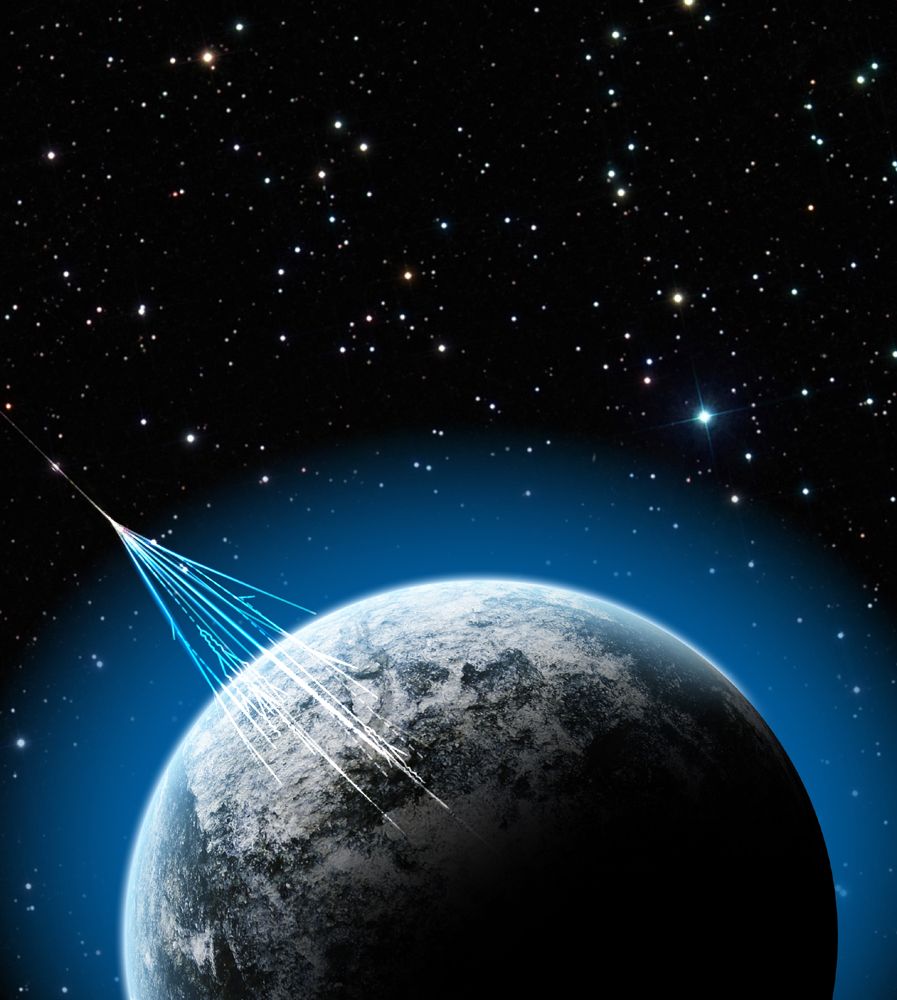

Cosmic Rays Still Mysterious 100 Years After Discovery

Cosmic rays continue to puzzle scientists a century after the fast-moving particles were discovered.

Austrian scientist Victor Hess first cottoned on to the existence of cosmic rays after a high-altitude balloon flight on Aug. 7, 1912. In the 100 years since, researchers have learned a lot about these highly energetic particles, which constantly bombard Earth from outer space. But important questions remain, including where exactly they come from.

Scientists got on the trail of cosmic rays in the 1780s, when French physicist Charles-Augustin de Coulomb noticed that an electrically charged sphere spontaneously lost its charge. This seemed strange, because at the time scientists believed air to be an insulator rather than a conductor.

Further experiments demonstrated, however, that air becomes a conductor when its molecules are ionized — given a net positive or negative electrical charge — by interaction with charged particles or X-rays. [Video: Monster Stars Spit Cosmic Rays]

The source of these particles baffled scientists, as experiments showed that objects were losing their charge even when shielded by large chunks of lead, which blocks X-rays and other radioactive sources.

That's where Hess' landmark 1912 balloon flight comes in. At an altitude of 17,400 feet (5,300 meters), he measured ionizing radiation levels about three times greater than those seen on the ground. Hess concluded that this radiation is penetrating Earth's atmosphere from outer space, an insight that earned him the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1936.

Hess had discovered cosmic rays, charged subatomic particles that streak through space at nearly the speed of light. They're thought to be atomic nuclei from the entire range of naturally occurring elements, though the vast majority appear to be protons (hydrogen nuclei).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The source of cosmic rays, however, has remained mysterious. Scientists aren't sure which cosmic phenomena are accelerating the particles to their fantastic speeds.

"The universe is full of natural particle accelerators, as for example in supernova explosions, in binary star systems or in active galactic nuclei," said Christian Stegmann, head of the German Electron Synchrotron research center (known by its German acronym, DESY) at Zeuthen, in a statement.

"So far, only 150 of these objects are known to us, and we have just an initial physical understanding of these fascinating systems," Stegmann added.

DESY is helping to organize a symposium to mark the 100th anniversary of the discovery of cosmic rays. From Aug. 6-8, scientists from around the world will meet in Bad Saarow in the German state of Brandenburg, where Hess landed his balloon a century ago. They'll present and discuss the latest research about the ultra-speedy particles — including ideas about how to unlock their long-held secrets.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Most Popular