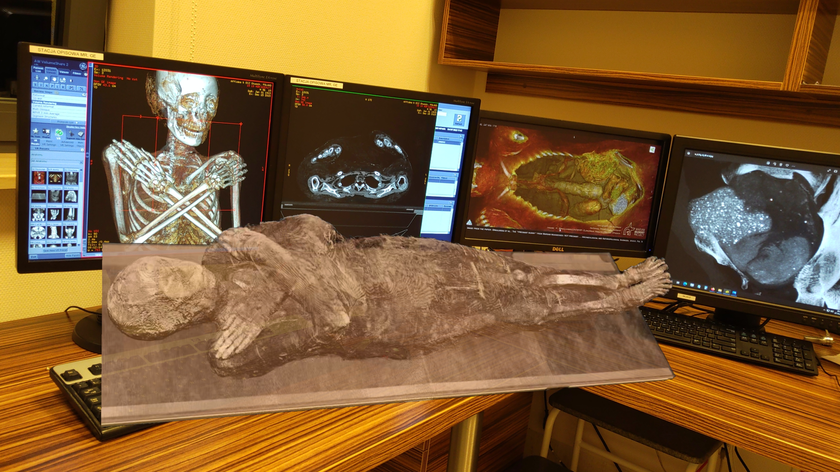

Stonehenge may have also been a burial ground, or a place of healing. Tombs and burials surround the site, and some skeletons found nearby hail from distant lands. For example, archaeologists reported in 2010 that they'd found the skeleton of a teenage boy wearing an amber necklace near Stonehenge. The boy died around 1550 B.C. An analysis of his teeth suggest he came from the Mediterranean. It's possible that ill or wounded people traveled to Stonehenge in search of healing, some archaeologists believe.

Other researchers have focused on the sounds of Stonehenge. The place seems to have "lecture-hall" acoustics, according to research released in May. One archaeologist even suggests that the setup of the stones was inspired by an acoustical effect in which two sounds from different sources seem to cancel each other out.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas or LiveScience @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.