Space Junk Hazards Force International Response

Time is running out to get serious about fixing the problem of space debris, experts say.

As more countries around the world build up their space capabilities, U.S. lawmakers are keen to address the growing issue of potentially harmful debris in orbit. But while policies have attempted to tackle the problem, no major strides have been made.

In 2010, the White House released its sweeping national space policy for the country, which identified orbital debris and the long-term sustainable use of space as clear priorities. But so far, few changes have been implemented on the ground or in space, said Brian Weeden, a technical adviser with the Secure World Foundation, an organization dedicated to the peaceful use of outer space.

"The policy is in place," Weeden, a former orbital analyst with the U.S. Air Force, told SPACE.com. "The language is there to indicate they see it as a significant problem, but at the moment, we don't see any follow-through in terms of actual plans and projects for how the U.S. government is going to address the problem of space debris."

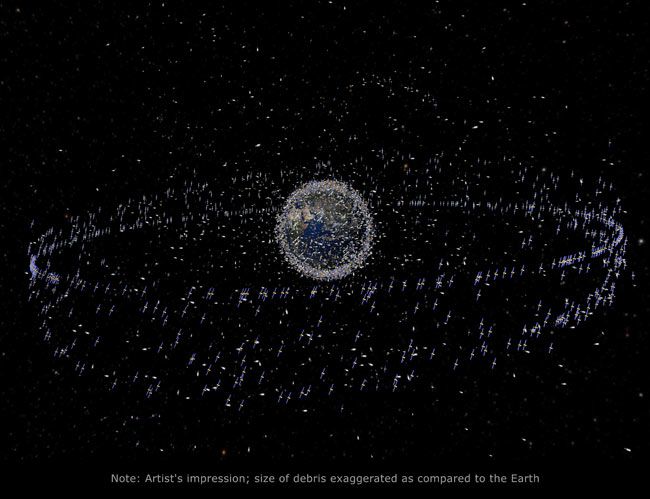

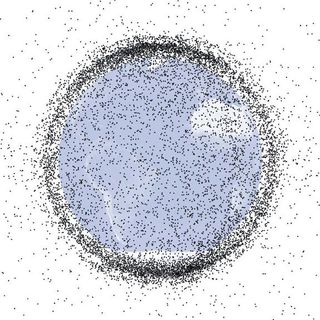

This is partly because experts are still working to understand the full extent of the issue. The U.S. military's Space Surveillance Network tracks roughly 22,000 pieces of orbital debris larger than 4 inches (10 centimeters), which include broken satellite parts and spent rocket bodies. The catalog is maintained by the United States Strategic Command, which falls under the domain of the U.S. Department of Defense.

"We do not currently have the capability to track debris smaller than 10 centimeters, but our estimate is that there are hundreds of thousands of pieces of debris that size and smaller that have the potential to do damage," said Frank Rose, deputy assistant secretary of state for space and defense policy. "We're at a tipping point — the debris problem has gotten substantially worse over the past five years." [Worst Space Debris Events of All Time]

Harmful space junk

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As these fragments zoom through space at 17,000 miles per hour (28,000 km per hour), they pose collision risks to the International Space Station, and the roughly 1,000 working satellites in orbit.

In February 2009, a U.S. Iridium 33 communications satellite crashed into a defunct Russian Cosmos 2251 military communications satellite. The smash-up destroyed the two spacecraft and created large clouds of pesky debris.

Earlier, in 2007, China intentionally destroyed one of its aging weather satellites in a controversial anti-satellite test that littered Earth orbit with more than 2,500 scraps of space junk.

"The Chinese ASAT (anti-satellite) test definitely had an impact because we're still seeing repercussions to this day," Weeden said. "For the foreseeable future, we'll have to maneuver satellites out of the way to avoid pieces of debris from that test."

As nations around the world continue to build up their space programs, and as societies become more dependent on satellites to provide communications and other crucial services, establishing guidelines for safe activity in space is imperative to avoid exacerbating the debris problem, said Lt. Col. April Cunningham, a spokesperson for the U.S. Department of Defense.

"As more countries and companies field space capabilities, it is in everyone's interest that they act responsibly and that the safety and sustainability of space is protected," Cunningham said. "A widely-subscribed International Code of Conduct for Outer Space Activities can encourage responsible space behavior, help to reduce the risk of debris, and increase transparency of space operations."

Such an agreement does not yet exist, but earlier this year, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton announced that the United States will work with other nations to develop an international code of conduct, so long as it does not conflict with the country's national security priorities.

An international problem

The European Union has been working on a voluntary code for several years, but U.S. officials have said they are not prepared to sign the E.U.'s draft legislation at this time. Rather, the U.S. government is using it as a stepping stone to the creation of rules that can be internationally agreed upon. Several experts are expected to gather this summer for the first multilateral meeting to discuss the development of a code.

"We believe that the E.U.'s draft is a good foundation for an international code, but there needs to be a more inclusive process," Rose said. "I think we are making progress — this is a good first step."

Rose said that most spacefaring nations have been open to discussions about the sustainable use of space, but some countries, including China, have been less receptive.

"We have not had robust discussions with our Chinese friends, but the U.S. very much wants to have an engagement with China on these issues," he explained. "It's in China's interest to maintain a safe and secure space environment because China is becoming more and more dependent on space systems as well." [Video: The Expanding Danger of Space Debris]

But getting various nations to agree on a set of regulations is not the only problem. Several agencies and private companies have submitted proposals for how to clean up space junk, ranging from robotic gas stations that could refuel aging satellites in orbit, to spacecraft that could collect and remove pieces of debris. But these schemes have raised thorny legal and political questions that experts are currently debating.

"I would say the primary challenges are political because it's a political process," Weeden said. "It requires coordinating input from all the major government agencies that will be involved, which is a major effort."

The way ahead

Still, working with other nations is critical, because the space environment is one that is shared globally.

"Responding to the challenges posed by space debris will require attention to a range of issues covering technology, cost, legal and policy requirements," Cunningham said. "The U.S. cannot do this alone. We will work through the United Nations, the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC), and in other fora to define and strengthen norms against the creation of new debris and to address the challenge of existing debris."

But this also requires lawmakers to understand the severity of the space debris issue. In today's challenging economic climate, and with so many other problems plaguing the nation and the world, understanding the value of space situational awareness can be tricky, Weeden said.

"In general, compared to the problems that the government is facing, it's a very little problem," he said. "But in regard to the ability to continue to use space in the future, for all the benefits we currently use it now, it's a very significant problem."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com staff writer Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.