Organism Lives 10 Times as Long After Genetic Tinkering

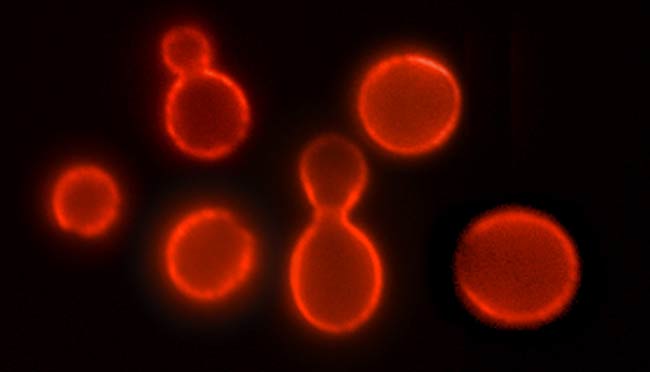

Scientists have extended the lifespan of yeast, microbes responsible for creating bread and beer, by 10-fold. That's twice the previous record for life extension in an organism.

The breakthrough could ultimately inform efforts to extend human lives.

Instead of one week, the yeast lived for about 10 weeks through genetic tinkering and a low-calorie diet.

"We've reprogrammed the healthy life of an organism," said Valter Longo, a biologist at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles who led the life-prolonging experiments.

Longo and his colleagues detail their findings in two upcoming studies; one in the Jan. 25 issue of the journal PLoS Genetics and another in the Jan. 14 issue of the Journal of Cell Biology.

Genetic soldiers

DNA, short for deoxyribonucleic acid, is the body's set of blueprints and instructions, carried by genes.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Evolution designed our genes, our army, to be ready for growth and reproduction," Longo told LiveScience. Problem is, pooling the body's efforts into growing makes room for genetic errors that lead to age-related disease. "We can use our energy to grow and reproduce, or protect ourselves."

Longo and his team previously found two genes — RAS2 and SCH9 — related to growth and development of cancer that are similar in humans and yeast. They are so alike, in fact, that Longo said, "you can put the human gene in yeast and it works."

The scientists disabled the genes in the yeast but also put the organism on a low-calorie diet. Caloric restriction has prolonged the lifespan of yeast, worms, and mice in other experiments, and is thought to work by scaring the body into maintaining its genetic goods instead of growing.

Combining both age-fighting approaches, Longo said, led to a dramatically long lease on life.

"We expected a small boost in longevity, but not a 10-fold increase," he said. "It's remarkable."

Longo thinks the genes act like generals of the genetic army, ordering the troops to protect the body's DNA under caloric stress instead of fighting for growth.

“I would say 10-fold is pretty significant,” said Anna McCormick, chief of the genetics and cell biology branch at the National Institute on Aging in Bethesda, Md, of Longo's findings.

Hope for humans?

To find out how the age-defying treatment works in humans, Longo and his group are now studying Ecuadorians who have similar mutations in age-controlling genes used in the yeast.

“People with two copies of the mutations have very small stature and other defects,” he said.

Despite the problems, Longo said, the people likely benefit from their condition.

"So far, we have never seen cancer in people who have two copies of the mutated genes," he said. “We are now identifying the relatives with only one copy of the mutation, who are apparently normal. We hope that they will show a reduced incidence of diseases and an extended life span.”

Longo thinks life-extending drugs that have no major side effects will not be easy to develop but should be possible in the future. He explained that manipulating the genes leads to major growth defects probably because they are inactive during childhood.

"What if we could achieve a balance by switching those genes off when we want to?" he asked. "Twenty or thirty years from now, we might have the ability to reduce the activity of [the genes]. In the long run, I think that balance may not be too hard to achieve."