Touching Mars: Huge NASA Rover Carries Strong Arm for Red Planet

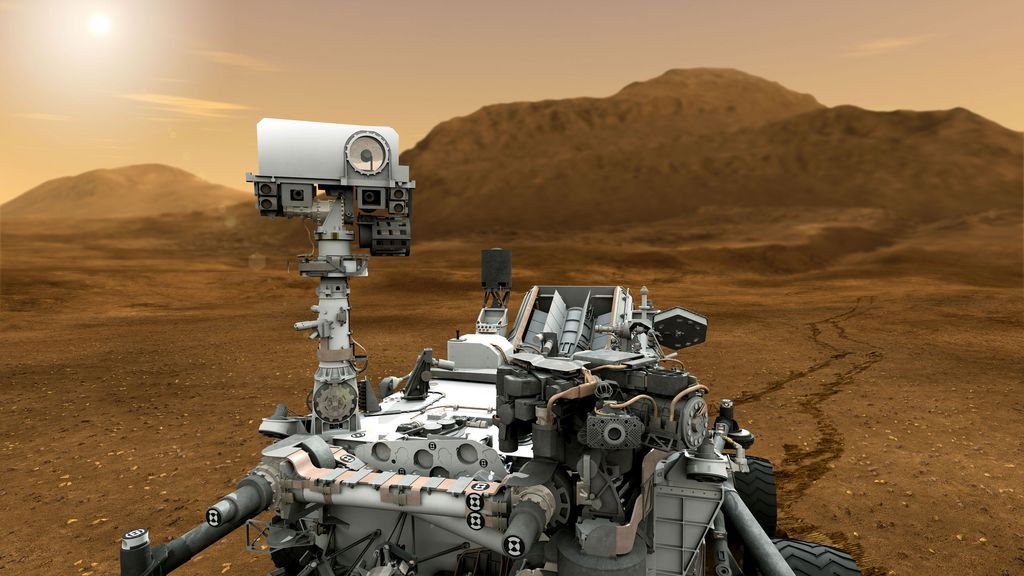

NASA's next Mars rover, which is cruising toward an Aug. 5 landing, is a whole new breed of Red Planet explorer. You can tell just by looking at its huge and powerful robotic arm.

The 1-ton Curiosity rover, which is the centerpiece of the $2.5-billion Mars Science Laboratory (MSL) mission, is the size of a Mini Cooper. Its arm is longer than most people are tall, clocking in at 7 feet (2.1 meters).

A bulky toolkit at the end of the arm will allow Curiosity to study and manipulate Martian rocks and soil like no previous rover. One of the tools is a drill that can go 1 inch (2.5 centimeters) deep, enabling the rover to access the interior of Red Planet rocks.

“It’s an important and amazing engineering feat,” said Ashwin Vasavada, MSL's deputy project scientist. “We have this huge seven-foot arm with 75 pounds of tools at the end of it, and yet we have to place it out in front of us within millimeters to enable the science team to do their work. We want [to touch] that particular black mineral, or that particular rock layer.”[Curiosity Armed with Laser, Cameras (Infographic)]

Curiosity's main goal is to determine if its landing site, the 96-mile-wide (154 kilometers) Gale Crater, can or ever could host microbial life. The arm hosts tools both old and new to aid in this quest.

The venerable Alpha Particle X-Ray Spectrometer (APXS) — which was used on the previous Mars rovers Sojourner, Spirit and Opportunity — will return on Curiosity with even better sensitivity, more schedule flexibility and better control.

Contributed by the Canadian Space Agency, the instrument bombards samples with alpha particles and X-rays and measures the energy of the X-rays that bounce back.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

APXS will help scientists determine what minerals each sample is made of. Typical rocks on Mars include the elements of oxygen, silicon, aluminium, iron and calcium, Vasavada said.

If water previously touched the rock, APXS could see elements such as sulphur, zinc, bromine, chlorine or phosphorus.

“You can tell how much a rock or soil has been altered or weathered," Vasavada said. "A pristine rock could be distinguished from one that has seen water on its surface.”

He added, “In the context of the mound within Gale Crater, we’ll be looking for how these quantities change with each layer, essentially with time. From that, we’ll piece together how the regional and/or planetary environment conditions changed over Mars’ early history, and implications for habitability.”

Another one of Curiosity’s arm instruments is the Mars Hand Lens Imager (MAHLI), which is essentially a 2-megapixel off-the-shelf digital imager that has macro capabilities. The purpose, said Vasavada, is to look at rocks closely enough to see grains.

“It allows us to get 10 to 15 pixels (of resolution) across every single grain. Then you can talk about the shape and color of it,” he said.

“In the example of sand — which isn’t the primary goal of the mission — but if you look at a sand grain, it has sharp corners if it just freshly broke of a rock yesterday and hasn’t seen much action," Vasavada added. "But if you look at sand on a beach that has been hit by waves, the grains are all rounded.”

Curiosity’s 10 science instruments (some of which are located on the arm, some inside and some on the rover) have a mass of about 165 pounds when taken together. That's about 15 times the mass of the five instruments Spirit and Opportunity each carried to the Red Planet when they landed in 2004.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Elizabeth Howell @howellspace, or SPACE.com @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.