The ongoing brouhaha over arsenic-munching microbes on Earth shows just how tough it can be to search for "life as we don't know it" on our home world — and the challenges would be even greater on other planets.

On Sunday (July 8), two new studies threw further doubt on a bacterium's supposed ability to swap out phosphorus for arsenic in its basic molecular machinery. The microbe known as GFAJ-1 apparently does need phosphorus to survive, according to the new research, meaning it likely follows the same basic rules as all the other lifeforms we know about on our planet.

The uncertainty and controversy surrounding GFAJ-1 — whose discovery was announced in December 2010 — suggest that it would be tough for a robotic rover or lander, with its stripped-down instrument suite, to confirm the presence of life as we don't know it on another planet or moon.

Tough — but not impossible, if you cast a wide enough net, scientists say.

"You never know what you're looking for until you find it," said Seth Shostak, a senior astronomer at the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute in Mountain View, Calif. "About all you can say is, make as wide a variety of tests as you can afford to cram onto the spacecraft." [Extreme Life on Earth: 8 Bizarre Creatures]

Looking for life

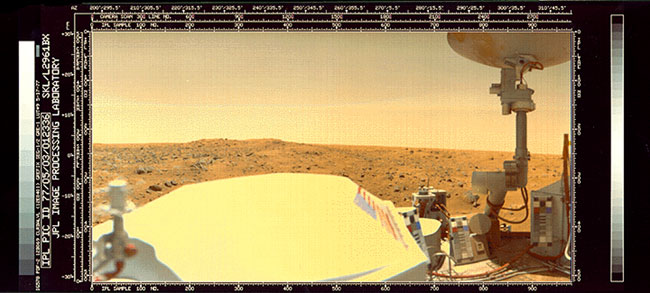

Searching for Earth-like alien life is a tough enough task, as the ambiguous results from NASA's Viking mission to Mars in the 1970s demonstrate.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But there's no guarantee that microbial life elsewhere in the solar system — if it exists — is Earth-like. Alien creatures may encode their genetic blueprints in a molecule other than DNA or RNA, for example. They may not even be carbon-based.

Standard biochemical techniques would have a hard time identifying such lifeforms in a scoop of Mars dirt or a thimbleful of ice from Jupiter's moon Europa. But other methods might have better luck.

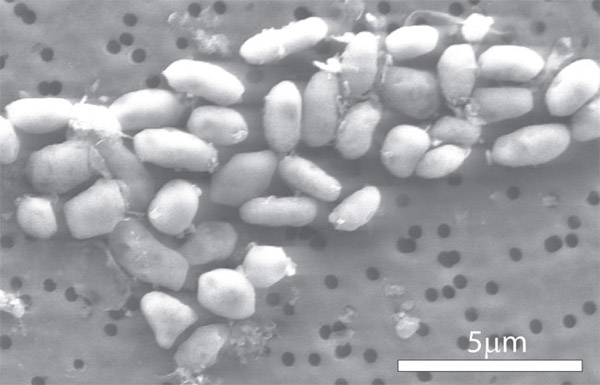

For instance, microscope observations could discover extraterrestrial organisms, regardless of their biochemical particulars.

A morphology-based identification would not necessarily be definitive; after all, scientists are still arguing over the possible "microfossils" spotted in the Mars meteorite ALH 84001 in the mid-1990s. But the potential is there.

"That falls under the rubric of what Justice Potter Stewart said about pornography — you'll know it when you see it," Shostak told SPACE.com, referring to a famous 1964 Supreme Court case that considered whether obscenity is protected under the First Amendment.

Left-handed life?

Another possible tactic, Shostak said, is to zero in on molecules' chirality, or handedness.

Complex molecules often come in two different mirror-image forms, a left-handed version and a right-handed version. Here on Earth, biomolecules tend to be one of these versions, but not the other. For example, life utilizes only left-handed amino acids for protein synthesis.

So finding a trove of complex molecules on another world that are exclusively right-handed or left-handed — or "homochiral" — could be a strong indicator of life, the thinking goes.

Confirming the discovery of alien microbes that are fundamentally different than Earth organisms would probably require a multitude of tests and a variety of evidence, Shostak said. And in the end, it may come down to Justice Stewart's "know it when you see it" test.

"You think of all the properties you think that biology would exhibit — it grows, and it needs an energy source, and it moves around a little bit and it's maybe got a cell wall," Shostak said. "You do all these tests, and what does the evidence say to you — guilty or not guilty? Most science isn't done by that sort of vote. But that's probably what it's going to come down to inevitably, unless it's very, very obvious."

Discovering intelligent extraterrestrial life, on the other hand, would probably be a bit more clear-cut.

"When you're looking for advanced lifeforms, I think you've got a much easier job," said Shostak, who is doing just that at the SETI Institute, searching for signals from alien civilizations. "I mean, if you see an interstate highway system, it's not as ambiguous as finding things that sort of look like a microbe but might not be."

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.