Talking Apes Project Faces Cash Crisis

A group of endangered apes uses special keyboards to talk with humans at a scientific facility in Iowa. Their unusual skill is raising broad questions about language and learning, but a funding crisis threatens to shut down the unique experiment.

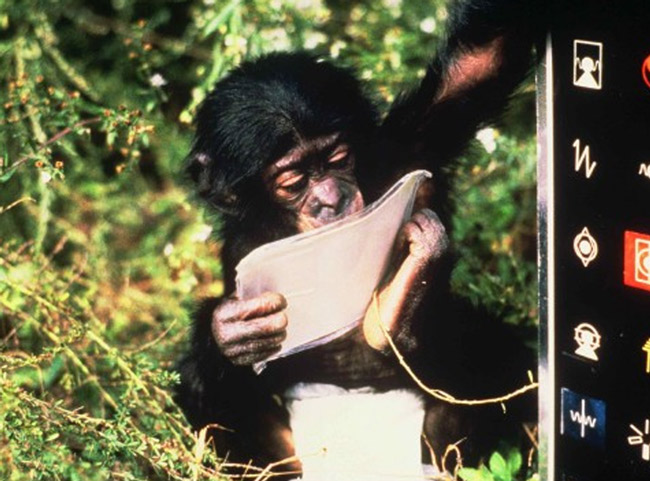

One bonobo chimpanzee named Kanzi rose to stardom when he began spontaneously "talking" as a baby — he had watched a researcher try (unsuccessfully) to teach his mother the lexigram symbols representing certain words. The talking skills of Kanzi and his half-sister Panbanisha have since drawn the attention of Oprah Winfrey and Anderson Cooper and earned worldwide fame for the Great Ape Trust in Des Moines.

"We're pretty much the lone bastion for this kind of language research," said Kenneth Schweller, board chairman of the Great Ape Trust. "We all agree that the bonobos can communicate what they want, ask questions, and make clear what they want to do."

The trained individuals among the three generations of bonobos can point to the lexigram symbols on their keyboards to talk about the foods they're eating (Ape translation for pizza: bread-cheese-tomato) or ask visitors questions. They're also big fans of Skype video chats .

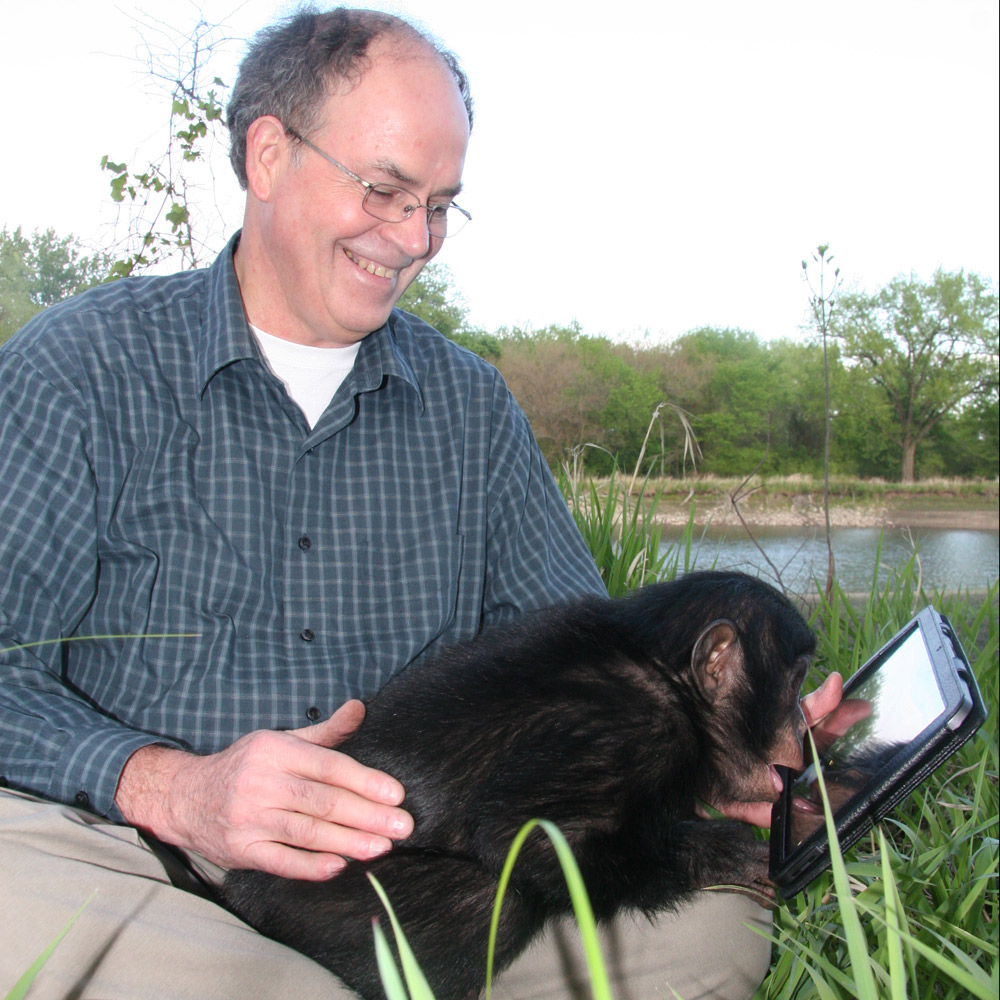

Schweller now has hopes for creating special language apps on tablets for the apes.

