Solar Tornadoes as Big as US Heat Sun's Atmosphere

For years, scientists have struggled to determine why the sun's atmosphere is more than 300 times hotter than its surface. But a new study has found a possible answer: giant super-tornadoes on the sun that may be injecting heat into the outer layers of our star.

While comparing images from the Swedish Solar Telescope with others taken by NASA's Solar Dynamics Observatory, an international team of scientists noticed bright points on the sun's surface and atmosphere that corresponded with swirls in the so-called chromospheres, a region that is sandwiched between the two layers. The finding indicates that the solar tornadoes stretched through all three layers of the sun.

The scientists went on to identify 14 solar super-tornadoes occurring within an hour of each other. By using a three dimensional simulation, the team then found that the swirls could play a role in elevating the sun's outer layer.

A sun 'super-tornado' is born

Unlike tornadoes on Earth, which are powered by differences in temperature and humidity, the twisters on the sun are a combination of hot flowing gas and tangled magnetic field lines, ultimately driven by nuclear reactions in the solar core. [How Sun Tornadoes Work (Infographic)]

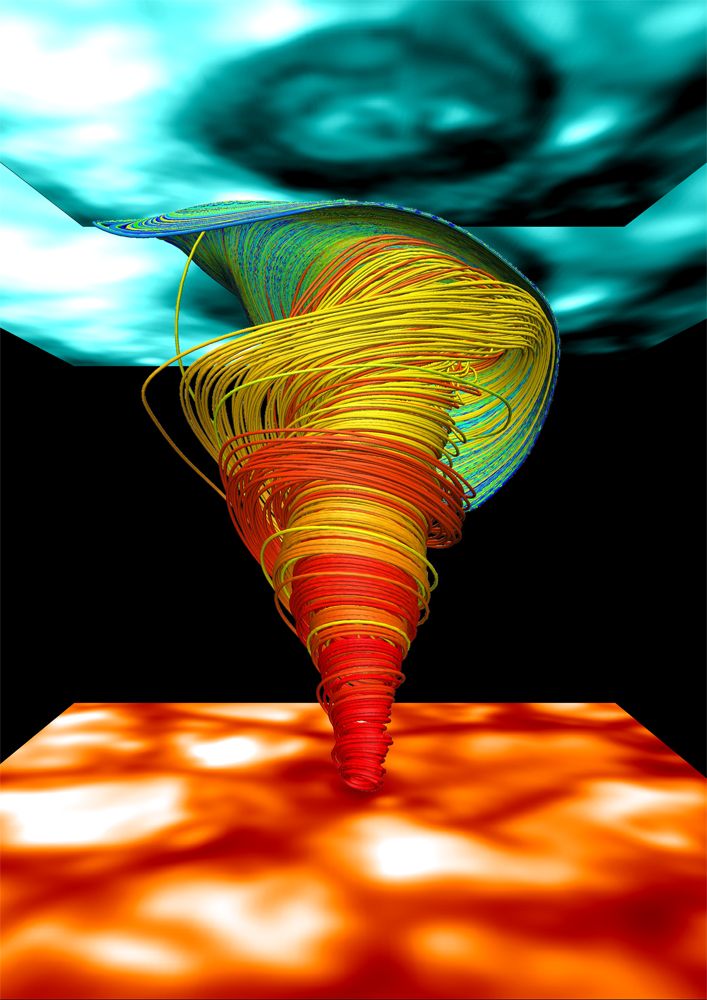

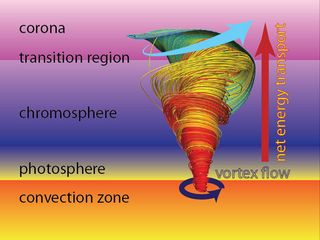

At the surface, or photosphere, cooled plasma sinks toward the interior like water running down the bathtub drain, creating vortexes that magnetic field lines are forced to follow. The lines stretch upward into the chromosphere, where they continue to spiral.

But while the hot gas at the surface drives the movement of the magnetic field, in the chromosphere it is the field lines that force the hot gas to spiral, creating the swirls that appear similar to tornadoes on Earth.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The resulting funnel is narrow at the bottom and widens with height in the atmosphere," lead scientist Sven Wedemeyer-Böhm, of the University of Oslo in Norway, told SPACE.com by email.

Spinning at thousands of miles per hour, the tornadoes vary in size, with diameters ranging from 930 to 3,500 miles (1,500 to 5,550 kilometers). Some of these giant solar twisters extend all the up in to the lower portion of the sun's upper atmosphere (called the corona, the researchers said.

"Based on the detected events, we estimate that at least 11,000 swirls are present on the sun at all times," Wedemeyer-Böhm said.

Towering solar twisters

Although the twisters are enormous by Earth's scale, they are tiny on the surface of the sun. They were first detected in 2008 by Wedemeyer-Böhm and another researcher, but it wasn't until images of super-tornadoes were compared with those from the corona and photosphere that scientists realized how high the writhing gas extended — or the influence they could have on the sun's temperature.

The surface temperature of the sun is 9,980 Fahrenheit (5,526 degrees Celsius or about 5,800 Kelvin), while the corona peaks at 3.5 million Fahrenheit (2 million degrees Celsius or nearly 2 million Kelvin), a fact that seems counterintuitive.

After observing the sun, the international team created computer models in an attempt to determine how much energy — and thus heat — could be effectively transported by the twisters. They concluded that solar tornadoes could help to explain how the outer layer stays so hot, although Wedemeyer-Böhm notes that it is likely only one of a number of different processes powering the temperature of the sun's corona.

"The magnetic tornadoes offer a potential, alternative and widespread way to transport energy from the solar surface into the corona," Wedemeyer-Böhm said.

The tornadoes differ from those spotted earlier this year. Those much larger events were formed by twisting solar prominences, and were likely connected to mass ejected from the sun. The smaller tornadoes are more abundant, and make a more significant contribution to the corona's temperature.

The research was published in today's (June 27) issue of the journal Nature.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.