Ancient Mars Water Existed Deep Underground

New evidence that water on Mars existed deep underground during the first billion years of the Red Planet's history has been found in rocks blasted out of Martian craters by ancient collisions, a new study finds.

Researchers using observations from the European Space Agency's Mars Express probe and NASA's Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) studied rocks on Mars that were ejected from impact craters. They found that underground water persisted deep below the planet's surface for prolonged periods during Mars' early existence.

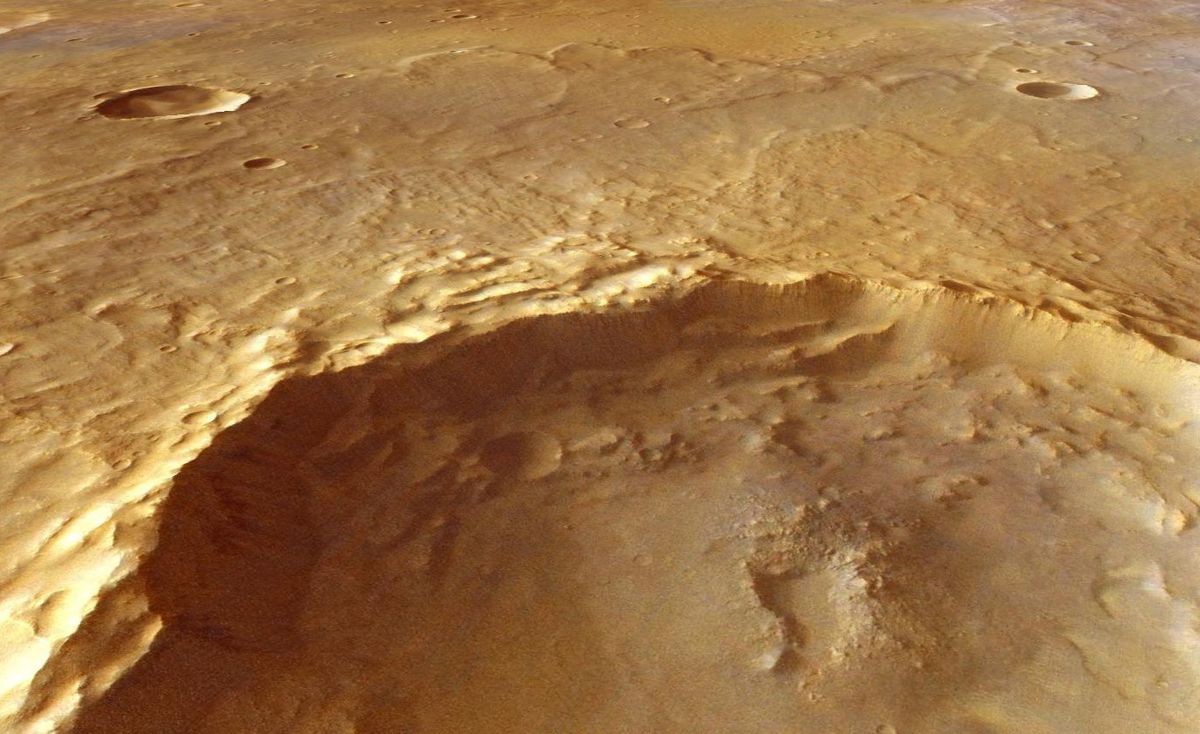

Astronomers can glimpse back into the history of a planet by studying impact craters, which act as natural recorders of the planetary surface. Essentially, deeper craters allow scientists to probe farther back in time, the researchers said.

Similarly, rocks that were ejected by these impacts offer the chance to study materials that once lay hidden beneath Mars' surface.

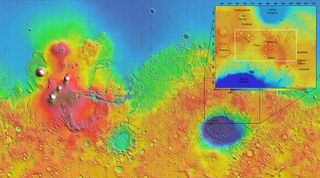

To explore Mars' geological past, astronomers used the Mars Express and MRO spacecraft to zoom in on craters in a 621-mile by 1,240-mile (1,000- by 2,000-kilometer) area, called Tyrrhena Terra, in the planet's southern highlands. [Photos: The Search for Water on Mars]

The scientists zeroed in on the chemistry of rocks embedded in the crater walls, rims and central uplifts, and also examined material surrounding the crater. They discovered 175 sites that contained minerals that are formed in the presence of water.

"The large range of crater sizes studied, from less than 1 km [0.62 miles] to 84 km [52 miles] wide, indicates that these hydrated silicates were excavated from depths of tens of meters to kilometers," study lead author Damien Loizeau said in a statement. "The composition of the rocks is such that underground water must have been present here for a long period of time in order to have altered their chemistry."

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The researchers found the minerals present in rocks that had been kicked up through impacts, but they did not see the same results with material on the surface between the craters in Tyrrhena Terra, which indicates the water existed deep underground.

"Water circulation occurred several kilometers deep in the crust some 3.7 billion years ago, before the majority of craters formed in this region," study co-author Nicolas Mangold said in a statement. "The water generated a diverse range of chemical changes in the rocks that reflected low temperatures near the surface to high temperatures at depth, but without a direct relationship to the surface conditions at that time."

But water on Mars has a varied history. For instance, Mawrth Vallis, one of the largest identified clay-rich regions on the Red Planet, exhibits a more uniform mineralogy pattern that indicates water was much more closely tied to surface processes on the planet.

The new results, however, add to astronomers' growing understanding of water on Mars, and could lead to clues of whether life exists, or ever existed, on the Red Planet.

"The role of liquid water on Mars is of great importance for its habitability and this study using Mars Express describes a very large zone where groundwater was present for a long time," said Olivier Witasse, a project scientist with ESA's Mars Express.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.