But the trust faces a struggle for survival in the next several months. The facility's founder, Ted Townsend, had privately sponsored the trust, but his endowment of $4 million a year shrank during the recession to barely half a million, and Townsend finally told the trust he had no more money to give.

Why talking apes matter

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The bonobos' ability to carry on two-way conversations with humans stands out in the animal world, said Heidi Lyn, a cognitive psychologist at the University of Southern Mississippi.

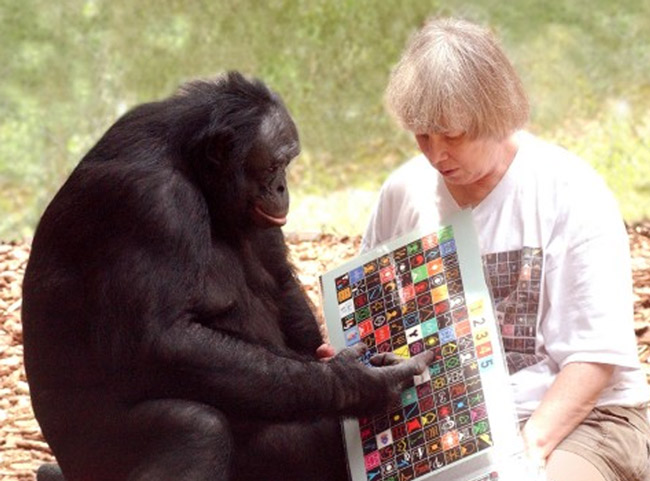

Past studies tried teaching sign language to chimps, gorillas and orangutans, but researchers debated whether the apes were truly communicating or simply imitating. Much uncertainty finally fell away when Sue Savage-Rumbaugh began her work with the bonobos. Savage-Rumbaugh, executive director and senior scientist of the Great Ape Trust, carried out rigorous experiments to show that the bonobos could clearly talk by pointing to the lexigram symbols on their keyboards to form phrases or sentences.

"One question for the sign language research was whether people were over-interpreting apes' gestures," Lyn told InnovationNewsDaily. "In this case, the keyboard pointing was super-clear."

There were no forced experiments; Savage-Rumbaugh and her colleagues had to make the learning both voluntary and fun for the bonobos. The apes learned their lexigram symbols in a social, nurturing environment with their human caretakers.

That nurturing environment has boosted the apes' thinking capabilities beyond just communication, Lyn said — the bonobos performed better on spatial abilities and counting tasks than did apes raised in conditions similar to zoos or biomedical labs. More study could possibly help researchers better understand the impact of learning on not only apes, but on humans such as kids with autism. [Humans' Ancient Brains Can Forge the Future ]

"We know the Great Ape Trust apes can do declarative information sharing, but we don't know why," Lyn said. "That kind of information sharing is exactly what autistic kids don't do. But if we can find out why the apes learned to do it, there could be applications for humans."

Hooked on tablets

Funding problems have put some projects on hold.

The bonobos at the Great Ape Trust could get new high-tech tools to boost their language learning. A third-generation son of Kanzi, named Teco, already has become accustomed to the touch interface of tablets — a more intuitive technology that may eventually replace the need for the apes to point at individual lexigrams on their keyboards. An "autocomplete" or "autofill" option on the tablet also could speed up communication.

"Saying something like a long sequence of words on the keyboards is really time-consuming," Lyn explained. "One thing we know about communication is that it's super-fast. When you slow it down, people don't want to say a five-word sentence."

Similarly, Schweller envisions language-learning apps on tablets for the apes — his outside job title is professor of computer science and psychology at Buena Vista University in Storm Lake, Iowa. One of Schweller's students built an app that would display lexigram symbols doing somersaults, speak the English words loudly, and play music whenever an ape touched a relevant object in room.

The bonobos could use their wireless keyboards and apps someday even to open doors or windows, access food vending machines, control cameras, or possibly alert security guards about suspicious activity or intruders near their compound, Schweller wrote in IEEE Spectrum .

Schweller previously tried to attract donations through Kickstarter to build a "Robo-Bonobo" and bonobo chat app that would allow the apes to safety interact with outsiders. He says he may try again after getting advice from kind strangers about why his Kickstarter project failed to hit its fundraising goal.

Publicity problems

Scrambling to find new funding has not been the only problem for the trust. Disagreements between Savage-Rumbaugh and William Fields, former lab director of the Great Ape Trust, over management and caretaking issues led in December 2011 to public accusations and counteraccusations alleging lab misconduct and animal abuse .

These troubles occurred during a time when Savage-Rumbaugh had been taking care of baby Teco around the clock. (Teco's mother required the help of Savage-Rumbaugh and the other female bonobos when Teco would not cling to her.) Fields eventually resigned as lab director, and a new board of directors headed by Schweller brought Savage-Rumbaugh back on board as chief scientist.

(Lyn agreed to serve as interim director for the Great Ape Trust during this period, until she needed to return to her own work.) Since then, Schweller has focused on trying to get the trust back on a solid financial footing so that he can return to developing high-tech tools for talking to the apes.

"We've had to put a lot of program development on hold and concentrate on fundraising because of the need to raise enough money to stay in Des Moines," Schweller said. "But I'm a computer programmer at heart. I look forward to getting back to that as my main job."

This story was provided by InnovationNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow InnovationNewsDaily Senior Writer Jeremy Hsu on Twitter @ScienceHsu. Follow InnovationNewsDaily on Twitter @News_Innovation, or on Facebook.