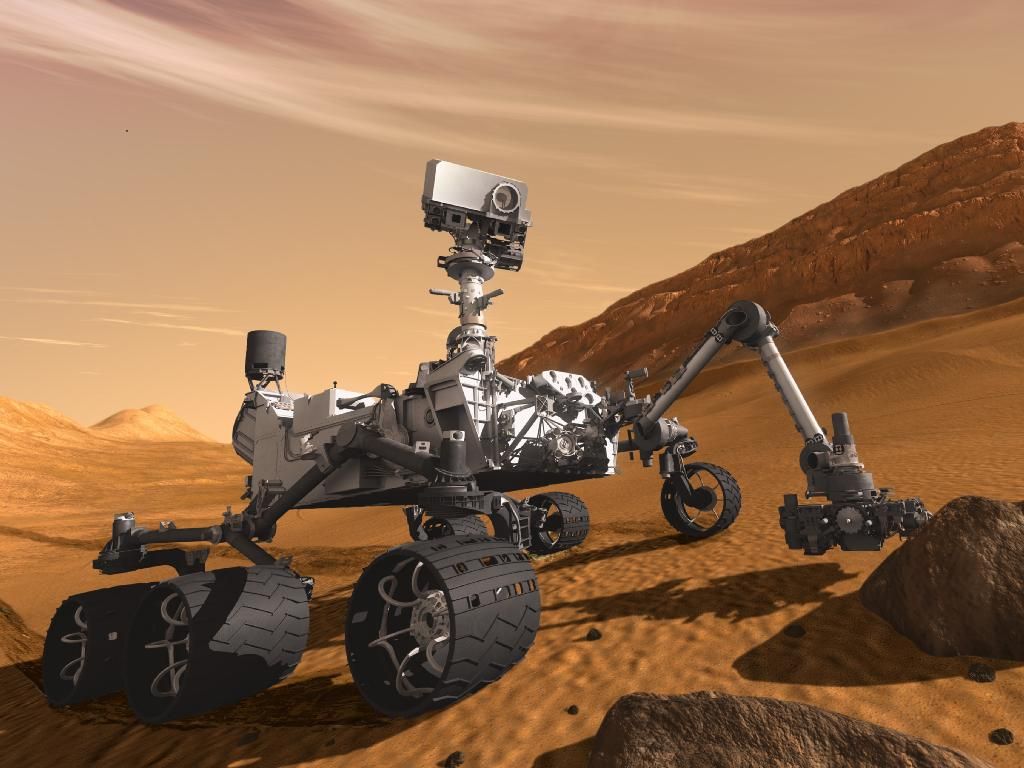

Despite NASA's tough budget situation, the 1-ton rover streaking toward an Aug. 5 landing on Mars is unlikely to be the space agency's last big, ambitious Red Planet mission.

Funding cuts have forced NASA to shelve plans for future multibillion-dollar "flagship" planetary missions beyond the $2.5 billion Curiosity rover, which will investigate Mars' potential to host past or present microbial life after it touches down three weeks from now. For the time being, the space agency is looking for ways to explore the Red Planet on the cheap.

But over the long haul, NASA still has its sights set on a particularly alluring flagship — a sample-return effort that would bring pieces of Mars back to Earth for study.

"The scientific goal — and for human exploration as well — of a Mars sample-return is still the highest priority in the long term," John Grunsfeld, NASA's associate administrator for science, said in April. [7 Biggest Mysteries of Mars]

Tough budget times

President Barack Obama's federal budget request for 2013, which was unveiled in February, keeps NASA's overall budget flat, at $17.7 billion.

But the request cuts NASA's planetary science funding from $1.5 billion to $1.2 billion, with further reductions expected in coming years. The space agency's Mars program gets hit particularly hard, with funding dropping from $587 million this year to $360 million in 2013, then falling to just $189 million in 2015.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As a result, NASA is scaling back and reformulating its Red Planet exploration strategy. The space agency has put together a committee called the Mars Program Planning Group, which is assessing possible future missions to Mars.

NASA also withdrew from the European-led ExoMars mission, which aims to launch an orbiter and a rover to the Red Planet in 2016 and 2018, respectively.

ExoMars is viewed as a key step toward sample-return, which the U.S. National Research Council identified last year as the highest-priority planetary science mission for the next decade.

Many researchers believe that sending pieces of the Red Planet back to Earth is the best way to search for signs of Martian life. But sample-return would almost certainly be a multibillion-dollar flagship effort, putting it out of NASA's reach in today's budget environment.

"There is no room in the current budget proposal from the president for new flagship missions anywhere," Grunsfeld said shortly after the budget was released. [NASA's 2013 Budget: What Will It Buy?]

Still aiming for sample-return

NASA has one more Mars exploration effort firmly on the docket beyond Curiosity, a $485 million orbiter called Maven (short for Mars Atmosphere and Volatile EvolutioN), which is due to launch in late 2013 to study Mars' upper atmosphere.

The space agency also plans to launch another mission in either 2018 or 2020, to take advantage of a favorable Mars-Earth alignment and to keep the Red Planet program moving forward. This effort, which will likely cost less than $800 million, remains largely undefined, with rovers and orbiters still under consideration, officials have said.

But in the long run, NASA remains committed to sample-return, and it continues to hold out hope that an improved fiscal situation will make it possible someday.

Mars exploration is, after all, a stated priority of the Obama Administration. In 2010, the president directed NASA to work toward getting astronauts to the vicinity of Mars by the mid-2030s. And before sending humans to the Red Planet, we should really determine if the world harbors life of its own, NASA officials have said.

"If Mars already has life, you have to understand the effects on humans," McCuistion said. "So this is a critical question — not just the innate human question of 'Are we alone?' but also safety of humans on the surface of the planet," Doug McCuistion, director of the Mars Exploration Program at NASA Headquarters in Washington, D.C., said in April.

Mars is too compelling to ignore

While the outlook for big-ticket NASA Mars missions such as sample-return may be bleak right now, the agency should get its shot someday, experts say. The Red Planet is simply too inviting to resist over the long haul.

"Mars is such a compelling scientific target," said Scott Hubbard of Stanford University, the former "Mars Czar" who restructured NASA's Red Planet program after it suffered several high-profile failures in the late 1990s.

"You can get to it every 26 months, and it's the place in the solar system most likely to have had life emerge," Hubbard told SPACE.com. "If you add that to Mars being also the most logical ultimate target for human exploration, I think that Mars will continue to be part of the space exploration portfolio."

But Hubbard — who just published a book about his Mars Czar days ("Exploring Mars: Chronicles from a Decade of Discovery") — added that it's in the United States' best interest to give NASA the means to tackle ambitious Mars missions sooner rather than later. The nation risks losing its space and technological supremacy if it allows other countries to achieve feats like sample-return first, he said.

Curiosity could help NASA carve out a bolder future at Mars, Hubbard said. If the huge rover performs as advertised, it could generate excitement among the American public and, perhaps, the politicians who hold NASA's purse strings.

"I've seen the pendulum swing back and forth, and I hope that the successful mission will push it back in the direction of Mars exploration," Hubbard said.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.