'Evil' Plankton Even More Deadly

Plankton species Alexandrium tamarenseis is known to unleash neurotoxins that are harmful to humans, fish, birds and other large organisms. But new research found the algae is also equipped with a second toxin that destroys tiny, one-celled predators.

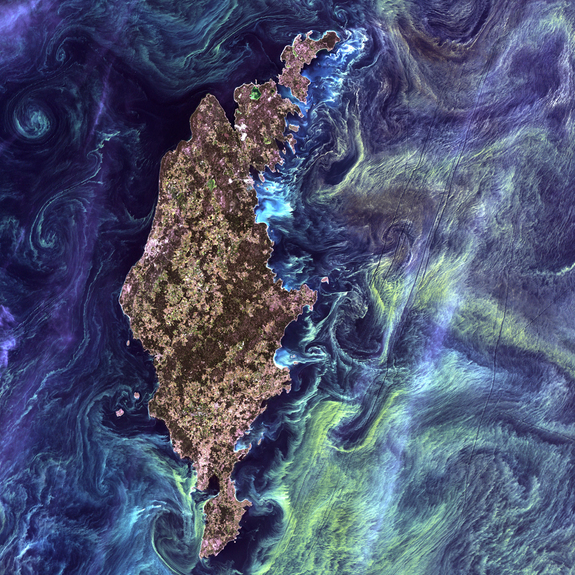

Alexandrium is a prominent contributor to toxic algae blooms, sometimes called “red tides” for the way they discolor the water. The species is toxic to large organisms with a central nervous system and it has been blamed for marine animal deaths and some human deaths, via contaminated shellfish.

Researchers recently noticed that Alexandrium was also having a strange effect on its one-celled predators. Those predator organisms were getting sick and dying when in the vicinity of Alexandrium.

Hans Dam, with the University of Connecticut, and his team showed in laboratory experiments that Alexandrium produces another toxin, called a reactive oxygen species, which attacks those tiny predators by bursting their cell membrane, according to a statement.

"If you only have one cell, lysing [breaking down] your cell membrane is all it takes to kill you," Dam said. "This new mechanism of toxicity, combined with the other, is pretty evil."

Dam explained that Alexandrium’s two-pronged toxic defense could have implications for entire marine food chains.

"These small predators that are being affected by the reactive oxygen species are the things that typically eat large amounts of the algae and keep them from growing like crazy," Dam said. "This brings up a whole new line of inquiry for us: What will actually control these algae in the future?"

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

His team will next try to understand how the species produces this second toxin and whether it has an effect on multi-cellular animals, according to a release from the University of Connecticut.

Dam is also investigating how the algae may affect commercial species, such as salmon and king crab, with researchers at the University of Los Lagos in Chile.