Why We're Obsessed with Mars

It's easy to forget there was life believed to be on Mars 60 years ago.

Before the Mariner flybys in the 1960s, scientists thought Mars had water and life, even if it was just some sort of plantlike lichen.

"Mars' spectrum, its color in the near infrared, mimics that of vegetation. Back in the '50s and '60s, they concluded that was evidence of chlorophyll, and Mars had vegetation," said Josh Bandfield, a Mars expert and planetary scientist at the University of Washington.

And if there were plants believed to be living on the planet, well, it wasn't so far-fetched to invent invading aliens in pop culture, whether they were evil mind controllers ("Invaders from Mars") or goofy intruders with peculiar genetic defects ("Mars Needs Women"). Thanks to NASA, which has yet to find life on Mars, in present day it's humans who brave space, landing on a lifeless desert. From pulp fiction to literary thrillers, changing scientific knowledge of Mars has influenced the planet's place in art.

For scientists, dreams of life on Mars persist: When the Curiosity rover lands Sunday, Aug. 5, at 10:30 p.m. PDT (1:30 a.m. EDT, 0530 GMT),it will try to determine if Mars could support microbial life. [Full Coverage: Mars Curiosity Landing]

But absent little green men, what drives our culture's fascination with Mars?

Mars' mystique

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"There was just enough of a possibility that Mars might be able to support an intelligent population that made it fascinating for masses of people," said Bob Crossley, emeritus professor of English at the University of Massachusetts in Boston and author of the book "Imagining Mars: A Literary History" (Wesleyan, 2011).

Yet Crossley, who is old enough to remember the era of Mars life, said there is more to the planet's mystique. "Somewhere deep in my own psyche, and maybe for other people as well, there is a desire for another world," he said. "For me, the deepest meaning of Mars is it represents some kind of longing for something outside ourselves, something outside our own world."

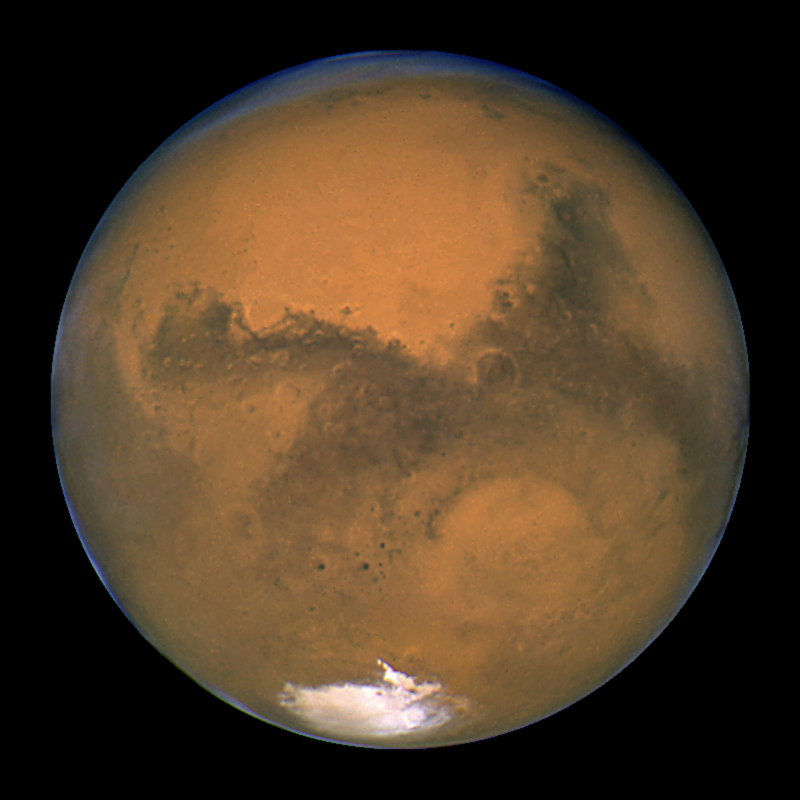

As one of our closest and most familiar neighbors, the Red Planet has served as the source of legends since the first storytellers slept under the stars. With its 24.6-hour day and snowy polar caps, Mars is really the only place that looks promising for life — whether alien or an outpost for humans. In modern times, that makes it a perfect slate for allegories about human behavior, from the recently deceased sci-fi author and space visionary Ray Bradbury's critiques of American culture to Kim Stanley Robinson's sci-fi books on the ecological and sociological sustainability on Mars. [5 Mars Myths & Misconceptions]

Our interest in the past century has waxed and waned with the planet's proximity to Earth, said Bill Sheehan, a psychiatrist, amateur astronomer and author of the book "Mars: The Lure of the Red Planet" (Prometheus Books, 2001).

A close approach in 1956 coincided with fears of communism. During the 1950s, America was swept up in anti-communist paranoia provoked by Sen. Joseph McCarthy and the House Committee on Un-American Activities. "The increasing interest in Mars, and the general state of anxiety, almost panic, for the communist threat, was really the perfect recipe for an episode of alien hysteria," said Sheehan.

On the big screen and in books, because Mars was still thought to hold vegetal life, the planet was an unparalled source of evil scary monsters, ushering in some of the best and worst alien movies of the 1950s and 1960s. But writers such as Bradbury, who were critical of government policies, also commented via stories set on Mars. "It worked both ways, as a form of propaganda and cultural criticism," said Crossley.

Even though the 1964 film "Santa Claus Conquers the Martians" might have been best left in the can, the volume of books and films produced during this era ensured Mars entered the public consciousness and never left.

Wax and wane

"The nature of people's interest in Mars has evolved in the last 50 or 60 years, but it's never entirely vanished," said Crossley.

In the 1960s, the early Mariner missions prompted a radical change in our relationship with Mars, when images showed an apparently dead, cratered planet.

"The flyby showed pictures of a very moonlike landscape, which had a staggering effect," said Sheehan. "It left people quite demoralized." NASA's expeditions may have killed some of the Red Planet's romanticism, Sheehan believes.

"The less defined an object is like Mars, the more evocative it is. We use it as a Rorschach to project our hopes and fears on to. As Mars becomes more explored, it becomes a more quotidian setting that no longer captures the imagination," Sheehan said.

After the Mariner missions, it took years before Mars again became a destination for humans in popular culture. These days, authors must tread carefully with reams of scientific data available for consumers who are feeling contradictory.

"Mars in popular culture today is in inseparable from the science of Mars," said Crossley.

Sheehan notes that big-screen farces like "Mars Attacks" and "Total Recall" may go down easily, but attempts to accurately recreate the Red Planet seem to bomb at the box office. Take "John Carter," a movie detailing what happens when a Civil War veteran is transplanted to the Red Planet: "That was one of the most disastrous movies of last summer," said Sheehan.

Nowadays, how does a movie producer (or NASA) drum up excitement about Mars when a teenager can virtually drive a rover across its rocky red dust?

For Erika Harnett, a space physicist who grew up on sci-fi stories, it’s the tantalizing feeling that the reality of Mars is within reach.

"We understand Mars to a degree that we have not even come close to on any other planets or moons. I think what gets a lot of scientists excited is no different than what gets the public excited: the idea of when can we send people there, can we find life on Mars," said Harnett, a professor at the University of Washington.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.