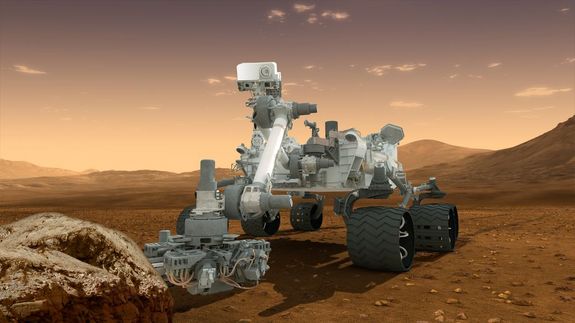

What If the Curiosity Rover Finds Life on Mars?

In this weekly series, Life's Little Mysteries provides expert answers to challenging questions.

If all goes as planned, NASA's Curiosity rover will touch down on Mars late Sunday night. Then, after a few weeks' respite, it will begin probing the subsurface soils looking for organic molecules that could be the detritus of ancient Martian life.

A few billion years ago, vast oceans might have sloshed over the surface of the Red Planet, and a thick atmosphere probably enshrouded it. The liquids and gases have all but burned away by now, but any organisms Mars harbored in its ancient glory days would have left behind traces in the form of large, carbon-based molecules. "Organic molecules can last for billions of years," explained Alexander Pavlov, a planetary scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center.

Any simple organic matter Curiosity digs up could have biological origins, but it could also have been generated through more mundane chemical processes. However, if the rover detects complex organic structures — the kind we find in living things, and practically nowhere else but Earth — these would be "a very strong indicator" of ancient life on Mars, Pavlov told Life's Little Mysteries.

As Seth Shostak, senior scientist at the SETI Institute, put it, "It would be like finding 2-ton blocks of limestone in the desert in Egypt and saying, hmm, these might be leftover pieces of a structure around here somewhere."

Such a discovery would confirm for the first time that life has existed elsewhere in the universe. Big news, for sure — but what would life on Mars really mean for life here on Earth? [7 Theories on the Origin of Life]

Ethnically Martian

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

If life exists on Mars, then we might be ethnic Martians ourselves, scientists told Life's Little Mysteries. They explained that the small coincidence of having two life-bearing planets right next door to one another gets cleared up if one of the planets actually seeded life on the other — a concept called "panspermia." According to Pavlov, hundreds of thousands of Martian meteorites are strewn across Earth. These were hurled into space during past planetary collisions (such as the bash that left Mars with a crater covering nearly half its surface). One of these chunks of Mars could feasibly have contained spores that lay dormant during the interplanetary commute to Earth, and then blossomed upon arrival, some 3.8 billion years ago.

Alternatively, any Martian microbes we find could be ethnic Earthlings that made the trip from here to there. That's a little less likely, considering the relative locations and gravitational pulls of the planets, the scientists said.

Either way, we can tell if Martians and Earthlings have a common root by determining whether Martian life encodes itself the same way we do — with DNA. DNA breaks down on hundred-thousand-year time scales, so we would need to find living or freshly dead alien microbes in order to be sure that Mars' life arose independently of Earth's. Pavlov says it's very possible that living things are eeking out an existence in Mars' inhospitable modern landscape, if they were ever there in the first place. As attested to by the extremophiles inhabiting Earth's underground volcanoes and frozen tundras, life tends to adapt and persist once it gets started. Following this line of thinking, if Curiosity finds remains of ancient life, NASA's next Mars mission will go in search of extant microorganisms.

But if all the Martians we find are long dead, we might never know whether they were our cousins or not. It makes all the difference, in terms of understanding our place in the cosmos. If life arose just once, then the possibility remains that it could be exceedingly rare in the universe, Pavlov said. But if it arose twice in the same solar system, "then that would tell us that life is extremely common." [If We Discover Aliens, What's Our Protocol for Making Contact?]

Not alone

As for how the discovery of Martian microbes would impact the average human, "we've done this experiment before," Shostak said. In 1996, the headline on the front page of the New York Times exclaimed, "Clues in Meteorite Seem to Show Signs of Life on Mars Long Ago," after NASA scientists incorrectly concluded that they had found microscopic fossils in a meteorite denoted ALH84001, which originated on Mars.

So, how did people react to the news?

"The public was very interested, but I can't say there was a sudden outbreak of world peace, or people rioting in the streets," Shostak said. "I don't think it would change day-to-day behavior. The long-term consequences are a little less predictable, because it affects religious belief if Earth isn't all that special."

At the very least, alien life would resurrect the evolution versus creationism debate, said Jacob Haqq-Misra, a research scientist with the Blue Marble Space Institute of Science, a nonprofit research institute. If Martian microbes contain DNA, a telltale sign that they're our ancestors, Christian fundamentalists' sentiment that we're far too special to have descended from monkeys might be repurposed toward denying the possibility of our descent from Martian microbes. "The philosophical and religious implications of microbial life are easy to ignore, because the discovery of microbes does not necessarily imply that human beings are any more or less rare," said Haqq-Misra, an astrobiologist formerly at Penn State.

We're not going to find intelligent, communicative beings on the Red Planet. So, ultimately, although Martian microbes have big implications for scientists and philosophers, Haqq-Misra said the rest of the world will sooner or later "lose interest."

This story was provided by Life's Little Mysteries, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow Natalie Wolchover on Twitter @nattyover or Life's Little Mysteries @llmysteries. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Natalie Wolchover was a staff writer for Live Science from 2010 to 2012 and is currently a senior physics writer and editor for Quanta Magazine. She holds a bachelor's degree in physics from Tufts University and has studied physics at the University of California, Berkeley. Along with the staff of Quanta, Wolchover won the 2022 Pulitzer Prize for explanatory writing for her work on the building of the James Webb Space Telescope. Her work has also appeared in the The Best American Science and Nature Writing and The Best Writing on Mathematics, Nature, The New Yorker and Popular Science. She was the 2016 winner of the Evert Clark/Seth Payne Award, an annual prize for young science journalists, as well as the winner of the 2017 Science Communication Award for the American Institute of Physics.