In just six weeks, NASA's next Mars rover will attempt an unprecedented landing on the Red Planet that will have mission engineers on the edge of their seats with excitement and worry.

The 1-ton Curiosity rover — the centerpiece of NASA's $2.5 billion Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) mission — is due to touch down inside the Red Planet's Gale Crater on the night of Aug. 5. But it won't be easy.

"Entry, descent and landing, also known as EDL, is referred to as the 'seven minutes of terror,'" EDL engineer Tom Rivellini, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Pasadena, Calif., said in a recent JPL video.

"We've got literally seven minutes to go from the top of the atmosphere to the surface of Mars, going from 13,000 miles per hour to zero in perfect sequence, perfect choreography, perfect timing," Rivellini added. "And the computer has to do it all by itself, with no help from the ground. If any one thing doesn't work just right, it's game over."

'It looks crazy'

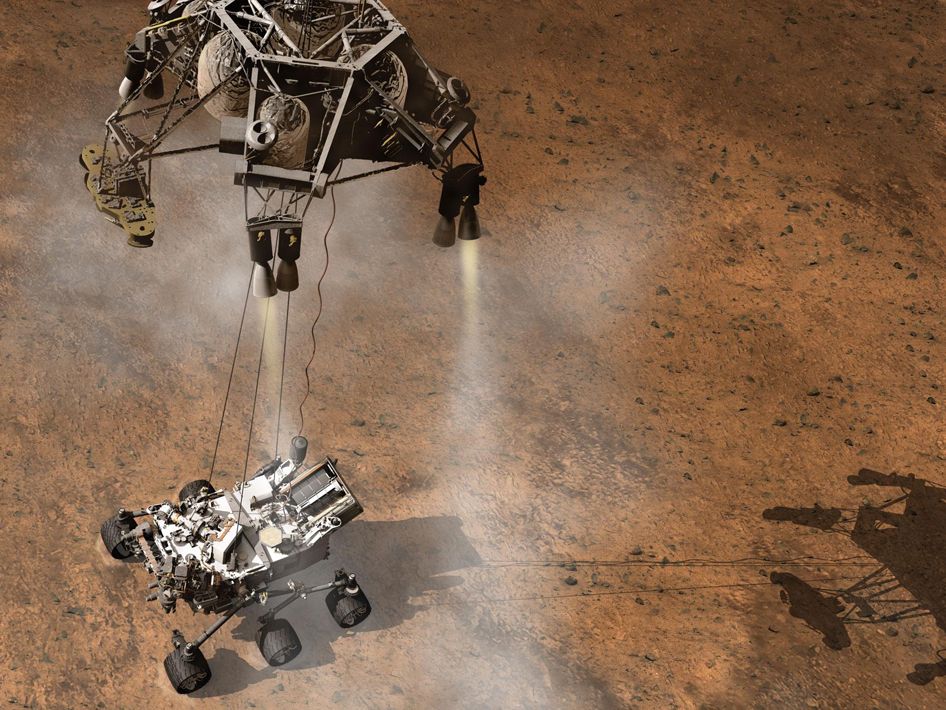

Curiosity's landing will likely be more anxiety-inducing than most planetary touchdowns. The robot is too big to land cushioned by airbags like previous Red Planet rovers, so researchers had to come up with an entirely new method.

They settled on a rocket-powered sky crane, which will lower Curiosity to the Martian surface on cables before flying off to crash-land on purpose a safe distance away. [Mars Rover's Sky Crane Landing (Infographic)]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"When people look at it, it looks crazy," EDL engineer Adam Steltzner, also of JPL, said in the video. "That's a very natural thing. Sometimes when we look at it, it looks crazy. It is the result of reasoned engineering thought, but it still looks crazy."

On the night of Aug. 5, the MSL spacecraft will hit the Martian atmosphere going about 13,000 mph (21,000 kph). As it barrels through the Red Planet air, MSL's heat shield will literally glow, reaching temperatures of about 2,900 degrees Fahrenheit (1,600 degrees Celsius).

The relatively thin Martian atmosphere will slow MSL down to only 1,000 mph (1,600 kph) or so, Rivellini said. So the spacecraft will also deploy a parachute, one that can withstand 65,000 pounds (29,500 kilograms) of force despite weighing just 100 pounds (45 kg) itself.

But even the parachute won't be enough.

"This big huge parachute that we've got, it'll only slow us down to about 200 miles per hour," Rivellini said. "And that's not slow enough to land. So we have no choice, but we've got to cut it off and then come down on rockets."

The rockets can't fire all the way to the ground, however, or they'd raise a huge dust cloud that could damage the rover's instruments and mechanisms, researchers said. To avoid such a ruckus, Curiosity will be lowered to the Martian surface on 21-foot-long (6.4 meters) cables. When the rover is safely down, the cables will be released and the rocket-propelled sky crane will fly off so it doesn't crash into Curiosity.

The 14-minute communications lag between Earth and Mars means that the MSL team won't be getting real-time updates about the rover's perilous journey.

"When we first get word that we've touched the top of the atmosphere, the vehicle has been alive, or dead, on the surface for at least seven minutes," Steltzner said.

Looking for habitable environments

Curiosity's main task is to determine if the Gale Crater area is, or ever was, capable of supporting microbial life.

The rover will explore the crater and Mount Sharp, a mysterious 3-mile-high (5 km) mountain rising from Gale's center. It will climb partway up Mount Sharp, examining the mound's various layers with 10 different science instruments, including a rock-zapping laser and gear that can identify organic compounds — the carbon-containing building blocks of life as we know it.

Curiosity's prime mission is slated to last one Martian year, which is slightly less than two Earth years. However, it may be able to go longer. NASA's Spirit and Opportunity Mars rovers, for example, far outlasted their 90-day warranties after landing in January 2004. Spirit was declared dead just last year, and Opportunity is still going strong.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter@michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also onFacebook and Google+.