Heat Wave Builds Again — When Will It Go Away?

Okay, we get it — it's hot. But why? And when will it cool down?

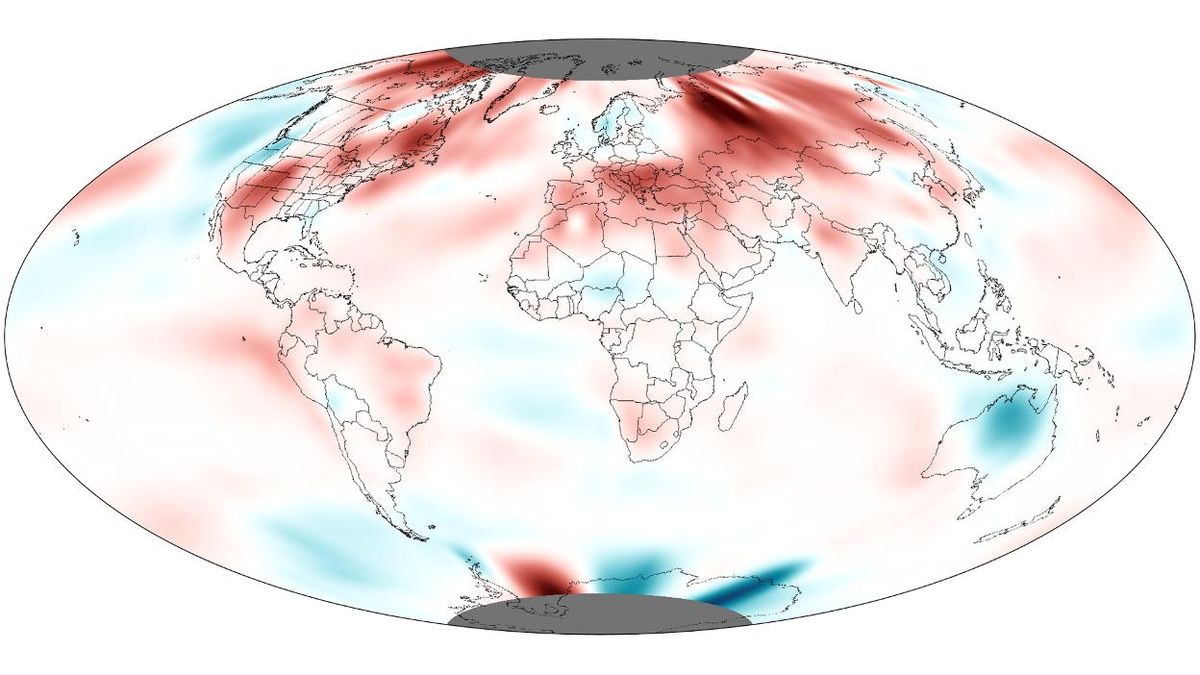

The heat started in earnest last month, which the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration just declared to be the warmest June ever on record in the Northern Hemisphere since record-keeping began in 1880.

The baking heat has continued into July. Already this month, 155 all-time high temperatures have been recorded throughout the United States, according to government records; only 12 records were set in the first half of July last year.

Last week, there was some relief, with temperatures "dipping" to around average; but now, it's getting hotter than usual again. It's all part of a pattern that will likely repeat itself for the rest of the summer, said Jeff Weber, a scientist with the University Corporation for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colo.

Same song, second verse

It goes like this: Rising heat generates a high pressure system in the Southwest and Great Plains that slowly rolls across the country, causinguncomfortably high temperatures in any given area for about 10 days. Then a lower pressure system moves through, providing some mild relief for about three to four days, which happened last week. Then, another heat wave comes again — as is happening now, Weber said. And so on. [Harshest Environments on Earth]

The epicenter for heat this year will be in the area surrounding Missouri, including Illinois and Arkansas, Weber told OurAmazingPlanet.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This heat comes from a persistent mass of hot air over the central part of the country called a heat dome. The system is unfortunately stuck in place, said Jake Crouch, a climate scientist with the National Climatic Data Center. That's because of a slowdown of the North Atlantic Oscillation, a climate pattern that pulls weather patterns eastward across the country.

This "blocking" of the Atlantic has caused the jet stream, which normally ferries air from west to east across the United States, to buckle and trap heat in the middle and eastern parts of the country, Weber told OurAmazingPlanet.

That's not unusual in the summer, said National Weather Service meteorologist Greg Carbin. But this pattern of hot air does cover a broader area than usual, and the total amount of hot air is greater, stretching higher up in the atmosphere than normal, he said.

The drought makes the heat worse, since all the energy from the sun's rays goes into warming the Earth's surface. Wet soils use up heat when water evaporates. "The heat amplifies the drought, but the drought amplifies the heat," Crouch said.

Currently more than half the United States is in a drought, making it one of the worst dry spells in the last half century.

The heat dome doesn't look likely to completely dislodge itself for the remainder of the summer, and above-average temperatures are expected throughout the central and eastern parts of the country (excluding the northeastern states of Vermont, New Hampshire and Maine), Carbin said.

Climate change connection

The heat waves of summer — following higher temperatures in spring and winter — could also be part of a pattern of climate change.

"It's consistent with what we'd expect in a warming climate, but it's hard to quantify any effect climate change might have on an individual event like this heat wave," Crouch said.

While only one heat wave cannot by itself be linked to climate change, a significant increase in these types of events over time could be a hallmark of a warming planet. "An increasing frequency of heat waves —that's one aspect of climate change you can point to," Carbin said.

While the United States bakes, much of Europe has seen heavy rains. These contrasting patterns are connected, Weber explained. The heat dome over the U.S. causes weather systems to go around them, and not drop rain. But much of Europe is in a trough, where storms gravitate. "There's a moisture budget," he said. "When you're not getting moisture some place, you must be getting it somewhere else."

The Southwest, Colorado and surrounding areas have gotten a fair amount of relief in the past week from the return of the North American monsoon, although this won't help most of the central area of the country and the East Coast. There could be some relief for the Southeast and Southwest in the fall if an El Niño develops, climatologists say; the system is linked to higher-than-average rainfall in these areas. But El Niño may not help the northern United States, where it's associated with drier, warmer winters.

Reach Douglas Main at dmain@techmedianetwork.com. Follow him on Twitter @Douglas_Main. Follow OurAmazingPlanet on Twitter @OAPlanet. We're also on Facebook and Google+.