Earth's Hot Formation May Solve Water Shortage Mystery

Earth probably formed in a hotter, drier part of the solar system than previously thought, which could explain our planet's puzzling shortage of water, a new study reports.

Our newly forming solar system's "snow line" — the zone beyond which icy compounds could condense 4.5 billion years ago — was actually much farther away from the sun than prevailing theory predicts, according to the study.

"Unlike the standard accretion-disk model, the snow line in our analysis never migrates inside Earth's orbit," co-author Mario Livio, of the Space Telescope Science Institute (STScI) in Baltimore, said in a statement.

"Instead, it remains farther from the sun than the orbit of Earth, which explains why our Earth is a dry planet," Livio added. "In fact, our model predicts that the other innermost planets — Mercury, Venus and Mars— are also relatively dry. " [A Photo Tour of the Planets]

Earth a dry planet?

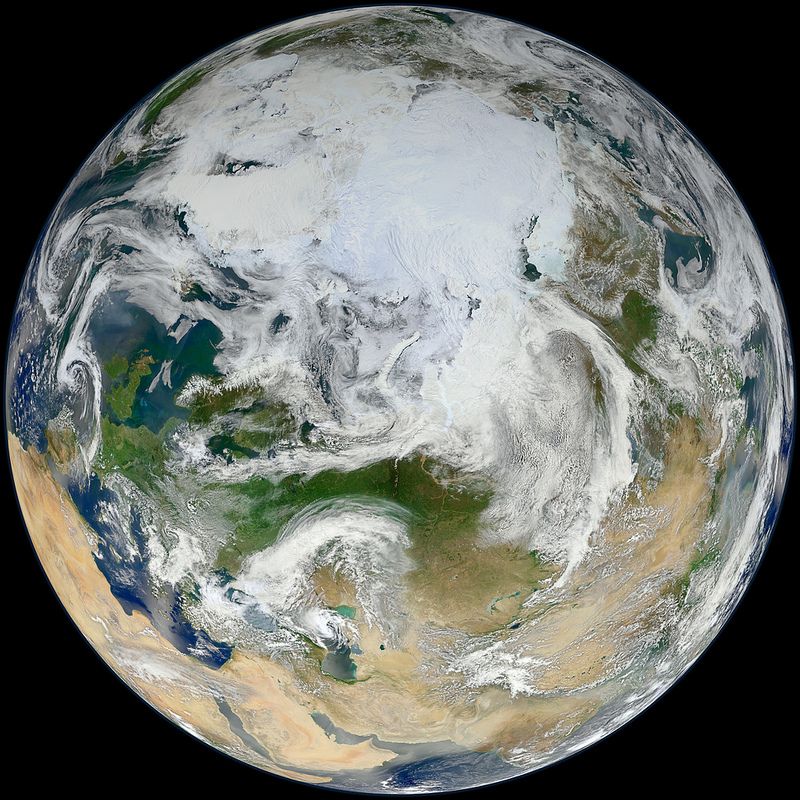

Referring to Earth — with its vast oceans, huge rivers and polar ice caps — as a dry planet may sound strange. But water makes up less than 1 percent of our planet's mass, and much of that material was likely delivered by comets and asteroids after Earth's formation.

Scientists have long been puzzled by our planet's relative water deficiency, especially because Earth is thought to have coalesced from water-rich substances out beyond the snow line.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The snow line now lies in the middle of the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter, but conventional models suggest that it was much closer to the sun 4.5 billion years ago, when Earth and the other planets took shape.

"If the snow line was inside Earth's orbit when our planet formed, then it should have been an icy body," said co-author Rebecca Martin, also of STScI. "Planets such as Uranus and Neptune that formed beyond the snow line are composed of tens of percents of water. But Earth doesn't have much water, and that has always been a puzzle."

The new study, which has been accepted for publication in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, may help solve the mystery.

Moving the snow line

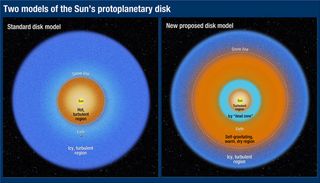

In the prevailing model of how things happened 4.5 billion years ago, the protoplanetary disk around our newborn sun was fully ionized — meaning electrons in the region had been stripped off their parent atoms by powerful solar radiation.

Material from the disk fell onto the sun, the theory goes, heating the disk up. Initially, the snow line was far away from our star, perhaps 1 billion miles (1.6 billion kilometers) or more. (Earth orbits the sun at a distance of 93 million miles, or 150 million km.)

But over time, according to the model, the protoplentary disk ran out of material and cooled. As a result, the snow line moved inward, past Earth's orbit, before our planet had a chance to form.

But Martin and Livio found some potential problems with this scenario. Specifically, they say that protoplanetary disks around young stars aren't fully ionized.

"Very hot objects such as white dwarfs and X-ray sources release enough energy to ionize their accretion disks," Martin said. "But young stars don't have enough radiation or enough infalling material to provide the necessary energetic punch to ionize the disks."

A dead zone in the disk

If our solar system's disk wasn't ionized, its material would not have been funneled onto the young sun's surface, researchers said. Instead, gas and dust would simply have orbited around our star without moving inward, creating a so-called "dead zone" in the disk.

This dead zone would have acted as a plug, blocking matter from migrating toward the sun. Gas and dust would have piled up in the dead zone, increasing its density and causing it to heat up by gravitational compression.

This process, in turn, would have heated up the area outside the plug, vaporizing icy material and turning it into dry matter. Earth formed in this hotter region, whose dry matter became the building blocks of our planet, according to the new study.

While this new model could explain Earth's relative lack of water, it shouldn't be extended to all newly forming planetary systems, researchers said.

"Conditions within the disk will vary from star to star, and chance, as much as anything else, determined the precise end results for our Earth," Livio said.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.